By Veronica A. Arntz

The Church as a Liturgical

Community:

Ecclesiological Problems with

Communion for the Divorced and Remarried

As the drama of Communion for the

divorced and remarried continues to unfold, especially with the recent papal

letter to the Argentinian bishops, Robert Royal made a stunning yet accurate

remark in his recent article,

“A Bizarre Papal Move”: “Indeed, Catholics have a new teaching now, not only on

divorce and remarriage. We have a new vision of the Eucharist.” If we say that

certain individuals who are divorced and remarried, and thus living in an

adulterous union, can receive Communion, then we have indeed changed our

understanding of the Eucharist. No longer is it a matter of discerning the Body

and Blood of our Lord (see 1 Corinthians 11:27-29), but rather, the Eucharist

becomes “a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak” (Evangelii

Gaudium, art. 47).

Rather than recognizing our

infinite failings and sins and refraining from receiving the Lord, if the

condition of our soul necessitates such an action, the Eucharist has now become

a mere remedy for anyone who would wish to receive him. This offense to the

Precious Body and Blood of our Lord would be enough to lead us to condemnation.

However, this change in our perception of the Eucharist extends to how we

understand the Church—thus, in changing the way we approach the Eucharist, we inevitably

change the nature of the Church as a whole.

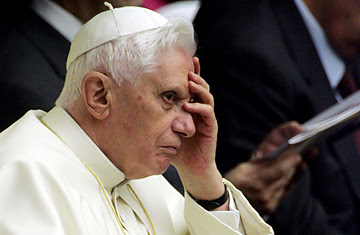

Among the first to discuss the

nature of the Church as communio,

Henri de Lubac recognized the problem with an individualistic understanding of

the sacraments. (NB: While we cannot praise de Lubac for his modernistic

tendencies, it seems that he was at least aware of the problems of

individualism in the Church). In Principles

of Catholic Theology (Ignatius Press, 1987), Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

writes of de Lubac’s view: “The concept of a Christianity concerned only with my soul, in which I see only my justification before God, my saving grace, my entrance into heaven, is for de Lubac that caricature of

Christianity that, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, made possible the

rise of atheism” (p. 49). Thus, it is incorrect to understand Christianity in

an individualistic way; we cannot understand the faith as the means only for my

salvation—this is reminiscent of a Protestant perspective.

If the Church is merely about my

own salvation, then there is no real sense of community and no real sense of

all individuals on a journey toward the Heavenly Jerusalem. Ratzinger

continues, extending de Lubac’s thought to the sacraments: “The concept of

sacraments as the means of a grace that I receive like a supernatural medicine

in order, as it were, to ensure only my own private eternal health is the supreme misunderstanding of what a

sacrament truly is” (Ibid). Thus, if we understand Christianity in

individualistic terms, we likewise apply that same construction to the

sacraments—the sacraments themselves become the means by which I obtain my salvation, and my salvation alone.

While there is a certain truth to that, de Lubac and Ratzinger are speaking about

a superficial understanding that has crept into the Church. Participating in a

sacrament only for the purposes of receiving personal salvation reveals a false

understanding of the nature of a sacrament and thereby the Church.

We can perhaps understand this

concept more clearly in light of the current situation with the divorced and

remarried, and even the misunderstanding of the Eucharist presented by Pope

Francis in Evangelii Gaudium (cited

above). The Eucharist is the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, and we only ought to

receive him if we find that we are worthy of him, meaning that we are in a

state of grace. Generally, Catholics are too willing to receive the

Eucharist—how often does a whole parish line up to receive Christ, yet most do

not even understand his Real Presence in the Eucharist? All of us ought to

consider more carefully whether we have been attentive enough to his Presence

before we proceed to receive him so automatically. Therefore, if we make the

allowance for certain divorced and remarried individuals to receive the

Eucharist for this or that reason—their situation is complicated, they really

love each other, they have five children together, etc.—are we not saying that

the Eucharist is an individualistic sacrament? Are we not saying that the

Eucharist is meant for “personal salvation” (although in the cases of the

divorced and remarried it could lead to damnation)? If we admit the divorced

and remarried to Communion, we are essentially saying that the Eucharist is an

individualistic sacrament, meant to redeem each individual personally, because

each individual’s situation is different and cannot be placed within moralistic

constraints (Amoris Laetitia, art.

298).

Nevertheless, Ratzinger helps us

to see that the sacraments are not meant merely for personal salvation. Because

sacraments are signs, directing us toward eternal life in Christ, he writes, “A

holy sign, in other words, requires liturgical action, and liturgical action

requires a community in which to exist and which embodies the fullness of power

for such liturgical action” (p. 48). Thus, the sacraments are liturgical

actions that must occur within a community, a community ultimately oriented

toward Christ. We can see how this is true even for the sacrament of Baptism,

which is an individual’s entrance into the Church and necessary for that

individual’s salvation. The Baptism of that individual, however, affects the

whole community—the parents of that child are required to raise him or her in

the faith, and the rest of the community is to assist the parents in that

mission. As Ratzinger explains

in his Letter to the Bishops of the

Catholic Church on Some Aspects of the Church Understood as Communion:

Every member of the

faithful, through faith and Baptism, is inserted into the only, holy, catholic,

and apostolic Church. He or she does not belong to the universal Church in a mediate way, through belonging to a particular Church, but in an immediate way, even though entry into

and life within the universal Church are necessarily brought about in a particular Church (art. 10).

Thus, even the sacrament of

Baptism initiates the individual into the community of the whole Church—no

sacrament can be considered the means of individual

salvation. In this way, Ratzinger considers the Church herself to be a

sacrament, as he explains in Principles

of Catholic Theology, “We can say, then, that the seven sacraments are

unthinkable and impossible without the one sacrament that is the Church; they

are understandable at all only as practical realizations of what the Church is

such and as a whole” (p. 48).

Ratzinger gives us three principles

that help us to understand the Church as sacrament, and ultimately, the Church

as communio, which will in turn help

us to understand further why the divorced and remarried (who have not repented)

cannot receive Communion. First, as we have already been discussing, the

designation of the Church as a sacrament as opposed to an individualistic

understanding of the sacraments “teaches us to understand the sacraments as the

fulfillment of the life of the Church” (p. 50). Furthermore, in teaching us

about the life of grace as the “beginning of union,” it shows that, “as a

liturgical event, a sacrament is always the work of a community” (Ibid). Once

again, the sacraments are not meant to be individualistic means of

salvation—they are meant to be the work of the community toward eternal

salvation. This may perhaps explain why Rogier van der Weyden’s Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (1445-1450)

depicts all seven sacraments occurring simultaneously within a Gothic

cathedral: the sacraments are oriented toward the liturgical action of the

Church community, not in an anthropocentric way, but in a way that emphasizes

the communal nature of the Body of Christ (see Romans 12:5).

Speaking specifically to our

current situation within the Church, if certain individuals who are unworthy,

such as the divorced and remarried, proceed to receive the Eucharist, they are

not the only ones who are affected negatively but also the entire community

with which they are participating in the Eucharist.

Ratzinger’s second principle

stems from the first: “The Church is not merely an external society of

believers; by her nature, she is a liturgical community; she is most truly

Church when she celebrates the Eucharist and makes present the redemptive love

of Jesus Christ” (Ibid). (NB: I have also spoken here

about the Church as a liturgical community). Unlike in a Protestant church,

where there is nothing substantial to unite the believers who attend the

church—each believer appears to be an autonomous member and only experiences

the church community through participation in human activities—the faithful of

the Catholic Church are united by

something substantial. Indeed, they are united by the Substance, the substance of the Body and Blood of Christ.

The baptized believers of the

Catholic Church, therefore, reveal their identity by celebrating the sacrament

of the Eucharist—this truly defines the Catholic Church. Thus, the community of

the Church is defined by its liturgical activity, and because the members of

this community are not juxtaposed with each other, there must be a unified

action in celebrating the Eucharist. As Ratzinger explains in Feast of Faith (Ignatius Press, 1986):

“For community to exist, there must be some common expression; but, lest this expression by merely external, there

must be also a common movement of internalization,

a shared path inward (and upward)” (p. 69). Therefore, if certain members of

that liturgical community are not oriented toward the same goal, which is union

in Christ, then there is division within that community. The common expression

of the community no longer exists if the Eucharist is turned toward an

individualistic interpretation. While certain individuals may always receive

the Body and Blood of Christ without the proper disposition, those who are

divorced and remarried are living in public

sin, and therefore have an even greater potential for scandalizing the

community.

Ratzinger expands the first two

principles in his third and final principle: “The positive element common to

both of these statements is to be found in the concept of unio and unitas: union

with God is the content of grace, but such a union has as its consequence the

unity of men with one another” (p. 50-51). The ultimate reason for receiving

any sacrament, but especially for receiving the sacrament of the Eucharist, is

for being open to union with God. This union with God, as we have already seen,

leads to union with the community. This is the meaning of the Body of Christ,

for even though we are all individual members, all are necessary for the Body

to function and be healthy; the actions of one affect the others (see 1

Corinthians 12:12-31. Note that this passage follows immediately after St.

Paul’s exhortation about receiving the Eucharist worthily). If we deny union

with God by receiving the sacrament of the Eucharist unworthily, then we are

not only bringing condemnation on ourselves but also on others in the

community, for we are inhibiting the grace of God to flow to others.

This is why St. Paul writes to

the Corinthians, “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ? Shall

I therefore take the members of Christ and make them members of a prostitute?

Never! Do you not know that he who joins himself to a prostitute becomes one

body with her?” (1 Corinthians 6:15-16). In a similar way, because we are all

members of Christ’s Body, we cannot “prostitute” ourselves by joining ourselves

to lives of sin, still thinking that we can be “one flesh” with Christ in

receiving the Eucharist.

Lest we believe that Ratzinger

wants us to focus entirely on the community of the Church, we should remember

that he ultimately sees the Eucharist as the celebration of the Church. The

focus is primarily on Christ, which is why there are certain, necessary

elements that are foundational for the Christian community, which we have

carefully noted. For some concluding thoughts, let us look to this quotation

from his work Called to Communion:

Understanding the Church Today (Ignatius Press, 1996), which, although

lengthy, will summarize well what we have discussed:

Communion means that

the seemingly uncrossable frontier of my “I” is left wide open and can be so

because Jesus has first allowed himself to be opened completely, has taken us

all into himself and has put himself totally into our hands. Hence, Communion

means the fusion of existences; just as in the taking of nourishment the body

assimilates foreign matter to itself, and is thereby enabled to live, in the

same way my “I” is “assimilated” to that of Jesus, it is made similar to him in

an exchange that increasingly breaks through the lines of division. This same

event takes place in the case of all who communicate; they are all assimilated

to this “bread” and thus are made one among themselves—one body (p. 37).

Participating in the Eucharist,

therefore, is meant to be a sacrifice of ourselves. Not only are we assimilated

into Christ’s Body, but we also become one body with those who participate in

that Eucharist, for we are all oriented toward the one goal of union with

Christ. The Eucharist is not a celebration of ourselves or an individualistic

invitation to salvation—rather, the Eucharist is how we become one flesh with

Christ and with the community, for it is an anticipation of how we shall be one

in Heaven, even as Christ and his Father are one (see John 17:21; 22; 24; 26).

Ultimately, because of the communio of

the Church, we cannot allow those publically living in sin, especially those

who are divorced and remarried, to receive Communion.

It is not so much about

separating individuals from the Church as it is upholding the true nature of

the Church, which is about communion with God and the faithful. Those who are

not properly disposed to receive Christ will only do harm to the Body because

the sacraments are not and cannot become individual means of salvation. If we

allow the divorced and remarried to receive Communion on a whim without

properly remedying their situation, we change the very nature of the Eucharist,

and in so doing, the very nature of the Church.

Therefore, as we struggle with

these questions in the Church—questions that were, in all actuality, settled long

by the unchanging doctrine of the Church—it is a reminder to us of the true nature

of the Church and a reminder to discern our own disposition to enter into the

communion of the Body of Christ.