Roberto de Mattei

Corrispondenza Romana

December 19, 2018

In December 1918, Europe celebrated the first

Christmas of peace after four years of non-stop bloodshed. The world that was

born, however, was no longer that of yesterday.

On November 3rd, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire

had signed the armistice of Villa Giusti with the Allied Armed Forces in Padua.

On November 7th, the German

Chancellor received an ultimatum from the German Socialists, who imposed the

abdication of Kaiser William II for Friday November 8th. The Grand Duke of Baden, notified the Sovereign,

who was at his General Quarters in Spa, that he could no longer rely on the

army and that a civil war was looming. Right up until the morning of November 8th,

the Sovereign manifested his intention of reestablishing order and taming the

Revolution at the head of his troops. But during the night between the 8th

and 9th everything collapsed. The Emperor’s military and civil

advisors, gathered together in Spa, insisted that the Kaiser abdicate and leave

for Holland. On November 9th he announced his abdication as Emperor of

Germany, not as King of Prussia, and entrusted the Command of the Army to Field

Marshal von Hindenburg, appointing him to negotiate the armistice. That same day the Emperor left Germany, never

to return.

On November 8th the direction of the Austrian

Social Democratic Party publically delivered a statement for a “German-Austria,

Democratic, Socialist Republic” At

midnight, the Emperor Charles I convoked to his study in the Schönbrunn

Palace, his closest advisors, Count Hunyadi and

Baron Werkmann and declared calmly: “Even

Austria is

about to collapse, influenced by the German revolution. They will proclaim the Republic

and there will no longer be anyone to defend the Monarchy…. I don’t want to abdicate and I don’t want to

flee the country…”

Some frenzied moments followed, in which

everyone in the Emperor’s entourage came up with different proposals and

suggestions to cope with the dramatic situation. Admiral Miklós Horthy, who had arrived from the Adriatic to

discuss the consignment of the fleet to the Croatians, stood to attention in

front of the Sovereign and with his right hand outstretched, he vowed, even if nobody

had asked him: “I will not rest until I restore your Majesty to the throne of

Vienna and Budapest.” Three years later,

it would be precisely General Horthy, Regent to the Kingdom of Hungary, that

would take up arms against his Sovereign in the periphery of Budapest and even have him arrested and deported, in order to maintain power in Hungary.

At 11 o’clock, the morning of November 11th,

the Prime Minister Heinrich Lammasch and the Interior Minister, Edmund von

Gayer, showed up at Schönbrunn, bringing

with them the abdication text for Charles, agreed upon by the politicians of both

the old and new regimes. The document had been approved by the Cardinal of

Vienna, Prince-Archbishop Friedrich Gustav Piffl, who, exactly a

week before, on November 4th, had celebrated Charles’ Saint’s day,

with a solemn Mass in St Stephen’s Cathedral. It was one of his priests, Ignaz

Seipel, who found the formula of compromise for the Sovereign to renounce the

throne, without pronouncing the word “abdication”. If the Emperor had not signed it, said Gayer

to the Sovereign: “this very afternoon we will see the masses of workers in

front of the Schönbrunn….and

then the few who refuse to abandon Your Majesty will lose their lives in the

attempt to resist and along with them, Your Majesty and your august family will

also be killed”.

The ministers demanded that the signing be done

immediately, without allowing any time for reflection. The Emperor hesitated.

He was a man of great nobility and character, but did not have the energy of

his wife Zita, who, at that moment, was the only one to protest with all her might,

addressing Charles with these words: “A sovereign can never abdicate, he can be

deposed and his sovereign rights can be declared lost. But - abdicate…..never, never and again never! I’d

prefer to die here right next to you. As Otto would still be here and even if

they should kill us all there would still be other Hapsburgs!”

At midday on November 11th 1919, the Sovereign

signed the act of renunciation of power, in which he had acknowledged

beforehand “the decision that German-Austria will be taking for its future

constitutional form”. In the afternoon, the Emperor and his family, after

praying in the Royal Chapel, said goodbye to the last dignitaries and headed

for the motorcars which would take them to their Hunting Palace in Eckartsau.

“Along the archways – recalls Zita – lined up in a double-row were our cadets

from the Military Academy, adolescents between 16 and 17 years old, misty-eyed,

but upright, attentive and devoted to the Emperor to the very last, worthy of

the motto they had received in the past from Maria Teresa, Allzeit Getreu

(Forever Faithful).”

On November 12th in Vienna,

the Republic was officially proclaimed. The day before, in a railway-carriage,

in the woods near Compiègne, the armistice between the German Empire and the

Allied Forces was signed. This act marked the military end of the First World

War.

On December 4th 1918, the ship, George

Washington, set out from the port of New York, for France, carrying aboard

President Woodrow Wilson and the American Delegation for the Peace Conference.

Wilson, violating international law, had personally intervened on the provisory

Socialist governments of Austria and

Germany, to enforce institutional change.

On December 14th the American President met the French Prime

Minister Georges Clemenceau in Paris. The two politicians were the main

architects of Europe’s “republicanization”, which followed the First World War.

In the victory, Clemenceau, a Jacobin mystic, saw the fulfillment of the ideals

of the French Revolution.

Wilson wanted to transform the globe

into a confederation of republics, rigorously alike, based on the United States

of America. The principal obstacle that had to be knocked down was Austria-Hungary,

the last reflex of medieval Christianitas.

Charles Seymour, one of the American negotiators of the Treaty of Versailles,

recalls: “The Peace Conference finds its place in the position as the authentic

liquidator of the Hapsburg State. (…) By virtue of the principle of self-

determination of the peoples, it was up to the Danube nations to determine their

fate by themselves.”

The Peace Conference opened in Paris

on January 18th 1919. In those very days, the terrible epidemic of Spanish ‘flu

reached its peak. In Italy it would

cause 600,000 deaths, the same number of victims in three years of war. Also

two of the three visionaries of Fatima, Jacinta and Francesco, contracted the

illness in December 1918. Francesco died on April 4th 1919. Jacinta

was taken to hospital in Lisbon where she died on February 20th

1920.

On December 22nd Pope Benedict XV,

manifested his hope for “the deliberations, which will soon be taken by the Areopagus

of peace, that the sighs of all hearts are now yearning for.” L’Ilustrazione

Italiana wrote on December 22nd 1918, that 1919, “will be the

year of the transfiguration of the world”. The illusions of the “roaring

twenties”, were quickly swept away by a new hurricane of war, which had its

premise right in the Peace Treaties concluded in Paris between 1919 and 1920.

The century that followed is considered the most terrible in the history of the

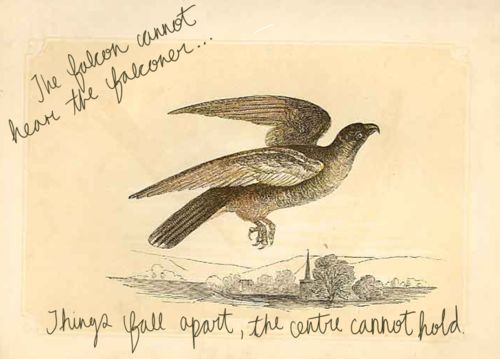

West. The verses by William B. Yeats may

be applied to it: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. Mere anarchy is

loosed upon the world.” The Holy Roman Empire was officially dissolved by

Napoleon in 1806, but Austria-Hungary continued to carry out its mission until

1918, forming the heart of Europe’s equilibrium and stability. After that, the

vortex of instability opened, which today has passed from the

political sphere to the religious one, causing the disorientation of millions

of souls.

Notwithstanding,

the Church survives the tempests that engulf Empires and each Christmas, the

Infant Jesus, invites us to abandon ourselves with immense trust to Him, like sleeping

children in their mother’s arms.

Translation: Contributor

Francesca Romana