The Catholic community in Mongolia is minuscule, numbering 1,500 faithful, which suggests that the country has not really been deeply evangelized. The presence there of the Successor of Peter presented an excellent opportunity: was it not possible, perhaps, to announce the name of Jesus Christ, with respect and cordiality towards the Buddhist listeners, and to present himself not as the bearer of a humanistic message but as what he is, the Vicar of Christ? Unfortunately, the Pope's trips are not evangelizing gestures but vaguely religious ones; the proclamation of the kerygma, as befits the apostolic office, is not primarily to be found in them. This time it was a sermon against fundamentalism: "Close-mindedness, unilateral imposition, fundamentalism and ideological coercion ruin fraternity, feed tensions and endanger peace."

St. Paul's discourse in the Areopagus of Athens (Acts 17:22-31) is a model that can be analogically applied today to the relationship of Catholic Truth with the religiosity of "the nations". The Apostle did not prepare an inter-religious salad, like the one served in Mongolia. Incidentally, we can ask ourselves what a pastoral attitude consists of, in a Christian sense.

"Fundamentalism endangers peace," headlines the Buenos Aires newspaper "La Prensa" on the Pope's warning. It is true: the progressive fundamentalism installed in Rome disturbs the peace of the Church, in which disharmony spoils its beauty. At the meeting held at the Hun Theater in the capital Ulaanbaatar, where local shamans, Buddhist monks, and an Orthodox priest were gathered, the Pontiff indiscriminately praised "religious traditions, in their originality and diversity (which) have a formidable potential for good, at the service of society". The Holy Father listened attentively as other religious, including Jews, Muslims, Baha'is, Hindus, Shintoists, Adventists, and Evangelicals, described their beliefs, and their relationship with the afterlife. Many noted that "the Mongolian yurt is a powerful symbol of harmony with the divine, a warm place of family togetherness, open to Heaven, and where all, even strangers, are welcome." On the international level, the Pope pointed out that if those who govern nations "would choose the path of dialogue with others, they would contribute in a decisive way to putting an end to the conflicts that continue to cause suffering to so many peoples."

With Buddhists seated in the front row, he recalled the persecutions of which they were victims at the hands of the region's Communist dictatorships: "May the memory of those sufferings give us the strength to transform the dark wounds into sources of light, the ignorance of violence into wisdom of life, the evil that ruins the good that builds."

"The fact of being together in the same place is already a message," affirmed the Vicar of Christ. What would Soeren Kierkegaard have thought of that message - especially of the speeches? Surely that it meant the abolition of Christianity. The Kierkegaardian salt, having lost its flavor, entered into the composition of the salad together with Buddhist writings, Gandhi, and St. Francis of Assisi, all quoted in the mass. The Mass, celebrated in a sports stadium, was attended by many Chinese pilgrims, defying the prohibitions of the Beijing regime, which did not allow the bishops to leave the country. They traveled in trains for more than twenty hours to see the Pope; they prudently avoided talking to the press, being filmed or photographed. The liturgical celebration was attended by about two thousand faithful, among them pilgrims from the neighboring Asian colossus. During the Mass, the Pontiff spoke again to China; he asked Catholics "to be good Christians and good citizens." Words measured carefully.

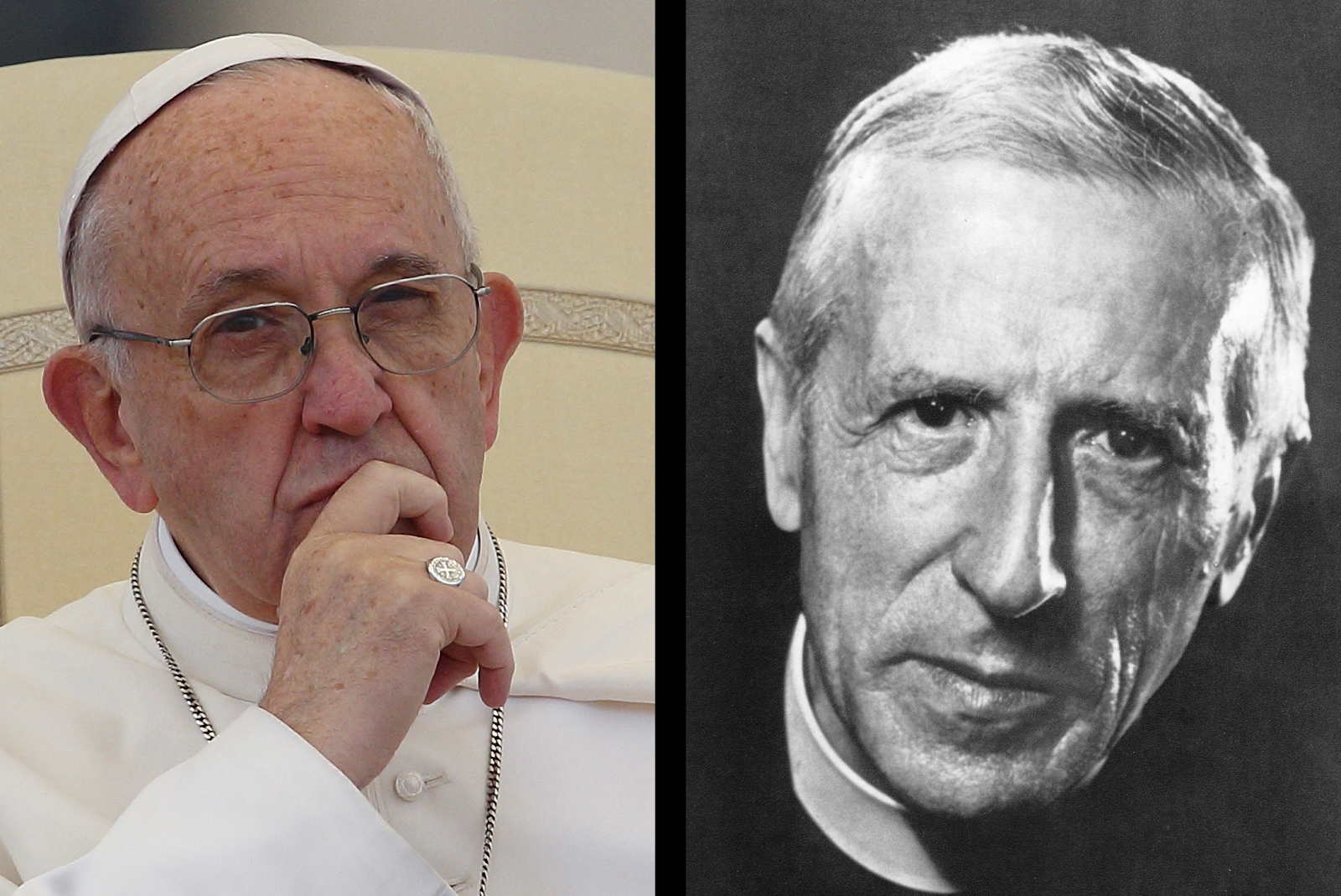

The orientation of the Pontificate was clearly shown during the trip to Mongolia. It occurs to me to relate it to a recent expression of Pope Bergoglio, who envisioned his successor as John XXIV. In my article "The New Pope", I sketched what seems to me desirable for the next pontifical turn. Why couldn't the successor be Pius XIII, or Urban IX? The eighth in the series reigned between 1623, and 1644. It would be a tribute to the Urbs, the eternal Rome, which occupies a privileged place in the heart of all Catholics.

The designs of God's Providence are inscrutable.