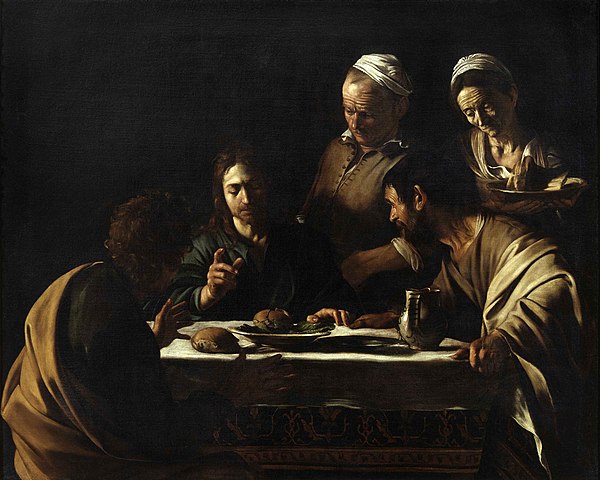

Our Gospels tell us very little of the post-Passion appearances of Jesus. In compensation for the dearth of anecdote, artists have seized that encounter on the road to Emmaus. A popular motif for centuries, it challenges artists to picture a revelation at once quotidian and sublime. Few have met that challenge with the power and subtlety of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Christians profess faith in Jesus as True God and True Man, his humanity and divinity indivisible. That faithful unity loses something of its purity in the effort of depiction. It is no easy thing for Western verisimilitude to suggest “the radiance of the glory of God,” as Paul states in Hebrews 1:3, without tilting the Incarnate Word into something dewy and ethereal, making human flesh a costume rather than—Paul again—“the exact imprint of his nature.” Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus reminds us that the resurrected Christ and the Galilean man are one.

Caravaggio. Supper at Emmaus (1601).

Caravaggio painted two renditions of the theme. The first (1601, above) hangs in the National Gallery, London. The second, painted five years later, is in the Brera, Milan. Completed while he was on the lam from Rome for having murdered a well-known pimp, the 1606 variation (below) is subdued. Gestures are restrained, color is understated, the table cleared of all but bread and wine, elements of the Eucharist. Atmosphere is darksome, the Christ figure more conventional. Its greater solemnity brings Caravaggio’s unflinching realism—not customary at the time—within the orbit of traditional patterns of depiction.

Yet it is the earlier work that conveys the drama of that instant of recognition with greater potency. And particular earthiness.

Seen through devotional eyes, the later painting is more comfortable. The facial type of the Risen One is more consistent with what we—and the 17th century audience— are accustomed to. But the shock of understanding precedes reverence. Caravaggio, a man intimate with trauma as both agent and casualty of it, summons that bombshell moment of comprehension in the dynamic gestures of the two disciples.

Caravaggio. Supper at Emmaus (1606).

Penetrated and carried away by the shattering wonder of realization, one disciple grips his chair, pushing it back and leaning forward as if to bolt from his seat. The other flings out his arms in a reflective spasm of astonishment. The innkeeper, comprehending none of it, simply looks on. His presence is inert but his shadow is not. Falling behind the Christ, it serves a double purpose: to heighten the radiance of Christ’s illuminated face; and to extinguish the expected halo.

Christ is uncharacteristically beardless in the initial version. Why? Some suggest that a clean-shaven face served purposes of disguise. Does the Gospel of Mark not say that he “appeared in a different guise” (alia effigie in the Vulgate)? But it could be more mundane than that. Working in Rome, Caravaggio was familiar with Michelangelo’s Christ in Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Painted a century earlier, that majestic Apollonian figure is without a beard. In every age, painters take what they need from each other. Moreover, Howard Hibbard, writing on Caravaggio, called attention to Early Christian images of a youthful, shaven Christ (such as one on the 4th century sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, unearthed in 1595). Caravaggio’s era was one of renewed interest in Early Christian art and ritual.

Certainly, the countenance of the painter’s 1601 Christ is more ethnic—Semitic—than Apollonian. And his disciples are hardscrabble men. Note a torn sleeve, and a workman’s vest. This is not supper for few cultivated folk as in the Vatican’s tapestry rendering of the theme. Leo X commissioned the drawings from Raphael’s studio in 1515. Some years later, Clement VII ordered it woven in Brussels. All wool, silk, and gold threads, the tapestry exchanges a display of wealth for the condition of humanity that distinguishes both of Caravaggio’s interpretations.

Supper at Emmaus. Hall of Tapestries. Vatican Museums.

PaoloVeronese takes Luke’s report on a similar excursion of flattery toward patrons. He translates the supper into a state banquet in a Venetian palace. As testament to Venice’s legendary splendor it is a marvelous painting. As a depiction of the gospel account, it is oddly comic. A pious Christ—eyes rolled heavenward, a glowing nimbus around his head—appears dislocated. In my mind’s eye, Luke gives way to Stanley Kramer, and we are in the neighborhood—forgive me—of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. The sentimentality of Christ figures is a common misstep.

Paolo Veronese. Supper at Emmaus (1560).

But let us stay with Caravaggio.

The lush still life on the table in his first version of the supper, edited out in the second, is partly a tour de force. The painter is showing off his proficiency in a subject struggling at the time to achieve independent existence. In the main, still life was not yet a self-reliant genre. It still required a pretext, commonly the attributes of saints: St. Cecilia’s viola, or St. Dorothy’s flowers and apples. A roast fowl on a platter and a basket of over-ripe fruit within a sacred scene could easily have struck patrons as unedifying.

A shame if it did. The normalcy of the table setting lends vitality to the gospel telling, compressed by Luke to the miraculous. Caravaggio’s homely ensemble roots miracle where it abides—in the nobility, no less than the misery, of ordinary life. It sets before weary, anxious men a summons to refreshment and nourishment that succeeds as both anecdote and symbol. The transcendent bursts into the prosaic in the blessing of a meal. Life crucified passes to life arisen in the breaking of bread.

In Luke’s recounting, the Risen Lord has sat down with the disciples at their request: “Stay with us, for it is nearly evening, the day is almost done.” That ancient invitation serves us now as prayer. Our day, too, is almost done.

.jpg/1600px-Supper_at_Emmaus-Caravaggio_(1601).jpg)