Rorate readers will be aware of the groundbreaking interview Kevin J.

Symonds conducted with Fr. Murr for the October 2020 issue of Inside the Vatican, which was also

published at Rorate

on October 10. Interested readers may want to read that interview first in

order to gain more understanding of context for the present one, which was done once again for Inside the Vatican.

In the previous interview, Fr. Murr told us about his friendship with

Mother Pascalina Lehnert, the “right hand” of Pope Pius XII for several

decades. In addition to this discussion, Fr. Murr made some notable

revelations about what was going on at the Vatican in the 1960s, and 1970s.

The interview below follows up on these revelations with the theme of “where

do we go from here?”

|

|

Cardinal Baggi (L) and Cardinal Benelli (R)

|

“BY THEIR FRUITS YOU SHALL KNOW THEM”:

KEVIN SYMONDS’ SECOND INTERVIEW WITH FR. CHARLES MURR

ITV: Thank you, Fr. Murr, for sitting down again with Inside the Vatican. In our previous interview, you spoke of your association with Cardinal

Edouard Gagnon and Msgr. Mario Marini. These two men worked closely with the Sostituto

of the Secretariat of State, Cardinal Benelli. You yourself, however, did

not enjoy the same association with Cardinal Benelli...

I was twenty-four years-old when I met and became friends with the newly

appointed minutante in the Vatican Secretariat of State, Monsignor

Mario Marini. Soon after, Marini introduced me to another extraordinary man

who would play a major role in my life, his good friend, Archbishop Edouard

Gagnon (1918–2007). Gagnon and Marini were respected friends and confidants of

Archbishop Giovanni Benelli (Sostituto of the Secretary of State); I

was not part of that inner circle. I knew Benelli, of course, and spoke with

him many times, but I knew my place. Once, on Lago di Bracciano I was at table

with him and Monsignors [Guillermo] Zanoni and Marini. I remember talking as

little as possible. With Benelli, I knew my place and kept it.

Why did you think of your relationship with Benelli in this way?

To begin with, Giovanni Benelli was Giovanni Benelli! He was one of the most

powerful men on earth; brilliant, a strategizer and deal-maker

par excellence, the #1 Vatican diplomat, a man on familiar terms with

popes and princes, patriarchs and presidents, world leaders of all sorts. I,

on the other hand, was a greenhorn American student of philosophy; absolutely

no one of consequence. Those special times that I was privileged to be in

Benelli’s company were times I knew I was in the presence of greatness.

How did then Archbishop Gagnon become appointed by Pope Paul VI to be the

Apostolic Visitator to the Roman Curia?

This was Archbishop Benelli’s call. Paul VI was convinced that “the smoke of

Satan” had entered the Church (as he said publicly in June of 1972). In 1975,

he called for an investigation of the entire Roman Curia. Benelli assured the

pope that he had just the man for the job: Edouard Gagnon. And as soon as

Gagnon accepted the awesome responsibility, he “hit the ground running,” as

the expression goes. At the pope’s insistence, the in-depth investigation of

the Roman Curia—no small assignment, let me assure you—was to be Gagnon’s

full-time job, start to finish.

Other people helped Gagnon with the visitation, yourself included. Could

you name a few of these people and how they were involved?

Gagnon was assisted by several people during the three-year investigation.

Most important among them was his trusted friend and compatriot, Msgr. Robert

Tremblay (I believe the good man has already gone to God). When Gagnon needed

a second opinion on this or that legal matter, he called upon Msgr. Giuseppi

Lobina, Professor of Law at the Lateran University. The archbishop was also

assisted by a very competent and dedicated Italian secretary, a laywoman,

whose name I simply cannot recall. I am ashamed for not remembering it; I knew

her and her husband in Rome and she visited me in New York. She typed up every

word of Gagnon’s investigation and prepared it for the pope to read.

Of all these people, are you the last living member of this association?

To the best of my knowledge, yes.

Could you tell us a little more about your personal association with

Gagnon?

Following my ordination to priesthood [1977]—I was ordained by Cardinal

Pericle Felici and Archbishop Gagnon—Marini and I moved into the Lebanese

Residence for Priests on Monteverde Vecchio, just off the Janiculum Hill.

Archbishop Gagnon soon joined us, mainly for security reasons. Because of his

investigation, threats had been made on his life and his quarters at the

Pontifical Canadian College had been broken into and ransacked more than once.

|

| Cardinal Gagnon; Alice von Hildebrand |

That last fact is particularly interesting. In 2001, the renowned

philosopher Dr. Alice von Hildebrand spoke

about Gagnon’s visitation of the Roman Curia. She revealed that the

dossier that he submitted to the Holy Father had been stolen out of a safe

in a Vatican office. What do you know about this story and can you say

anything about it?

Dr. von Hildebrand could not be more correct. The dossier was stolen from a

safe that was broken into at the Congregation for the Clergy. That was not the

first or last time someone attempted to steal the explosive package of

information. As I mentioned earlier, Gagnon’s private rooms at the Pontifical

Canadian College were broken into and so was his office at San Calixto [in

Trastevere]. This was why he moved into the Lebanese Residence on Monte Verde

Vecchio with Mario Marini and me. After Archbishop Hilarion Capucci arrived

and took the suite right down the hall from us, we three—Gagnon, Marini and

myself—found ourselves in the most secure spot in all of Rome. No one could

get close to Gagnon or his private documents there. No one.

What made this the “most secure spot in all of Rome?”

Archbishop Hilarion Capucci’s presence in our residence made it one of the

most secure places—not only in Rome, but I dare say, in the entire world.

Capucci was a very high profile Syrian prelate; the Melkite Archbishop of

Jerusalem. He had been imprisoned in the mid-70s by the Israelis, charged with

smuggling arms to the Palestinians. The Israelis released him to the Vatican

on one condition: that he never again return to the Middle East. From the day

he arrived at our residence, the day of his release, there were two

surveillance vans parked outside the front gates of our house, 24/7; one with

armed Israeli agents; the other with armed Syrian agents. No one, but no one,

came within a hundred meters of the Lebanese Residence undetected. Often

enough, visitors to the house were stopped, questioned, had to show

identification, and were frisked for weapons.

No doubt about it: Archbishop Gagnon lived in the safest, most secure place in

all of Rome! He continued his work freely, knowing that the possibility of

being murdered or robbed, or both, were now, thanks to our dear friend

Archbishop Capucci, non-existent. I

wrote

a book based on one of my more extraordinary experiences with His Excellency.

The last time I visited Archbishop Capucci was in 2014, at Santa Marta, in the

Vatican. He was a man I came to respect greatly.

|

|

Cardinal Benelli; Archbishop Hilarion Capucci

|

Why do you think the dossier had been stolen in the first place?

That’s simple. The results of Gagnon’s three-year investigation contained

damning evidence against several major figures in the Roman Curia; Cardinal

Sebastiano Baggio of the Sacred Congregation for Bishops and Bishop Paul

Marcinkus, President of the (so-called) Vatican Bank, to name but two of the

more infamous. There were any number of people who wanted to see if the

dossier contained information detrimental to their persons and/or their

“all-important” careers.

Was the dossier preserved or does its theft mean that it was permanently

lost?

Archbishop Gagnon knew to make a duplicate copy for himself. He was of the

opinion that those who attempted to steal the dossier wanted to know its

contents and so empower themselves with information they could use to

blackmail political enemies and further their own pathetic careers—not

necessarily to destroy it.

Would you say then that people feared Gagnon?

In Rome, in those times, whenever Edouard Gagnon’s name was mentioned (where

two or more were gathered), invariably someone would add: “The two who know

all: the Holy Ghost and Edouard Gagnon!” In answer to your question, yes,

Cardinal Gagnon was feared—by those who had reason to fear him, those guilty

of grave misconduct. He was respected and admired by those who had no reason

to fear him.

You have spoken highly of Msgr. Mario Marini. Very little, however,

is known about him in the public forum. He appears to have worked

at the Secretariat of State as well as the Pontifical Commission

Ecclesia Dei. Some Vatican documents bear

his name as Undersecretary. The Archbishop of Seattle, Paul D. Etienne,

was friends

with

him. He also wrote

a book with meditations about Jesus with a forward by Cardinal Marc

Ouellet. Could you tell us more about Msgr. Marini?

To call Mario Marini “extraordinary” would be a tremendous understatement.

Personally speaking, Mario was the man who had the greatest impact on my life.

Fourteen years my senior, he was strong-willed but patient, knowledgeable on

almost any subject, and good-humored. He was a man’s man; toughened by what

life threw his way. His mother and father, and even his grandparents, were

committed Marxists and, as such, extremely anticlerical. The day he completed

his doctorate in civil engineering, he informed his parents that the following

morning he would be leaving for the seminary in Milan. His mother slapped him

hard across the face and shouted at him: “Better a whore for a daughter than a

priest for a son!” When he was ordained and offered his first Mass in Ravenna,

the church was only a stone’s throw from the Marini family home but his

parents did not attend. Mario Marini knew the cost of loving Christ and His

Church.

Once inside the Vatican, Mario never looked for personal fame. I cannot

emphasize enough how different this made him from the majority of those who

make up the Roman Curia. He remained faithful to God, to his calling, to the

Church, and to the pope, and was happy in his role as one of the powers behind

the throne. You never found him at a papal ceremony, at any public affairs of

State or Church, or in any too public place. He worked tirelessly and very

quietly for the good of the Church. He was a great friend and confidant of

many cardinals, but Giovanni Cardinal Benelli was the man he most admired.

Benelli was my mentor’s mentor.

Can you tell us how Msgr. Mario Marini came to work for the Holy See?

While Cardinal Montini was Archbishop of Milan he paid for Mario’s seminary

training, given the Marini Family’s blatant anticlericalism. Later, in 1963,

when Montini became pope [Paul VI], he invited Marini to work for him in the

Secretariat of State. John Paul II admired him and sought his opinion on many

important matters. Benedict XVI counted on him for counsel and support.

In fact, since many who read this interview probably share your interest in

matters liturgical, let me share a story that Marini shared with me shortly

before his death. He had just been named Secretary for the Congregation for

Divine Worship and the Sacraments when Pope Benedict congratulated him

personally and told the man who held a doctorate in civil engineering before

entering the Milan seminary and who later took a second doctorate in Sacred

Theology, that it was refreshing to know that no professional liturgists were

among the Divine Worship department heads. The pontiff felt greatly relieved

that he could now speak and deal rationally with all involved. I am reminded

of the old joke about the difference between a liturgist and a terrorist: you

can negotiate with a terrorist! Evidently, Pope Benedict felt the same way.

What became of your friendship with Msgr. Marini?

In 1985, Mario and I had a falling out and didn’t really communicate for

years. I detailed the story of what happened between us in my book,

The Society of Judas. Though Mario and I reconciled when I suffered a heart attack in Rome

(2005)

[i]—imagine, from a hospital bed in the Clinica Gemelli, opening your eyes to

see the man who called you to priesthood standing at your side, administering

the last rites!—I was shocked when, in March of 2009, I received a sort of

“out-of-the-blue” phone call from him and listened to his apology. He asked me

to come to Rome so that we could speak in person and really renew our

friendship. I readily agreed, of course... I had no idea that would be the

last time we would speak on this side of the divide.

There are Internet reports of Msgr. Marini’s death a couple of months

later. In its obituary, the blog Rorate Caeli referred

to Marini as a “true friend of Tradition.” Can you tell us anything about

his death?

As soon as I learned of Mario’s death, I contacted a mutual friend of ours at

the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith [CDF]. He confirmed the news

and explained that the cause of death was cancer of the liver. It seems Mario

told no one just how serious his condition was.

|

|

Fr. Murr with Mother Pascalina

|

Your book The Godmother

talks about how the book’s real power is in the story of true Christian

friendship. This theme shines through very clearly with respect to your

relationship with Mother Pascalina. What would you say of its application

to your relationship between Gagnon and Marini?

Well, almost immediately, Marini, Gagnon, and I became friends. The mutual

spark of “simpatico” was there; each of us loved Christ Jesus, possessed an

integral and orthodox Catholic faith, and had a special love for Christ’s

Bride and our mother, the Church. We were also keenly aware that the present

state of that Church was somewhere between lamentable and alarming. All of

this united us strongly.

The Godmother also references how some people would be more attracted to the more

“sensational” elements contained within the book. What would you say to

those people who are interested only in the “sensational” aspects of your

book?

While the “sensational” can certainly grab and hold your attention, it has no

real substantial saving graces. Amicitia [friendship] is the saving

grace. It is precisely what God calls us to when He tells us through His Son:

Vos autem dixi amicos [I have called you friends].

For the sake of clarity, I would like to turn to some of those more

sensational revelations. As the likely last-living member of Gagnon’s

associates during his visitation, your testimony about Archbishop Annibale

Bugnini being a Freemason is as provocative as it is authoritative. Were you

aware of the gravity or impact that your testimony might have upon the

larger Catholic world, especially to liturgical scholars?

Well, yes and no. At the risk of sounding cynical, I don’t expect to change

the mind of anyone who finds it too conspiratorial to consider that the likes

of Archbishop Bugnini (who, among other misdeeds, redesigned the Catholic

Mass) and Cardinal Baggio (who, among his other misdeeds, reconstructed, or

should I say “deconstructed,” nearly the entire Catholic episcopacy) could be

Freemasons. Nor do I expect the average man to believe that

Propaganda Due, the organization that set out to destroy the

Vatican’s financial base and bring Catholicism’s central government to her

knees, was a lodge of Italian Freemasons. Nonetheless, I do find it rather

compelling that each Freemason involved in this dastardly plot was found

guilty by the Italian Courts and ended up murdered, committed suicide, or died

in prison. To a great degree, I sympathize with those who don’t, who

can’t, believe such things. For twenty-seven years, I numbered among

them.

Furthermore, given the modernist chaos presently rampant within the Roman

Catholic Church, even if the majority of liturgical scholars, theologians,

philosophers and, as you say, “the larger Catholic world” would come to see,

beyond the shadow of a doubt, that men like Bugnini and Baggio were

high-ranking Freemasons, I doubt it would bother them in the least.

Why do you believe that the majority would not be bothered by this

fact?

Because from 1965 to the present, the majority of Catholics—and by “majority,”

I mean the majority of the minority who haven’t already left the

Church—faithfully followed their priests and bishops who, themselves, happily

followed—some of them even surpassed—Archbishop Bugnini. The result is that

the “majority of that Catholic minority” are, for all intents and purposes,

the third Protestantized generation of Catholics. One wonders the degree of

delight it would have given Bugnini to see the practical results of his new

Mass.

Besides, I just learned—and this is public knowledge—that Papa Bergoglio has

appointed a priest and a Freemason to a Vatican position. Monsignor Michael

Heinrich Weninger, chaplain to three Masonic Lodges in Austria, is a

member

of the Pontifical Commission for Interreligious Dialogue. Monsignor Weninger

is also the

author of Lodge and Altar: On The Reconciliation of the Catholic Church and Regular

Freemasonry. Therefore, why would it be hard to believe that the likes of Bugnini and

Baggio helped pave the way for him and others so free-thinkingly inclined? God

help us!

Indeed, one has to wonder how it is that Weninger could believe

himself safe to declare openly his membership within Freemasonry. What,

though, do you believe are the “practical results” of Bugnini’s work?

Sadly, I refer to the “Mass as sacrifice” being replaced by the “Mass as

get-together;” the vertical bar replaced with the horizontal. This, of course

and tragically, results in the appalling lack of belief in the True Presence

of Jesus Christ, Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity, and the lack of reverence for

the Mass and Blessed Sacrament, and the watered-down importance of the seven

Sacraments in general. While many may not be able to accept Bugnini’s Masonic

kinship, how can anyone not accept the Masonic results of his labors?

Igitur ex fructibus eorum cognoscetis eos [By their fruits you shall

know them], the Lord reminds us. If Bugnini’s liturgical reformation—in

particular, that most sacred mystery of our Catholic Faith, the Holy Sacrifice

of the Mass—does not loudly and clearly cry out: “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” then what does it cry out?!

In The Godmother, you make reference in chapter 19 that the idea of “promoting”

Archbishop Annibale Bugnini to Pro-Nuncio to Iran was Msgr. Marini’s idea.

Is this accurate, and, if so, could you elaborate?

Perhaps it would be better to say that Marini made a major contribution to the

planning and execution of the idea. Mario understood better than most the

age-old “promoveatur et amoveatur” [promote someone to get rid of

him] concept. The Vatican actually raised this adage to an art form. In fact,

Marini himself never accepted the promotion to bishop—which had been offered

to him, twice and personally, by his mortal enemy Sebastiano Cardinal Baggio

in the frantic hope of getting rid of him for good! At any rate,

Mario, Giovanni Benelli’s right-hand man in such things, had to wait not only

for the correct opening for Bugnini to fill (i.e., to be exiled to), but also

to make sure the one or two Bugnini supporters on the planning commission

would be absent from the meeting that decided Bugnini’s fate.

I’m not sure whether it was the [1976] Annibale Bugnini “promotion” to Nuncio

to Iran or the [1977] Mario Pio Gaspari “promotion” from Apostolic Delegate to

Mexico to Nuncio to Japan—perhaps it was in both cases, since both men were

Cardinal Baggio protégés—but for the planned promotion to succeed,

Cardinal Baggio had to be absent from the committee meeting in the secretariat

or he would have blocked the promotion(s). In one of the cases, I remember

that Baggio had to be sent (by order of the Secretariat of State) to represent

the Holy See at some historical commemoration event in Northern Italy, so that

he would be absent from the afternoon secretariat meeting and the

“promotional” vote would be successful. This and other such tactics were how

Marini (and the Benelli Boys) got around Freemasonic attempts at blocking

progress. “Fight fire with fire,” Mario liked to say.

The revelation about Bugnini being involved with the Freemasons casts a

non-negligible shadow upon the liturgical reforms, as we talked about in our

previous interview. The obvious question arises: “Where do we go from

here?”

There are differing ways to look at this question. Some people have proposed a

quick and simple solution: Bugnini’s membership in Freemasonry means we should

hit the reset button on everything that happened from the publication of

Sacrosanctum Concilium to the present. True, as a Freemason, Bugnini

would be

persona non grata to many people, dare I say a reprobate and

a prime candidate to be

excommunicado, and there is reason to

question his authority. The problem here is that Paul VI lent

his authority to the changes—a fact that Bugnini was rather keen to

emphasize in his book

The Reform of the Liturgy (1948–1975). Thus, papal authority is bound up with this question and we have to be

mindful of the fact.

Another idea presently circulating is that Bugnini’s “reforms” extend back to

the Pian Holy Week reforms of the mid-50s. Therefore, those reforms are

similarly under scrutiny. This belief is mistaken. Mother Pascalina herself

refuted the idea that it was Bugnini who “masterminded” those particular

reforms. I spoke about this in chapters 15 and 21 of The Godmother.

In short, her answer was that those reforms were all the Holy Father’s [Pius

XII] doing. She emphatically denounced Bugnini taking credit for them.

What, then, do you believe should happen with the Latin liturgy?

In its present, rather lamentable state, the Latin liturgy cries out to be

made whole. I am no great authority on matters liturgical. However, since you

ask my opinion, let me repeat what Sister Pascalina Lehnert told me in 1975.

While Pope Pius XII was working on his plans for a Second Vatican

Council—studies, investigations, and schemas that, ultimately, he abandoned,

as he came to see that the world’s bishops “lacked the maturity to bring it

[the Council] to fruition”—the Holy Father actually considered allowing

certain parts of the Mass in the vernacular. As I understood it, Pope Pius

gave serious thought to allowing the Scripture readings and the Mass

Propers—in other words, the “variable” parts of the Mass—to be proclaimed and

prayed in the vernacular. The Ordinary of the Mass—that is, the unchangeable

parts (i.e., the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar, the Offertory, and above

all else, the Roman Canon, etc.)—would remain untouched and in the official

language of the Western Church: Latin. From the moment Mother Pascalina shared

this, it seemed obvious to me that these were all the “allowances” that might

have helped make the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass better understood and

appreciated by modernity. She also told me that turning the priest away from

God and toward the congregants was so absurd a concept as never to have been

considered by His Holiness.

What would you say is the one liturgical innovation that concerns you

most?

It is the blatant disrespect for the Holy Eucharist, specifically in the

reception of “Communion in the hand” while standing in line as at a fast-food

stand in a mall. The proper way to receive this august gift of God is on the

tongue while kneeling.

Why are you so opposed to Communion in the hand?

Because of how tremendously effective it was for all the Protestant

“Reformers” (Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, et al.), who used it to destroy “that

Catholic superstition” of Transubstantiation. If communion in the hand helped

them to destroy belief in the Real Presence, then it stands to reason that to

restore reception of the Holy Eucharist on the tongue while kneeling will

foster the august Catholic belief in transubstantiation and dispel any

Protestant heresies concerning the Eucharist today. The tried and true path

must be retaken to underscore the Eucharist’s sublime sacred reality. Those

steps are long overdue!

The suggestions I enumerated would have required no wrecking crews smashing

our altars to smithereens, no demolition of our sanctuaries, no hauling away

of dumpsters filled with sacred reliquaries and statuary, no senseless

liturgical committees producing endless opinions on matters on which they had

no right to opine, no Eucharistic sacrileges clamoring to heaven for

vengeance, no undermining of anyone’s Catholic Faith, no blasphemies and no

heresies, formal or material. The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass would have been

preserved intact.

Simply put: what The Bugnini Brothers Demolition Company did to our Mass and

Sacraments was far more than disrespectful, disgraceful, inorganic, and

senseless; it was, in a word, anti-Catholic.

In 2005, the liturgical scholar Dom Alcuin Reid, published

a book about the organic development of the liturgy. Why is this organic

nature of the liturgy an important consideration?

Because that is how, from their very liturgical beginnings and through two

thousand years of development, we came to receive our Mass and our Sacraments.

Pope Benedict XVI, then Cardinal Ratzinger, began explaining and developing

this in his book TheSpirit of the Liturgy and later, step by

little step, throughout his pontificate.

Others have posited that we ought to look at what the Council Fathers

actually intended to do with the reforms as stated in Sacrosanctum Concilium. What would you say to this idea?

Well, since most of the Council Fathers are no longer with us, to look at what

they “actually intended” to do with the reforms (as stated in

Sacrosanctum Concilium) would be to risk more misinterpretations,

would it not?

That is a possibility, yes, but there is something to be said for taking Sacrosanctum Concilium

on its own terms and having the right people in place who have the attitude

of “sentire cum ecclesia” (to think with the Church) to implement proper

reform. That matter aside, what would you propose people do to gain some

insight?

I believe that now, with more than half a century passed since the conclusion

of the Second Vatican Council, it is time to reconsider the entire matter,

calmly, intelligently, patiently. I’m smiling—remembering Cardinal Gagnon’s

personal rebuff when, only half-jokingly, I suggested that a “Vatican III” be

convoked to figure out and deal with Vatican II! “Bah!,” the cardinal huffed,

“and give those scoundrels a second chance at destroying what they failed to

destroy the first time? God forbid! Never!”

Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò recently rendered his opinion that we should

reconsider Vatican II. What do you make of his remarks?

When I first read Archbishop Viganò’s statement that the Council, in essence,

be declared a “mis-Council,” my eyes widened in surprise—about as much as they

did when I first read Pope Benedict XVI’s claim that the (Tridentine) Latin

Mass had never been abolished or forbidden to be offered, as I distinctly

remember it being otherwise. I was very surprised by the forwardness of

Viganò’s suggestion. Many a churchman (high and low) has been thinking such

thoughts—some for more than fifty years—but no one dared speak it aloud until

Carlo Maria Viganò pronounced it recently!

So you agree with Viganò’s assessment of Vatican II?

While I certainly understand where Archbishop Vigano is coming from and

sympathize with him, I cannot completely agree with him that the Second

Vatican Council be declared illegitimate. You can not just cancel or nullify

an Ecumenical Council, convoked by a pope and (at his death) continued by

another pope, in which more than 2,500 bishops from all points of the globe

assisted. No, I believe that on those matters where the Council is dangerously

ambiguous, it must be clarified. I answer similarly to those who insist Pope

Bergoglio [Francis] clarify some of his own remarks.

You touch upon a very controversial and “touchy” subject: critiquing a

reigning Roman Pontiff. With all due respect to Pope Francis, what do you

say to those who question him?

Firstly, he has the right to face his accusers and, secondly, he has the

right, as well as the moral obligation, to answer their specific charges,

whether those charges be of formal or material heresy, or even of misspeaking.

If he has declared [something] erroneously, he must clarify his statements.

His clarifications must agree with what the Magisterium of the Church has

taught for two thousand years. As with the Second Vatican Council, the pope,

too, must be held accountable.

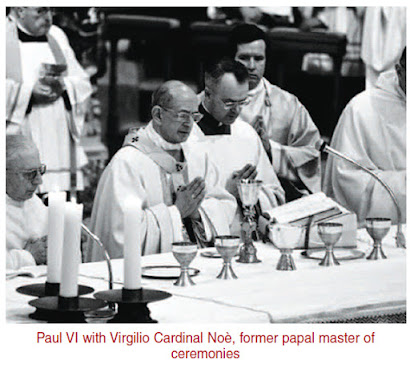

I’d like to return to the subject of liturgical matters. Virgilio

Cardinal Noè, Paul VI’s former papal master of ceremonies, once clarified

in 2008 that Pope Paul VI’s statement about the “smoke of satan” entering

the Church pertained to abuses with the liturgy. This claim indicates that

Paul VI was

concerned with liturgical abuses after the Council had ended. Why, then,

would he not have followed through with such a concern after learning

about Bugnini?

While no doubt Pope Paul’s “smoke of Satan” remark included liturgical

abuses—the Vatican was being inundated with reports of the most outlandish,

sacrilegious, and even blasphemous liturgical abuses from all around the

world—Msgr. Noè’s answer seems suspiciously self-serving.

How does it seem to be “self-serving?”

By 1972, tens of thousands of priests were “hanging up the cassock,” hundreds

of thousands of nuns had abandoned their apostolates and then their vows—by

1975 that number had grown to half a million ex-nuns—Catholic theologians and

seminary and college professors were openly critical of the Magisterium and of

the pope himself, particularly of his 1968 Encyclical,

Humanae Vitae.

In other words, the billowing over-abundance of smoke could hardly be limited

to liturgical abuses. The Church was dealing with

actual apostasy, as

defined by St. Thomas Aquinas in the

Summa Theologiae. Besides, from the time Virgilio Noè became undersecretary of the

Congregation for Divine Worship in 1975, and then, in 1982, became Secretary

of the same, liturgical abuses did not diminish; in fact, many in the Roman

Curia accused Noè himself of encouraging some of them.

Are you at liberty to mention any names of Noè’s accusers?

It was being said by quite a few men I knew in the Curia that there seemed

little (if any) difference between Noè and the “dearly departed” Bugnini. Ed

Petty (later, Msgr. Petty) and I were two of Noè’s favorite acolytes for papal

ceremonies in the mid-1970’s. In May of 1977, Noè also showed up at my

ordination—just to see who was there. I talked about this in chapter 29 of

The Godmother. Noè’s ready answer to anything he himself did not like

or want done was always the same: “Il Santo Padre non piace” [the

Holy Father doesn’t like it]. He hid behind Pope Paul VI—avoided taking

personal responsibility for his decisions. However, when Pope John Paul II

came along, and paid Noè no heed (almost pushing him out of his way on

occasion) and went to mingle with the crowds after different liturgical

events, many a priest, bishop, and cardinal nodded and smiled in agreement

with the new papal attitude toward the master of ceremonies.

Speaking of Paul VI, let us return to the topic of Archbishop Gagnon and

the Apostolic Visitation that he conducted. What happened when he presented

the dossier to the Holy Father?

When Archbishop Gagnon presented Pope Paul VI with the final report of his

three-year investigation, the pope pushed the results off to one side of his

desk and told Gagnon that he simply wasn’t up to reading it; that he would

leave it and its execution to his successor. Paul VI died some 50 days later.

Why would Paul VI treat the results in such a manner when it was he who

commissioned it in the first place?

Age. Fatigue. Weariness. Feebleness. Anxiety over the proximity of death.

Perhaps the profound disillusionment of having started a pontificate with so

much hope and ending it in such a state of despair. Of course, I’m playing the

psychologist here—only guessing at what might have motivated him… Still, I

think it’s a rather educated guess. Gagnon saw it this way, as well. Naturally

the archbishop was unhappy with the papal response—but he understood the pope,

all the same.

Paul VI died and Papa Luciani [John Paul I] was elected to succeed him. The

short-lived pontificate of John Paul I is well-known. Was Gagnon able to

present the report to the new Holy Father? If so, what can you tell us of

this event?

Within days of Luciani’s election to the See of Peter, Archbishop Gagnon was

summoned to a private audience with him. This meeting was at Cardinal

Benelli’s insistence with the new pope. John Paul I had already decided to rid

himself of Paul VI’s Secretary of State, Jean Cardinal Villot, and replace him

with Giovanni Cardinal Benelli. Most unfortunately for the new pope, his

timing was off. The correct moment to have made that major change in

government was toward the end of the Conclave that elected him; right after

receiving obeisance from each of his electors. That would have been the

perfect time for the new Pontiff to have summoned four burly Swiss Guards and

ordered them to escort the former Secretary of State back to France. However,

Pope John Paul I—a total outsider when it came to understanding and dealing

with the Roman Curia—rather than present Giovanni Cardinal Benelli as his new

Secretary of State, his “right-hand man,” actually reinstated, “for

the time being,” every member of the Roman Curia in his post! A fatal mistake.

Why was it a “fatal mistake?” What was so bad about Villot?

Throughout the 1970s, there were voices in the loggia whispering that Jean

Villot was a French Freemason. For the record, however, no such thing was ever

proven—and by “proven” I mean that, to the best of my knowledge, no concrete

evidence ever confirmed this. The whispers remain just rumors. That said, Jean

Cardinal Villot was an ally and supporter of Sebastiano Cardinal

Baggio. In the 1978 papal election, Villot lent his full support to Baggio.

Qui se ressemble s’assemble [birds of a feather flock together],

as the French say. Both Villot and Baggio were well established enemies of

Giovanni Cardinal Benelli. Thus, when the newly elected Pope John Paul I

confirmed Villot as his Secretary of State, “for the time being,” this was a

grave mistake. By way of analogy, think back to Friday, January 20, 2017. The

President of the United States has just been sworn into office. Imagine, if

you can, Donald John Trump turning to Hillary Rodham Clinton and, in front of

God and the whole world, asking her to continue on as his Secretary of

State—“for the time being.” Hard to imagine, you say? Do I hear,

“impossible”? Well, essentially, that is what Papa Luciani did upon

his election as pope!

Fair enough. How then did the meeting go between Gagnon and John Paul I?

Gagnon met with the new pontiff, Pope John Paul I, and—as advised by Benelli

(as if he needed advising)—Gagnon took with him the completed study of his

investigation and a much-redacted dossier thereof. That redacted version

consisted of several typewritten pages of urgently needed changes in the Roman

Curia; some long overdue transfers, and some new, strongly suggested

appointments. Gagnon left the papal audience completely satisfied. “He will

act quickly,” he told me. I can still see his face; there was no smile on it.

Rather, after making that matter-of-fact statement, he concluded with the

word: “Done.” His expression was stonelike, serious. After three years of

intense and challenging work, dangerous interviews, room and office break-ins

and physical threats to his life, Edouard Gagnon had accomplished what by

papal decree he had been commissioned to do. Change, much and desperately

needed change was about to come to the Church, to the People of God—like rain

to a parched earth.

So there was some hope and enthusiasm over what was to come of the

visitation’s report to the new Holy Father?

To be sure. Later that night, the three of us [Gagnon, Marini, and me] went to

dinner at Lo Scarpone and, as always, we took our far-in-the-corner table

where we could speak more freely. Marini was elated with Edouard Gagnon’s

description of the papal briefing on the visitation—that is, with what Gagnon

felt he was able to share. And though Gagnon did not come right out and say

it, we knew that Giovanni Benelli was on his way back to Rome to take control

of the Secretariat of State. Personally speaking, I felt that the years of

uncertainty [1965–1978] were over. There would finally be a straightforward,

Catholic direction in the Church. John Paul I and Benelli might even become a

second Sarto/Merry del Val team!

But it wasn’t meant to be. Pope John Paul I died shortly after his election

and was succeeded by Karol Wojtyła, Pope John Paul II. Did Gagnon also speak

with John Paul II about the report? If so, what happened at this time?

Indeed, Gagnon did speak with Pope John Paul II. Pope John Paul II summoned

Archbishop Gagnon to a private audience in October of 1978 to discuss the

results of the Papal Visitation to the Roman Curia. In that October meeting,

Archbishop Gagnon detected much less enthusiasm on the part of the new

pontiff. John Paul II was already preparing to travel. To Mexico, if I’m not

mistaken. And, like his rather imprudent, very short-lived predecessor, the

new pope also reconfirmed every member of the Roman Curia in his

position—first and foremost, Secretary of State, Jean Cardinal Villot. Suffice

it to say, reforming the Roman Curia was the furthest thing from the Polish

pope’s mind.

How exactly did Gagnon advise John Paul II to act?

Based on the results of his investigation, Gagnon urgently insisted that the

pope: 1) remove Sebastian Cardinal Baggio from his position as Prefect for the

Sacred Congregation for Bishops and replace him with a strong and believing

Catholic who would give the Catholic Church the good bishops she so urgently

required, 2) remove and replace Cardinal Jean Villot as Secretary of State, 3)

remove and replace Bishop Paul Marcinkus as President of the

Instituto per le Opere di Religione [i.e., the Vatican Bank]. Gagnon

warned him that if drastic measures were not taken to reform the Church’s

central government, he, the pope, would be responsible and would greatly

suffer the consequences. Gagnon relayed this stern warning to the pope, “Not

to act swiftly and decisively, Holy Father, will cause much more harm to the

Church—and could cost you your life, as well.”

Given how the events of the Holy Father’s life later played out with the

1981 assassination attempt, that last warning is especially grave. What was

John Paul II’s response to these warnings and recommendations in 1978?

He did not disagree with the recommendations, but he did not see the urgency

of implementing them so soon. Besides, the new pope had already decided on a

new direction, a new role for the papacy. He himself, the Vicar of Christ on

earth, would carry Christ’s Gospel to the ends of the earth, to a world much

in need of the Good News. This was Pope John Paul II’s goal; not the

reform of the Church’s government. Naturally, every member of the Roman

Curia—above all, Jean Villot, Sebastiano Baggio and Paul Marcinkus—were elated

with the Polish pope’s fresh evangelical ideals! Practically every member of

the Roman Curia applauded the announcement of every new trip! And, of course,

the mice played and played while the cat remained away, and further and

further away!

Your observation here has grave repercussions for many things, such as the

composition of the Church’s Pastors throughout the world. With someone like

Baggio selecting the bishops, would you think it fair to say that there were

some questionable characters that were put into positions of authority?

You’d be very safe in assuming more than a few “questionable characters” made

it to positions of ecclesiatical authority, back then. And remember: they are

bishops for life. As Marini used to remind us: “Whether heaven or hell be

their final destination, they will be in heaven or hell, for all eternity, as

bishops.”

How did Gagnon respond to the Holy Father’s reaction?

Let me start by saying that Archbishop Edouard Gagnon was a scholar and a

saint; a lawyer, a theologian, a practical and no-nonsense man and, most

importantly, nobody’s fool. The morning after Gagnon’s private audience with

John Paul II, I accompanied him to Cortile San Damaso at the Vatican. Gagnon

waited in the car and sent me upstairs to the Secretariat of State. I was to

hand-deliver his resignation from all things Vatican to the pope, through his

reconfirmed Secretary of State, Jean Cardinal Villot. To put it mildly, when

Villot finished reading the short but not-so-sweet missive, he was outraged.

One does not simply “resign” from a papal appointment in the Vatican; protocol

forbade it; it was unheard of. Villot insisted that Gagnon present himself in

the Secretariat immediately. I informed the Secretary of State that the

archbishop would not, and bid him a good day. I returned to the car and drove

Archbishop Gagnon straight to Leonardo Da Vinci Airport. He left Rome, intent

on never returning. His fervent desire was to return to Columbia and—holy

priest that he was—to recommence his work there among the poor.

Two and a half years later, May 13, 1981, was the assassination

attempt on John Paul II’s life. Was this attempt connected to Gagnon’s

warning to the Holy Father back in 1978? If so, what did John Paul II do now

that Gagnon’s warning had come to pass?

Yes, it was connected to Gagnon’s warning to the pope—and that certainly seems

to be how the pope himself took it. Mind you, I wasn’t there to hear this with

my own two ears, but it was reported by many people in the know that from his

Clinica Gemelli hospital bed, when he regained consciousness, Pope John Paul

II’s first words to his private secretary, Msgr. Stanisław Dziwisz, were:

“...find Gagnon.” The word went out and the search for Gagnon was on. It was

Cardinal Casaroli who finally located Archbishop Gagnon and communicated the

Holy Father’s expressed desire that he return to Rome at once and take up some

very unsettled matters.

Except to say that Gagnon obeyed the pope, returned to Rome, and was made a

cardinal, I don’t wish to comment any further on the matter. I will save that

commentary and a few more surprising revelations for my upcoming novel, the

working title of which is Of Rats and Men. I will say this much now:

only after the May 13, 1981 assasination attempt did the Polish Pontiff call

Giovanni Benelli to be his right-hand as Secretary of State. Benelli died of a

massive heart attack two weeks prior to beginning that new job. Another Roman

“mystery.”

Do you mean to imply that there was something suspicious about Benelli’s

death?

I mean to say that I find it highly suspect for a healthy, sixty-one-year-old

powerhouse of a man like Giovanni Cardinal Benelli to suddenly drop dead of a

heart attack just days after agreeing to become Pope John Paul II’s new

Secretary of State, and just days before actually tackling the tremendous

challenge of restoring order to an out-of-control Church. I’m saying that I

consider it highly suspect that that same man, Giovanni Cardinal Benelli—whose

first and foremost piece of business as Secretary of State would most

assuredly have been the unceremonious removal of Sebastian Cardinal Baggio

from the Congregation for Bishops—should die before his first Roman day on the

job.

You mentioned Paul Marcinkus earlier. There are some ambiguities

surrounding him. He is sometimes referred to as Paul VI’s “unofficial

bodyguard” who thwarted an assasination attempt on Paul VI’s life in Manila,

Philippines in 1970. Later, Marcinkus was under indictment by the Italian

Supreme Court for some financial shenanigans. Interestingly enough, when the

statute of limitations ran out, he happened to show up leaving Vatican City.

Do you have any knowledge of this matter?

Everyone I knew in Vatican circles considered Paul Marcinkus—how shall I put

this?—not a man of extraordinary intellect. In fact, he was seen as the

epitome of American naïveté. At the risk of sounding exaggerated, permit me to

describe the brief 1975 meeting between Marcinkus and my dear avuncular

friend, John S. Lloyd, City Attorney of Miami, Florida.

I accompanied Lloyd to Marcinkus’ office in the “Vatican Bank” and knocked on

his half-opened office door. I could hear that the episcopal bank-president

was in the middle of a phone call; nonetheless, he called out a loud “Avanti!”

for us to enter. When I opened the door fully, he waved us in and pointed that

we should take to the two chairs facing his desk. Marcinkus continued his

English conversation. The big man was dressed in a black suit and Roman

collar; his two feet crossed at the ankles and resting on the desktop; a lit

cigar in his right hand. He was Yankee Imperialism. Frankly, I was embarrassed

that John Lloyd, a convert to the Faith, had a front row/center seat to such a

ridiculous, cartoonish, bombastic display of crass Americana. I couldn’t get

out of there fast enough.

Marcinkus was the Yankee fool that the Italian Freemasons, with the greatest

of ease and very little flattery, took for a ride. When it was finally

discovered just how he had been played and utilized by

Propaganda Due—the Freemason Lodge that orchestrated the Vatican Bank

scandal—Marcinkus remained inside the Vatican walls to escape Italian prison

walls. During his confinement, he lamented that, deprived of a golf course,

his game was bound to suffer. The point is, Bishop Paul Marcinkus was

considered far more foolish than evil. Villot and Baggio, who supported and

(when attacked) defended Marcinkus as president of the bank, knew much better

than he what the endgame was. For all intents and purposes, Marcinkus was—as

they say today—“clueless.”

Within this drama you have laid out here, Fr. Murr, decisions were

made that have had a lasting effect upon the average layperson in the

pews. Many have tried to make sense of everything, and, as you point out

in The Godmother, they have gone to various extremes that offer answers but which are

ultimately unfulfilling. What would you say to the average layperson

trying to make sense of the malaise and desolation that has happened in

the Church over the past 50 or so years?

As difficult—perhaps even as “impossible”—as this may sound: these present

times call for the Catholic faithful, the laity, to know and love Jesus Christ

and His Church extraordinarily well, and to become even more outstanding men

and women of prayer. To those who, in great numbers, are finally waking up to

the harsh reality of what has been plaguing our Church for half a century and

continues, with diabolical force, to plague her today, I say: be strong and

stay the course. We are in the battle of our lives and what is at

stake is the salvation of our own souls and the very soul of humanity.

Fr. Murr, there is one final question for you as we end this interview. Why

do you feel that it is important to make all of these revelations now?

The day that his Holiness, Pope Pius XII, died is etched forever in my memory.

In detail, I did my best to describe that day in the opening chapter of

The Godmother. I was even awarded the singular grace to locate Sister

Mary Wilberta, O.P., my first and second grade teacher, and discuss the

details of our “sacrosanct conversation” that day. As I hoped she would, even

after sixty years she remembered it clearly and with great fondness... What a

very special gift. Deo gratias.

But there was one final thought that came to me that October day in 1958—or

rather, that came to me that October night just before I fell asleep. I

remember thinking: “If that [death] could happen to the Holy Father, the pope

of Rome—with the entire world praying for him—it very likely could happen to

me, as well!!” What I strongly suspected could happen, even to me,

back in 1958, at age eight, I am now convinced, in 2020, at age seventy,

will happen to me—and much sooner rather than later!

Before I go to God, I want those who will be trying to understand the

aftermath of the Second Vatican Council (for generations to come) to know a

few things about some of the major players in those crucial times for the

Church and the world. I hope I have shed some light into a few dark corners.

[i]

In the previous interview, Fr. Murr misspoke. He reconciled with Msgr. Marini

in 2005, not 2009—KJS.