In comments published in The Tablet, newly-minted Cardinal Arthur Roche manages to utter what may well be the most ironic statement since Vatican II:

That reform [to Catholic worship since the Council] is taking place, but it’s a slow process because there are those who are dragging their feet with regard to this and not only dragging their feet but stubbornly opposing what the Church has actually decreed. That’s a very serious matter. In the end, people have to ask themselves: am I really a Catholic, or am I more of a Protestant?

Let’s think about this for a moment.

As Michael Davies demonstrated in his masterpiece Cranmer’s Godly Order: The Destruction of Catholicism through Liturgical Change, the liturgical reform after Vatican II—going far beyond the conciliar remit—emulated, in dozens of ways, the liturgical “reforms” fashioned by Cranmer and imposed on England by its rulers. The Book of Common Prayer was a revolution in the lex orandi so that it might reflect and promote a Protestant lex credendi.

For example, the Novus Ordo, like Cranmer’s missal, repudiates an oblative offertory, replacing it with a supper-oriented “presentation of gifts” based on the Jewish berakah, which does not unambiguously signify that the Mass is a true and proper sacrifice in propitiation for sins and for the good estate of the living and of the dead, offered to the Most Holy Trinity by the Son of God according to His human nature. As F. A. Gasquet and E. Bishop write:

The ancient ritual oblation, with the whole of which the idea of sacrifice was so intimately associated, was swept away. This was certainly in accord with Cranmer’s known opinions. . . . To understand the full import of the novelty it must be borne in mind that this ritual oblation had a place in all liturgies [of Christendom].[i]

It is worthy of note that Luther, when designing his own Order of Mass for his followers, omitted the Roman Offertory, which he called “that complete abomination into the service of which all that precedes in the Mass has been forced, whence it is called Offertorium, and on account of which nearly everything sounds and reeks of oblation.”[ii]

Not only Cranmer’s actions, then, but Luther’s theology also influenced the architects of the Novus Ordo. As Joseph Ratzinger observed in his lecture “Theology of the Liturgy” given at Fontgombault in July 2001:

Who still talks today about “the divine Sacrifice of the Eucharist”?... Stefan Orth, in the vast panorama of a bibliography of recent works devoted to the theme of sacrifice, believed he could make the following statement as a summary of his research: "In fact, many Catholics themselves today ratify the verdict and the conclusions of Martin Luther, who says that to speak of sacrifice is ‘the greatest and most appalling horror’ and a ‘damnable impiety’: this is why we want to refrain from all that smacks of sacrifice, including the whole canon, and retain only that which is pure and holy.” Then Orth adds: “This maxim was also followed in the Catholic Church after Vatican II, or at least tended to be, and led people to think of divine worship chiefly in terms of the feast of the Passover related in the accounts of the Last Supper.” [In this connection see José Ureta’s illuminating critique of Francis’s Desiderio Desideravi.—PK]…A sizable party of Catholic liturgists seems to have practically arrived at the conclusion that Luther, rather than Trent, was substantially right in the sixteenth century debate; one can detect much the same position in the postconciliar discussions on the Priesthood. The great historian of the Council of Trent, Hubert Jedin, pointed this out in 1975, in the preface to the last volume of his history of the Council of Trent: “The attentive reader…in reading this will not be less dismayed than the author, when he realizes that many of the things—in fact almost everything—that disturbed the men of the past is being put forward anew today.” It is only against this background of the effective denial of the authority of Trent, that the bitterness of the struggle against allowing the celebration of Mass according to the 1962 Missal, after the liturgical reform, can be understood. The possibility of so celebrating constitutes the strongest, and thus (for them) the most intolerable contradiction of the opinion of those who believe that the faith in the Eucharist formulated by Trent has lost its value….Meßner’s certainly respectable work on the reform of the Mass carried out by Martin Luther, and on the Eucharist in the early Church, which contains many interesting ideas, arrives nonetheless at the conclusion that the early Church was better understood by Luther than by the Council of Trent.[iii]

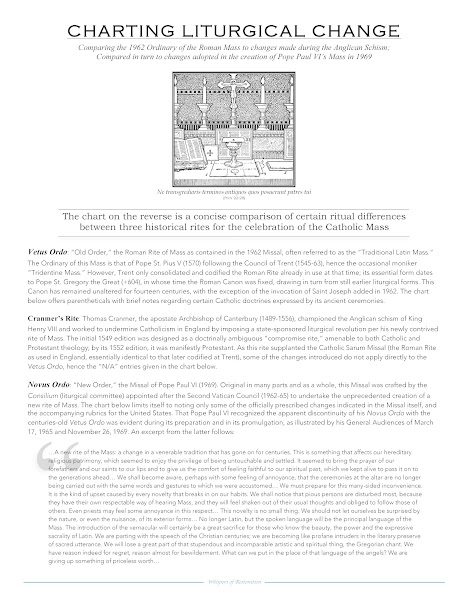

The view that the early Christian Mass was more “authentic,” more in keeping with what Jesus intended—free from all the medieval clutter, repetition, bowing and scraping, pious mumbo-jumbo, devotionalism, and even superstition that grew up around it later—is precisely the view that unites the original Protestants with their latter-day descendents in the radical wing of the Liturgical Movement that produced the Novus Ordo. I discuss this point at length in my forthcoming book The Once and Future Roman Rite: Returning to the Latin Liturgical Tradition after Seventy Years of Exile, as well as in a couple of articles online (here and here); but it will suffice to provide a picture-perfect example of such antiquarian reformism that I stumbled across only recently:

The liturgy we experience today is quite different from that of fifty or sixty years ago. Over the ages, what began as a gathering of friends and followers of Jesus sharing a meal and remembering his teachings became an increasingly elaborate ceremony of sacrifice. The celebrations of the Lord’s Supper, held in secret in people’s homes during the times of persecution, gave way to highly ritualized ceremonies held in beautiful churches. By the Middle Ages, the priest was saying Mass while the people watched in silence. The focus was primarily on Jesus’ sacrifice, which diminished the symbol of a shared meal. Those attending were not participants as much as watchers. In the 1960s the bishop from around the world gathered at the Second Vatican Council. They called for important reforms to renew the liturgy. The language of the liturgy changed from Latin to the vernacular, so that for the first time in hundreds of years, the people could hear and understand the prayers being said. People were also encouraged to receive Communion, in the hand, and from the cup. The idea of a shared meal around a table was reclaimed from the early years of Christianity.

This is taken from a middle-school Religious Ed textbook: Catholic Faith Handbook for Youth, published by Saint Mary’s Press in 2008. It even has the nihil obstat and imprimatur! (The devaluation of Catholic currency on full display.) It is precisely this “quite different experience” of liturgy that not only prompted a mass exodus of Catholics after the Council but also, and more damningly still, led to the well-documented erosion of faith in the Real Presence, of awareness of moral conditions for receiving the Eucharist (including recourse to Confession), of the Sunday obligation, and so forth. The past fifty years have offered an unanswerable demonstration—if anyone needed convincing—of the ironclad axiom lex orandi, lex credendi.

Nor should we be surprised by these Protestant/Novus Ordo parallels. An explicit intention of the modern Catholic liturgical reforms was an ecumenism designed to bring Catholics and Protestants together. As Annibale Bugnini famously wrote in the March 19, 1965, edition of L’Osservatore Romano, concerning the softening of the prayer for the conversion of heretics and schismatics on Good Friday:

[L]et’s say that often the work [of the Consilium’s ongoing editing of prayers] proceeded “with fear and trembling” by sacrificing terms and concepts so dear, and now part of the long family tradition. How not to regret that “Mother Church—Holy, Catholic and Apostolic—deigned to revoke” the seventh prayer? And yet the love of souls and the desire to help in any way the road to union for the separated brethren, by removing every stone that could even remotely constitute an obstacle or source of difficulty, have driven the Church to make even these painful sacrifices.[iv]

This interpretation is confirmed not only by the oft-mentioned participation of six Protestants in the Consilium that worked on the new liturgy (their role was mainly confined to the new Lectionary[v]) but even more by the testimony of a close personal friend of Paul VI, the philosopher Jean Guitton:

First of all, Paul VI’s Mass is presented as a banquet, and emphasizes much more the participatory aspect of a banquet and much less the notion of sacrifice, of a ritual sacrifice before God with the priest showing only his back. So, I don’t think I’m mistaken in saying that the intention of Paul VI and the new liturgy that bears his name is to ask of the faithful a greater participation at Mass; it is to make more room for Scripture, and less room for all that is, some would say magical, others, transubstantial consecration, which is the Catholic faith. In other words, there was with Paul VI an ecumenical intention to remove, or at least to correct or to relax what was too Catholic, in the traditional sense, in the Mass, and, I repeat, to bring the Catholic Mass closer to the Calvinist Mass.[vi]

Cranmer… Luther… Calvin… “That’s a very serious matter. In the end, people have to ask themselves: am I really a Catholic, or am I more of a Protestant?”

I have a piece of advice for Cardinal Roche’s friends and associates. They should tell him to stop speaking and especially to stop giving interviews. Every time he opens his mouth, he promotes the cause of Tradition. In this respect, he imitates to perfection the one who created him cardinal.

|

| Then-bishop Arthur Roche, with Card. Cormac Murphy-O'Connor and “Archbishop” Rowan Williams (Photo: Mazur/catholicchurch.org.uk) |

NOTES

[i] Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer (London: John Hodges, 1891), 196. Gregory DiPippo has demonstrated exhaustively that every liturgical rite, for long before the Council of Trent, concurred in having just such a proleptic oblative offertory. Go here for a list of some of the many articles he has published on the subject, including refutations of modern liturgists.

[ii] See Martin Luther, Formula missae et communionis pro ecclesia Wittembergensis (1523), in Works of Martin Luther, vol. 6 (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1932), 88. A description of Luther’s plan for Mass and his reasoning about what to keep and what to reject is found in Gasquet and Bishop, Edward VI, 220–24.

[iii] See “The Theology of the Liturgy,” in Theology of the Liturgy: The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence (Collected Works of Joseph Ratzinger, vol. 11), ed. Michael J. Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), 541–57; cf. 207–17. See also Michael Davies, Pope Paul’s New Mass (Kansas City, MO: Angelus Press, 2009), 329–47.

[iv] This quotation came under renewed discussion because the Mass of the Ages Episode II misquoted it as if it referred to the entire Mass rather than to the prayer of Good Friday. The Mass of the Ages issued an official apology and correction. Yet as Gregory DiPippo pointed out: “The statement is nevertheless a fair summary of the ethos of the reform as a whole. The reformers unquestionably saw their mission not as the restoration of the liturgy which the Council had asked for, but the remaking of it in their own image and likeness. Ferdinando Cardinal Antonelli, who was a member of the Consilium, and in principle very much in favor of reform, stated this outright in his memoirs. And furthermore, this remaking did unquestionably consist in the reformers identifying, each according to his own personal ideas, what in the liturgy constituted an ‘obstacle,’ whether it be to the comprehension of the faithful, ecumenical progress, or some other hazily identified but unquestionably desirable goal, and taking it out. And this is why they took advantage of the highly imprudent ambiguity of Sacrosanctum Concilium’s statement that ‘elements which…were added (to the liturgy) with but little advantage are now to be discarded,’ and discarded any number of elements that are attested in every single pertinent liturgical book of the Roman Rite as far back as we have them.”

[v] The new Lectionary, which we have been taught to think of as the most obvious positive fruit of the reform, is in fact a masterpiece of illusion and misguidance. See this video for a general critique of the reconfiguration and content of the “Liturgy of the Word”; my lecture “Mythbusting: Why the Traditional Latin Mass’s Lectionary Is Superior to the New Lectionary”; and my essay “Not Just More Scripture, But Different Scripture.” Every week, one sees posts on Facebook and Twitter of Catholics who have discovered for themselves how artfully (shall we say) the Word of God is edited and manipulated by the reformers' lectionary.

[vi] Yves Chiron, with François-Georges Dreyfus and Jean Guitton, “Entretien sur Paul VI” (Niherne: Éditions Nivoit, 2011), 27–28, provided by Sharon Kabel in “Catholic fact check: Jean Guitton, Pope Paul VI, and the liturgical reforms”; translation mine. Just how close a friend Paul VI considered Guitton may be inferred from the fact that (1) the former asked the latter to suggest ideas for his inaugural encyclical; (2) a couple of years later, asked him, along with Jacques Maritain, to draft the various “messages” that the pope would deliver at the end of the Second Vatican Council; and (3) he hosted him annually at the Vatican on September 8, which was the date they first met in 1950. See Yves Chiron, Paul VI: The Divided Pope, trans. James Walther (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2022), 117, 188, 215. Bishop Athanasius Schneider points out another way in which Calvinism influenced the liturgical reform:

[ii] See Martin Luther, Formula missae et communionis pro ecclesia Wittembergensis (1523), in Works of Martin Luther, vol. 6 (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1932), 88. A description of Luther’s plan for Mass and his reasoning about what to keep and what to reject is found in Gasquet and Bishop, Edward VI, 220–24.

[iii] See “The Theology of the Liturgy,” in Theology of the Liturgy: The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence (Collected Works of Joseph Ratzinger, vol. 11), ed. Michael J. Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), 541–57; cf. 207–17. See also Michael Davies, Pope Paul’s New Mass (Kansas City, MO: Angelus Press, 2009), 329–47.

[iv] This quotation came under renewed discussion because the Mass of the Ages Episode II misquoted it as if it referred to the entire Mass rather than to the prayer of Good Friday. The Mass of the Ages issued an official apology and correction. Yet as Gregory DiPippo pointed out: “The statement is nevertheless a fair summary of the ethos of the reform as a whole. The reformers unquestionably saw their mission not as the restoration of the liturgy which the Council had asked for, but the remaking of it in their own image and likeness. Ferdinando Cardinal Antonelli, who was a member of the Consilium, and in principle very much in favor of reform, stated this outright in his memoirs. And furthermore, this remaking did unquestionably consist in the reformers identifying, each according to his own personal ideas, what in the liturgy constituted an ‘obstacle,’ whether it be to the comprehension of the faithful, ecumenical progress, or some other hazily identified but unquestionably desirable goal, and taking it out. And this is why they took advantage of the highly imprudent ambiguity of Sacrosanctum Concilium’s statement that ‘elements which…were added (to the liturgy) with but little advantage are now to be discarded,’ and discarded any number of elements that are attested in every single pertinent liturgical book of the Roman Rite as far back as we have them.”

[v] The new Lectionary, which we have been taught to think of as the most obvious positive fruit of the reform, is in fact a masterpiece of illusion and misguidance. See this video for a general critique of the reconfiguration and content of the “Liturgy of the Word”; my lecture “Mythbusting: Why the Traditional Latin Mass’s Lectionary Is Superior to the New Lectionary”; and my essay “Not Just More Scripture, But Different Scripture.” Every week, one sees posts on Facebook and Twitter of Catholics who have discovered for themselves how artfully (shall we say) the Word of God is edited and manipulated by the reformers' lectionary.

[vi] Yves Chiron, with François-Georges Dreyfus and Jean Guitton, “Entretien sur Paul VI” (Niherne: Éditions Nivoit, 2011), 27–28, provided by Sharon Kabel in “Catholic fact check: Jean Guitton, Pope Paul VI, and the liturgical reforms”; translation mine. Just how close a friend Paul VI considered Guitton may be inferred from the fact that (1) the former asked the latter to suggest ideas for his inaugural encyclical; (2) a couple of years later, asked him, along with Jacques Maritain, to draft the various “messages” that the pope would deliver at the end of the Second Vatican Council; and (3) he hosted him annually at the Vatican on September 8, which was the date they first met in 1950. See Yves Chiron, Paul VI: The Divided Pope, trans. James Walther (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2022), 117, 188, 215. Bishop Athanasius Schneider points out another way in which Calvinism influenced the liturgical reform:

[T]oday the faithful take and touch the Host directly with their fingers and then put the Host in the mouth: this gesture has never been known in the entire history of the Catholic Church but was invented by Calvin — not even by Martin Luther. The Lutherans have typically received the Eucharist kneeling and on the tongue, although of course they do not have the Real Presence because they do not have a valid priesthood. The Calvinists and other Protestant free churches, who do not believe at all in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, invented a rite which is void of almost all gestures of sacredness and of exterior adoration, i.e., receiving “Communion” standing upright, and touching the bread “host” with their fingers and putting it in their mouth in the way people treat ordinary bread.…

For them, this was just a symbol, so their exterior behavior towards Communion was similar to behavior towards a symbol. During the Second Vatican Council, Catholic Modernists—especially in the Netherlands—took this Calvinist Communion rite and wrongly attributed it to the Early Church, in order to spread it more easily throughout the Church. We have to dismantle this myth and these insidious tactics, which started in the Catholic Church more than fifty years ago, and which like an avalanche have now rolled through, crushing almost all Catholic churches in the entire world, with the exception of some Catholic countries in Eastern Europe and a few places in Asia and Africa. (Christus Vincit, 223–24; right before this, Bp. Schneider explains how the Calvinist communion method differs from the one described by St. Cyril of Jerusalem)