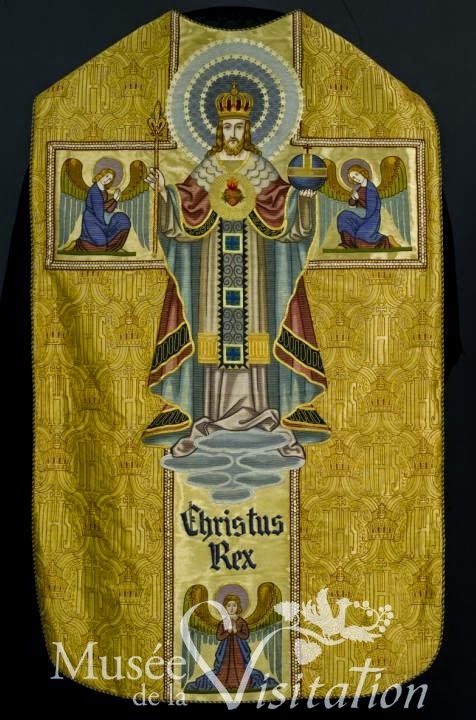

On the one hand, it is wonderful that the liturgical art of Western Europe, in particular post-revolutionary France and especially in textiles, is preserved rigorously by the Order of the Visitation (the Visitandines, the order founded by St. Jane de Chantal, whose most famous saint is St. Margaret Mary Alacoque) in their museum in Moulins, right in the middle of France.

On the other, it is sad to see most of these pieces not put into the use for which they were intended. They are beautiful, but most are not ancient, there is no reason why they should be simply put aside -- institutes of priests dedicated to the Traditional Mass would make good use of them.

Sadder of course is the fact that, with the consequences of the Second Vatican Council, a whole tradition (in the truest sense of the word, that is, a bundle of knowledge and expertise handed from one generation to the next one) of dedication of liturgical beauty was lost in the order, something that not even the French Revolution had been able to accomplish. These objects display immense skill and are an important part of the heritage of Western religious art -- and for this alone they ought to be preserved -- but they were made to be used, not merely admired, and outside of liturgical use they look mostly superfluous and in certain cases even vain.

Anyway, several pictures are available in the Museum of the Visitation's website (also in English), and they are currently holding a temporary exhibition dedicated specifically to 19th and 20th-century (first half) liturgical embroidery done in an almost industrial scale by many different religious houses and other makers. It was an unsurpassed period for liturgical art in one very important sense: the advent of different kinds of machines and technologies (such as the precision of colors provided by the nascent chemical industry and more uniform textiles) allowed for beautiful pieces for the first time to be relatively less expensive and widely available and viewed in even the neediest parishes and chapels. Regardless of the condescending view of some experts in the past (and also today), exponents of a pernicious and anti-popular elitism that also manifested itself in the attempted and nearly-accomplished destruction of ancient rite itself by committee-work, this popularization of beauty was undoubtedly a good thing, and cherished by most Catholic faithful.

The exhibition (called "En tous points parfait", "Perfect in every point" -- meaning needlepoints) was recently visited by French public television network France3 - the video was the inspiration for this short post. The media presentation of the exhibition is also quite interesting (in French, but filled with images).

Like rare animal specimens, preserved in glass cages