|

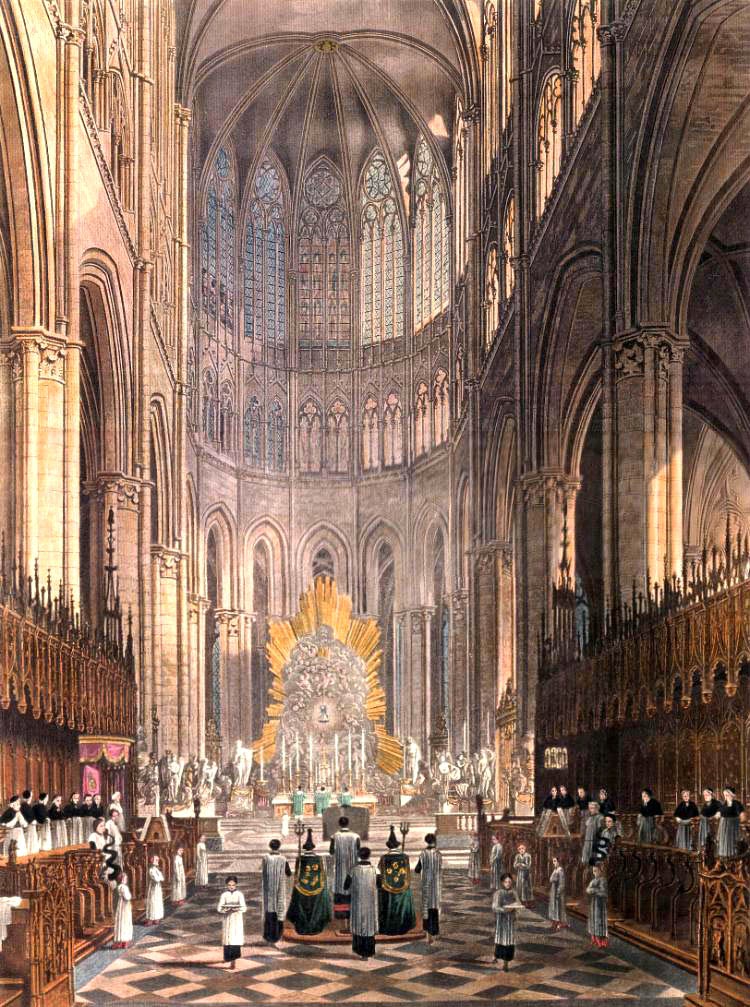

| Notre-Dame d'Amiens in the 19th century |

It is not a common event for a blog to publish a full translation of a great text of a major literary figure over one hundred years after its original publication, being able to claim it as a new event. Yet, this is just such a case.

On August 16, 1904, Marcel Proust had a major article published in the French paper of record, Le Figaro, called "La mort des cathédrales" (The Death of Cathedrals). The debate was raging in French political circles as Atheists and Freemasons, against the largely majoritarian sentiment of the population, pushed through Parliament the unilateral abrogation of the Napoleonic Concordat and the complete secularization of the French Republic (what would become the 1905 "Law of Separation" - for the appropriate Catholic view on the issues involved and its aftermath, read Saint Pius X's encyclicals on the issue, Vehementer Nos, Gravissimo officii, Une fois encore - and Pius XI's 1924 encyclical Maximam gravissimamque settling the matter). An important part of the debate was what exactly would happen to the upkeep and life of the highest point of French art and civilization, the Cathedrals.

Proust, an Agnostic in practice, but who never denied or stopped admiring his own Catholic roots and upbringing, could not stand in silence. Cathedrals as mere monuments, without the Traditional Catholic rites for which they were built, did not make any sense. What he could not know, the poor man, whose passion for the traditions and rites of the Church is palpable in the article, is that the Church herself would destroy and wipe out from most Cathedrals the venerable rites for which they were created. But, slowly and surely, they will return. As in Chartres in last year's ordinations for a traditional Fraternity. As in the occasional traditional Mass (such as the simple Mass celebrated each Sunday in that first Gothic jewel, Noyon). They will return.

Our deepest thanks to Prof. John Pepino for the remarkable translation of a landmark article, made especially for Rorate.

***

THE DEATH OF CATHEDRALS

Marcel Proust

Le Figaro

August 16, 1904

A Consequence Of the Briand Bill

On the Separation of Church and State

Suppose for a moment that Catholicism had been dead for centuries, that the traditions of its worship had been lost. Only the unspeaking and forlorn cathedrals remain; they have become unintelligible yet remain admirable.

Then suppose that one day scholars manage, on the basis of documentary evidence, to reconstitute the ceremonies that used to be celebrated in them, for which men had built them, which were their proper meaning and life, and without which they were now no more than a dead letter; and suppose that for one hour artists, beguiled by the dream of briefly giving back life to those great and now silent vessels, wished to restore the mysterious drama that once took place there amid chants and scents—in a word, that they were undertaking to do what the Félibres have done for ancient tragedies in the theatre of Orange.[1]

|

Notre-Dame de Chartres

|

Is there any government with the slightest concern for France’s artistic past that would not liberally subsidize so magnificent an undertaking? Do you not think that it would do what it did in the case of Roman ruins for these cathedrals, which are probably the highest, and unquestionably the most original expression of French genius? After all, one may well prefer the literature of other peoples to ours, prefer their music to ours, their painting and sculpture to ours, but it is in France that Gothic architecture created its first and most perfect masterpieces. All other countries have done is to imitate our religious architecture without ever matching it.

And so, to return to my hypothesis, here come scholars who have been able to rediscover the cathedrals’ lost meaning. Sculptures and stained-glass windows recover their significance, a mysterious odor once again wafts in the temple, a sacred drama is performed, and the cathedral starts to sing once more. When the government underwrites this resurrection, it is more in the right than when it underwrites the performances in the theaters of Orange, of the Opéra-Comique, and of the Opéra, for Catholic ceremonies have an historical, social, artistic, and musical interest whose beauty alone surpasses all that any artist has ever dreamed, and which Wagner alone was ever able to come close to, in Parsifal—and that by imitation.

Caravans of swells make their way to the holy city (whether it is Amiens, Chartres, Bourges, Laon, Rheims, Rouen, Paris, or whatever town you please, we have so many sublime cathedrals!), and once a year they experience the feeling they once sought in Bayreuth and in Orange: enjoying a work of art in the very setting that had been built for it. Alas, here as in Orange, they can only ever be curious dilettantes; try as they might, the soul of times past does not dwell within them. The artists who have come to perform the chants, the actors who play the role of priests may be learned, they may have imbued themselves with the spirit of the texts, and the Secretary of Education will lavish medals and compliments upon them. Yet, in spite of it all, one cannot help but think “Alas! How much more beautiful these feasts must have been when priests celebrated the liturgy not in order to give some idea of these ceremonies to an educated audience, but because they set the same faith in their efficacy as did the artists who sculpted the Last Judgment in the west porch tympanum or who painted the stained-glass lives of the saints in the apse. How much more deeply and truly expressive the entire work must have been when a whole people responded to the priest’s voice and fell to its knees as the bell rang at the elevation, not as cold and stylized extras in historical reconstructions, but because they too, like the priest, like the sculptor, believed. But alas, such things are as far from us as the pious enthusiasm of the Greeks at their theater performances, and our ‘reconstitutions’ cannot give a faithful idea of them.”

That is what one would say if the Catholic religion no longer existed and if scholars had been able to rediscover its rites, if artists had tried to bring them back for us. But the point is that it still does exist and has not changed, as it were, since the great century when the cathedrals were built. For us to imagine what a living and sublimely functioning thirteenth-century cathedral was like, we need not do with it as we do with the theater of Orange and turn it into a venue for exact yet frozen reconstitutions and retrospectives. All we need to do is to go into it at any hour of the day when a liturgical office is being celebrated. Here mimicry, psalmody, and chant are not entrusted to artists without “conviction.” It is the ministers of worship themselves who celebrate, not with an aesthetic outlook, but by faith—and thus all the more aesthetically. One could not hope for livelier and more sincere extras, since it is the faithful that take the trouble of unwittingly playing their role for us. One may say that thanks to the persistence of the same rites in the Catholic Church and also of Catholic belief in French hearts, cathedrals are not only the most beautiful monuments of our art, but also the only ones that still live their life fully and have remained true to the purpose for which they were built.

Now because of the French government’s break with Rome debates on Mr. Briand’s bill and its probable passing are imminent. Its provisions indicate that after five years churches may, and often will, be shut down; not only will the government no longer underwrite the celebration of ritual ceremonies in the churches, but will also be enabled to transform them into whatever it wishes: museums; conference centers, or casinos. As for you, Monsieur André Hallays! You go about repeating that works of art lose life as soon as they no longer serve the ends for which they were created, that furniture becomes so many knick-knacks and that a palace turned museum grows icy, can no longer speak to our heart, and ends up dying—I hope that you will stop for just one moment condemning the variously clumsy restorations that daily threaten the towns of France that you have taken into your care, and that you will rise to your feet, speak up, even harass Monsieur Chaumié if you have to, indict Monsieur de Monzie if need be, join Monsieur John Labusquière, and call a meeting of the Commission for Historical Monuments. Your clever zeal has often been effective; surely you will not let all the churches of France die in one fell swoop.

|

Notre-Dame de Paris

|

Today there is not one socialist endowed with taste who doesn’t deplore the mutilations the Revolution visited upon our cathedrals: so many shattered statues and stained-glass windows! Well: better to ransack a church than to decommission it. As mutilated as a church may be, so long as the Mass is celebrated there, it retains at least some life. Once a church is decommissioned it dies, and though as an historical monument it may be protected from scandalous uses, it is no more than a museum. One may say to churches what Jesus said to His disciples: “Except you eat the flesh of the Son of man, and drink his blood, you shall not have life in you” (Jn 6:54). These somewhat mysterious yet profound words become, with this new usage, an aesthetic and architectural axiom. When the sacrifice of Christ’s flesh and blood, the sacrifice of the Mass, is no longer celebrated in our churches, they will have no life left in them. Catholic liturgy and the architecture and sculpture of our cathedrals form a whole, for they stem from the same symbolism. It is a matter of common knowledge that in the cathedrals there is no sculpture, however secondary it may seem, that does not have its own symbolic value. If the statue of Christ at the Western entrance of the cathedral of Amiens rests on a pedestal of roses, lilies, and vines, it is because Christ said: “I am the rose of Saron”; “I am the lily of the valley”; “I am the true vine”.

If the asp and the basilisk, the lion and the dragon and sculpted beneath His feet it is because of the verse in Ps 90: Inculcabis super aspidem et leonem. To his left, in a small relief, a man is represented dropping his sword at the sight of an animal while a bird continues to sing beside him. This is because “the coward hasn’t the courage of a thrush”: indeed the mission of this bas-relief is to symbolize cowardice, as opposed to courage, because it is set under the statue that is always (at least in earliest times) to the right of the statue of Christ, that is, under the statue of St. Peter, the Apostle of courage.

And so it goes for the thousands of statues that adorn the cathedral.

Now the ceremonies involved in worship participate in the same symbolism. In an admirable book to which I should like eventually to pay a full tribute, Emile Male analyzes the first part of the feast of Holy Saturday according to William Durandus, Rational of the Divine Offices.

“Morning starts with all the lights being put out to indicate that the Old Law, which used to light up the world, is now abrogated.

Then the celebrant blesses the new fire, a figure of the New Law. He brings it out of the flint, to recall that Jesus Christ is, as Saint Paul says, the keystone of the world. At this point the bishop and the deacon make their way to the choir and stop before the Paschal candle.

William Durandus tells us that this candle is a threefold symbol. When it is unlit it symbolizes the dark pillar that guided the Hebrews by day, the Old Law, and the body of Jesus Christ. Once lit it signifies the pillar of light that Israel could see by night, the New Law, and the glorious body of the Risen Christ. The deacon alludes to this triple symbolism when he recites the Exultet before the candle.

But it is especially the resemblance between the candle and the Body of Jesus Christ that he emphasizes. He recalls that the spotless wax was produced by the bee, a creature both chaste and fruitful, like the Virgin who gave birth to the Saviour. To bring out to the sense of sight the likeness of the wax to the divine body, he presses five grains of incense into the candle; these recall both the five wounds of Jesus Christ and the spices that the Holy Women bought to embalm him. Lastly he lights the candle with the new fire and all lamps throughout the church are lit to represent the new Law in the world.

Someone will say: ‘But all this is only an exceptional feast.’ Here is the interpretation of a daily ceremony: the Mass. You will see that it is no less symbolic.

“The deep and sorrowful chant of the Introit opens the ceremony: it proclaims the expectation of the patriarchs and prophets. The clergy are in choir, the choir of the saints of the old Law who yearn for the coming of the Messias and do not see Him. Then the bishop enters and appears as the living image of Jesus Christ. His arrival symbolizes the Advent of the Lord that the nations await. On great feast days, seven torches are born before him to recall that, as the prophet says, the seven gifts of the Holy Ghost rest upon the head of the Son of God. He processes under a triumphant canopy whose four bearers may be likened to the four Evangelists. Two acolytes walk to this right and left and represent Moses and Elias, who appeared at Mount Tabor on either side of Christ. They teach that Jesus held the authority of the Law and of the Prophets.

The bishop sits on this throne and remains silent. He seems to take no part in the first part of the ceremony. His behavior contains a teaching: his silence recalls that the first years of the life of Christ were unknown and recollected. Meanwhile the subdeacon reaches the pulpit and reads the Epistle aloud towards the right. Here we catch a glimpse of the first act in the drama of our Redemption.

This reading of the Epistle is the preaching of Saint John the Baptist in the desert. He speaks before the Saviour has begun to make Himself heard, but he speaks only to the Jews. For this reason, the subdeacon, an image of the Precursor, turns to the North, the direction of the Old Law. Once the lesson is read, he bows before the bishop, just as the Precursor bowed before Jesus Christ.

The chanting of the Gradual follows the reading of the Epistle. It, too, refers to the mission of Saint John the Baptist: it symbolizes the exhortation to penance he directed towards the Jews on the eve of the new era.

At last the celebrant reads the Gospel. This is a solemn moment, for this is where the Messias’s active life begins: for the first time, His voice is heard in the world. The reading of the Gospel is the very figure of his preaching.

The creed follows the Gospel, just as the faith follows the proclamation of the truth. The twelve articles in the creed refer to the call of the Apostles.

“The very clothing the priest wears to the altar” and the objects used in worship amount to so many symbols, M. Male adds. “The chasuble, worn on top of the other garments, is charity, which is above all the commandments of the Law and is itself the supreme law. The stole, which the priest puts over his neck, is the light yoke of the Lord, and since it is written that every Christian must cherish this yoke, the priest kisses this yoke when he puts it on or takes it off. The bishop’s two-pointed miter symbolizes the knowledge he must have of each of the Testaments; two ribbons are attached to it to recall that Holy Scripture is to be interpreted both literally and spiritually. The bell is the voice of the preachers and the timber from which it hangs is a figure of the Cross. Its rope, woven from three twisted threads, points to the threefold understanding of scripture, which must be interpreted according to the threefold sense, i.e., historically, allegorically, and morally. When one takes the rope in hand to set the bell ringing, one symbolically expresses the fundamental truth that the knowledge of Scripture must lead to acts.”

And in this way everything down to the least of the priest’s gestures, down the stole he wears, comes together to symbolize Him with the deep sentiment that gives life to the whole cathedral and which is, as M. Male puts it so well, the genius of the Middle Ages itself.

Never has a sight comparable to such a giant mirror of knowledge, of the soul, and of history as this been presented to man’s eyes and understanding. The same symbolism clutters even the music heard in the immense vessel. Its seven Gregorian tones are the figure of the seven theological virtues and the seven ages of the world. One may well say that a production of Wagner at Bayreuth does not amount to much next to the celebration of High Mass at the Chartres cathedral.

Doubtless only those who have studied the religious art of the Middle Ages are able to analyze the beauty of such a spectacle fully. That alone would suffice for the State to have to see to its preservation. This is precisely how the State underwrites the lectures at the Collège de France, even though they are only intended for a small number of people and, if compared to the total resurrection of a Solemn Mass in a Cathedral, they seem like cold dissections; compared to the performance of such symphonies, the productions of our equally subsidized theaters answer to quite paltry literary demands. But let us hasten to add that the people who can read medieval symbolism fluently are not the only ones for whom the living cathedral, that is to say the sculpted, painted, singing cathedral is the greatest of spectacles, as one can feel music without knowing harmony. I am well aware that Ruskin, when he was demonstrating what spiritual reasons explain the arrangement of chapels in cathedral apses, declared: “Never will you be able to delight in architectural forms unless you are in sympathy with the thinking from which they arose.” Still, we all know the ignorant man, the simple dreamer, who walks into a cathedral without any effort at understanding yet is overwhelmed by his emotions and receives an impression which, though perhaps less precise, is certainly just as strong. As a literary witness to this state of mind, admittedly quite different to that of the learned person of whom we were speaking a moment ago and who walks in a cathedral “as in a forest of symbols who gaze on him with familiar glances,” yet which allows for a vague but powerful emotion in a cathedral during the liturgy, I shall quote Renan’s beautiful text The Double Prayer:

“One of the most beautiful religious spectacles one can still contemplate today (and which one may soon no longer be able to contemplate, if the House of Representatives passes the Briand bill) is that which the ancient cathedral of Quimper presents at dusk. Once darkness has filled the vast building’s side aisles, the faithful of both sexes gather in the nave and sing evensong in the Breton language with a simple and moving rhythm. The cathedral is lit only by two or three lamps. In the nave, the men are on one side, standing; on the other side, the kneeling women form a motionless sea of white headdresses. The two halves sing in alternation, and the phrase that one of the choirs begins is finished by the other. What they sing is quite beautiful. As I heard it, I felt that with a few changes it might be fitted to every state of humanity. Above all it made me dream of a prayer which, with a few variations, might suit men and women equally.

There are many gradations between between this reverie, which is not without its charm, and the religious art “connoisseur’s” more conscious joys. Let us bear and keep in mind the case of Gustave Flaubert, who studied—albeit with a view to interpreting it within a modern outlook—one of the most beautiful parts of the Catholic liturgy:

“The priest dipped his thumb in the holy oil and began to anoint his eyes first . . . then his nostrils, so fond of warm breezes and of the scents of love, his hands that had found their delight in sweet caresses . . . lastly his feet, which had been so swift in running to satisfy his desires, and which now would walk no more.”

There is therefore more than one way of dreaming before this artistic realization—the most complete ever, since all of the arts collaborated in it—of the greatest dream to which humanity ever rose; this mansion is grand enough for us all to find our place in. The cathedral, which shelters so many saints, patriarchs, prophets, apostles, kings, confessors, and martyrs that whole generations huddle in supplication and anxiety all the way to the porch entrances and, trembling, raise the edifice as a long groan under heaven while the angels smilingly lean over from the top of the galleries which, in the evening’s blue and rose incense and the morning’s blinding gold do seem to be “heaven’s balconies”—the cathedral, in its vastness, can grant asylum both to the man of letters and to the man of faith, to the vague dreamer as well as to the archeologist. All that matters is that it remain alive and that France should not find herself transformed overnight into a dried-up shore on which giant chiseled shells seem marooned, emptied of the life that once lived in them and no longer able even to give to an ear leaning in on them a distant rumor from long ago, mere museum pieces and icy museums themselves. “It is not too late,” André Hallays wrote some years ago, “to bring up a gruesome idea which, they say, was hatched in the brains of a few citizens of Vézelay. They wanted the church of Vézelay to be decommissioned. Such is the silliness that anticlericalism inspires. Decommissioning that basilica amounts to taking away what little soul it has left. Once the little lamp that shines deep in the sanctuary has been snuffed out, Vézelay will become no more than an archeological curiosity. The tomb-like odor of museums is all that will give breath in it.” Things keep their beauty and their life only by continuously carrying out the task for which they were intended, even should they slowly die at it. Does anyone believe that, in museums of comparative sculpture, the plaster casts of the famous sculpted wooden choir stalls of the Cathedral of Amiens can give an idea of the stalls themselves in their august yet still functional antiquity? Whereas a museum guard keeps us from getting too close to their plaster casts, the pricelessly precious stalls, which are so old, so illustrious, and so beautiful, continue to carry out their humble task in the cathedral of Amiens—which they have been doing for centuries to the great satisfaction of the citizens of Amiens—just as those artists who, while having become famous, yet still keep up a small job or give lessons. This task consists in bearing bodies even before they instruct souls, and that is what, folded down and showing their upper side, they humbly do during the offices. More than this: these stalls’ perpetually worn wood has slowly acquired, or rather let seep through, that dark purple that is so to speak its heart and which the eye that has once fallen prey to its charm prefers to everything else, to the point of being unable even to look at the colors of the paintings which, after this, seem rough and plain. Then one experiences something like ebriety as one savors, in the wood’s ever more blazing ardor, what is so to speak the tree’s sap overflowing in time. The naïf figures sculpted in it receive something like a twofold nature from the material in which they live. And generations have variously polished all of these Amiens-born fruits, flowers, leaves, and vegetation that the Amiens sculptor sculpted in Amiens wood, thus bringing out those wonderful contrasting tones in which the differently colored leaf stands out from the twig; this brings to mind the noble accents that Mr. Gallé has been able to draw out of the oak’s harmonious heart.

The cathedral, if Mr. Briand’s bill were passed, would not find itself closed and unable to provide the Mass and prayers just for the canons who perform the services in those stalls whose armrests, misericords, and banister tell of the Old and New Testaments, nor only for the people filling up the immense nave. We were just saying that nearly every image in a cathedral is a symbol. Yet some are not. Such are the painted or sculpted pictures of those who, having contributed their pennies to the decoration of the cathedral, wished to keep a place in it forever, so that they might silently follow the services and noiselessly participate in prayer from a niche’s balustrade or the recess of a stained glass window, in saecula saeculorum. we know that since the oxen of Laon had christianly drawn the construction materials for the cathedral up the hill from which it rises, the architect rewarded them by setting up their statues at the feet of the towers. You can see them to this day as, in the din of the bells and the pooling sunlight, they raise their horned heads above the colossal holy arch towards the horizon of the French plains—their “inner dream.” That was the best that could be done for beasts: for men, better was granted.

They went into the church. There they took their place, which would be theirs after death and from which, just as during their lifetime, they could go on following the divine sacrifice. In some cases, leaning out of their marble tomb, they turn their heads slightly to the Gospel or to the Epistle side and are able to glimpse and feel around them, as they can in Brou, the tight and tireless interlacing of crest flowers and initials; sometimes, as in Dijon, they keep even in their tombs the bright colors of life. In other cases, from the recess of a stained glass window, in their crimson, ultramarine, or azure cloaks that catch the sun and blaze up with it, they fill its transparent rays with color and suddenly let them loose, multicolored and aimlessly wandering in the nave, which they tinge with their wild and lazy splendor, with their palpable unreality. Thus they remain donors, who, for this very reason, have deserved perpetual prayers. And all of them want the Holy Ghost, when He will come down from the Church, really to recognize his own. It is not just the queen and the princes who wear their insignia, their crown, or their collar of the Golden fleece: money changers are portrayed proving the title of coins; furriers sell their furs (see Male for reproductions of those windows); butchers slaughter cows; knights wear their coat of arms; sculptors cut capitals. Oh! all of you in your stained glass windows in Chartres, in Tours, in Bourges, in Sens, in Auxerre, in Troyes, in Clermont-Ferrand, in Toulouse, ye coopers, furriers, grocers, pilgrims, laborers, armorers, weavers, stonemasons, butchers, basket makers, cobblers, money changers, o ye, great silent democracy, ye faithful obstinately wanting to hear the office, who are not dematerialized but more beautiful than in your living days now in the glory of heaven and blood that is your precious glass: no longer will you hear the Mass you had guaranteed for yourselves by donating the best part of your pennies to building this church. As the profound saying goes, the dead no longer govern the living. And the forgetful living stop fulfilling the wishes of the dead.

But let the ruby coopers and the rose and silver basket makers inscribe the backdrop of their stained glass with the “silent protest” that Mr. Jaurès could so eloquently give us and which we beg him to bring to the ears of the representatives. Leaving aside that innumerable and silent people, the ancestors of the electors for whom the House has such little concern, let us at last summarize:

First: safeguarding the most beautiful works of French architecture and sculpture, which will die on the day that they no longer serve the worship for which they were born, which is their function just as they are its organs, which explains them because it is their soul, makes it the government’s duty to demand that worship be offered in the cathedrals in perpetuity, while the Briand bill authorizes it to turn the cathedrals into whatever museums or conference halls (in the best of cases) it pleases after a few years, and even if the government does not undertake to do so, it authorizes the clergy (and, since it will no longer be subsidized, compels it) no longer to celebrate the offices in them if it finds the rent too high.

Second: the preservation of the greatest historic yet living artistic production imaginable, for the reconstruction of which, if it did not already exist, no one would shrink from spending millions, namely the cathedral Mass, makes it the government’s duty to subsidize the Catholic Church for the upkeep of a worship that is far more relevant to the conservation of the noblest French art (to continue our strictly worldly perspective) than the conservatories, theaters, concert-halls, ancient tragedy reconstitutions at the theater of Orange, etc. etc., all of which enterprises have doubtful artistic aims and which keep up many weak works (how do Le Jour, L’Aventurière, or Le Gendre de M. Poirier stand up to the choir of Beauvais or the statues of Rheims?), whereas the masterpiece that is the medieval cathedral, with its thousands of painted or sculpted figures, its chants, its services, is the noblest of all the works to which the genius of France has ever risen.

And so far in this article we have mentioned only the cathedrals, in order to present the consequences of the Briand bill in their most striking form, the form most apt to shock the reader’s mind. But obviously this distinction between cathedral churches and others is quite artificial, since it sufficed, on a feast day, to erect the bishop’s cathedra in a church to turn it into a cathedral for a day. What I have said about the cathedrals applies to all the beautiful churches of France, and it is a matter of common knowledge that there are thousands of them. On the French road “so beautiful” among sainfoin fields and apple orchards lining up on either side to let it through, with nearly every step you will see a steeple rising against stormy or peaceful horizons. On mixed days of rain and sun, it is set across a rainbow which, as a mystical halo reflected in the nearby heaven within the half-open church, juxtaposes its rich and distinct stained-glass colors on the sky. With nearly every step you see a steeple rising above the earth-gazing houses as an ideal, soaring amid the bell’s voices with which, if you come near, the birds’ song mingles. Well: you may often positively state that the church above which it rises contains beautiful and grave sculpted and painted thoughts, as well as other thoughts which, since they are not called to the same distinct life, have remained more vague, in a state of beautiful architectural lines that are more obscure yet also more powerful, as well as able to carry our imagination away in their upwards flight or to enclose it entirely within the curve of their pitch. There, from a Romanesque balcony’s charming bannisters or the mysterious threshold of a half-open Gothic porch that unites the sun, sleeping in the shade of the grand trees all around, to the church’s illumined obscurity within, we must go on to see the procession coming out of the multicolored shade falling from the stone trees of the nave and follow, as if in the countryside among the squat pillars and their flowery and fruited capitals, those paths regarding which one may say, as the prophet said of the Lord: “All of his paths are peace.” Finally, we have only mentioned an artistic interest in all of this. This is not to say that the Briand bill does not threaten other interests, or that we are indifferent to them. This, however, is the point of view we wanted to take. The clergy would be mistaken if it refused support from artists. For when one sees how many representatives, once they have finished passing anticlerical laws, go off on a tour of the cathedrals of England, of France, or of Italy, bring back an old chasuble for their wife to turn into a coat or a door-curtain, draw up secularization plans in offices where hangs a photographed version of the Entombment, haggle over an altar-piece volet with an antique dealer, go out into the countryside to fetch church stall fragments to serve as umbrella stands in their parlors, and, on Good Friday, “religiously”, as they say, listen to the Missa Papae Marcelli at the “Schola Cantorum” if not at Sainte-Geneviève, one may think that once we persuade all persons of good taste of the government’s duty to subsidize worship, we shall have found allies, and raised against the Briand bill, any number of representatives, even anticlerical ones.

Marcel Proust

_____________________________

[1] The first-century Roman theatre of Orange had been restored in the nineteenth century under the aegis of the Félibres, a Provençal cultural association. A yearly summer theatre festival (the “Chorégies”) started there in 1902, two years before this article.

[1] The first-century Roman theatre of Orange had been restored in the nineteenth century under the aegis of the Félibres, a Provençal cultural association. A yearly summer theatre festival (the “Chorégies”) started there in 1902, two years before this article.

[Exclusive full translation for Rorate by John Pepino, PhD. Please, mention translator, source, and link when mentioning it - partial translations available elsewhere. / Original posting time: Jan. 12, 9:30 am GMT]

[Jan. 14 Note: we were contacted about other translations: the present translation was completely made by Dr. Pepino at our request exclusively based on the original French text, published at Le Figaro (Thursday, August 16, 1904, edition, pages 3-4) and freely available at the Gallica digital library of periodicals of the Bibliothèque National de France. It has no relation whatsoever to any other translation, partial or otherwise, in English or in any other language, available elsewhere.]

[Jan. 14 Note: we were contacted about other translations: the present translation was completely made by Dr. Pepino at our request exclusively based on the original French text, published at Le Figaro (Thursday, August 16, 1904, edition, pages 3-4) and freely available at the Gallica digital library of periodicals of the Bibliothèque National de France. It has no relation whatsoever to any other translation, partial or otherwise, in English or in any other language, available elsewhere.]