The Burial of the Alleluia: A Poem by a monk from San Benedetto in Monte, Norcia, Italy

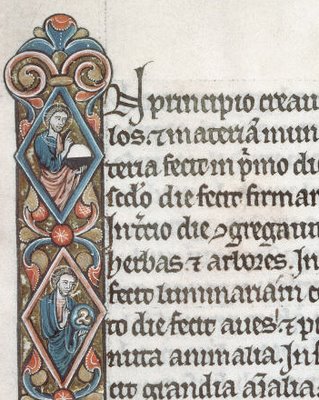

SEPTUAGESIMA: In the Beginning

The lessons for Matins introduce the theme of the penitential pre-lenten season of Septuagesima: Creation and Fall, and Original Sin; and God's intervention in History to purify mankind through a remnant in an ark (Sexagesima week) and to choose a People for himself; and the will of the unfathomable Divinity to reveal himself through his chosen people of Israel; and the Mystery of the Incarnation, through which the promise to Abraham ("in thee shall all the kindred of the earth be blessed", First Lesson in the Matins for Quinquagesima Sunday) would be fulfilled by the Divine Son of the Blessed Virgin ("I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel", Third Lesson in the Matins for Wednesday in Septuagesima week).

The reality of Original Sin ("I am the Immaculate Conception") and the great need for penitence in our times ("Penance! Penance! Penance!") were also the messages of the memorable events which began on February 11, 1858:

Cassocks, Tradition, and the Dying of the New Church of Vatican II

But one thing caught my eyes. The new priest was not only wearing a cassock, but also a sash. The uniform of a priest in the diocese of Bergamo may include a cassock,( but ..there are also priests who do not wear a cassock.) A small thing to point out, but still strange. In that it seems to fall in line with an excessive show of clerical solemnity that goes beyond what is required. I don’t want to make this a problem, but I can’t be enthusiastic about this. Because in the end one could think as follows: priests who are not serious wear lay clothes, priests who are somewhat serious wear clericals, priests who are really serious wear a cassock, and priests who are super-serious wear a sash. …On the day of his First Mass I would have rather have had an affirmation of fraternity than ardor for distinction.

Christopher Marlowe and the impossible desires of Faustus

In

the coming weeks Rorate will offer a series of short essays by Italian writer

Elizabetta Sala, commenting on some of the greatest English literary works of

all time, from the perspective of Traditional Catholicism. These include the works of C. Marlowe, Shakespeare, Milton, Joyce and

Tolkien as well as others.

Mrs.

Sala, a traditional Catholic, wife and mother of 7 children, is a Professor of

English History and Literature.

As a scholar of the History and Literature at the time of the English Reformation and expert on the works of William Shakespeare in particular, she is the author of several books* and is considered to be the foremost Italian authority on these subjects. As Antonio Socci says in a review (published by Rorate in September, 2019)**about her novel “The Execution :Of Justice” which treats of Shakespeare’s Catholicism: “[...]The writer, Elisabetta Sala, professor of English History and Literature reveals absolutely extraordinary narrative skills. In our present somewhat mediocre literary panorama, it is to be hoped that her talent is tested soon with other novels and that she becomes further and further known and recognized. Until now, Sala has been known [in Italy] as a most valiant scholar of the tragic age of Henry VIII and Elizabeth, at the time of “the rape” of the English people. [...]

*“The Wrath Of The

King Is Dead” [“L’ira del re è morte”(Ares)]

“Bloody Elizabeth”[“Elisabetta la sanguinaria”(Ares)].”The Enigma of Shakespeare” and her first novel “The Execution of

Justice”.

****

Here is the first short essay on Faustus by Christopher Marlowe.

Elizabetta Sala

Il Sussidiaro

January 2016

In 1589, the

Elizabethan Parliament enacted a law against theatre performances depicting

religious issues. It is very likely that the cause of this draconian decree was

the play Doctor Faustus by

Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) who had written it some months previously.

The audience of the

popular theaters was the most diverse imaginable and the task of every good

playwright was that of pleasing everyone. The story-line of Faustus was

certainly a great choice in this respect. But if the theme of the pact with the

devil, on the one hand, fascinated the audiences and ‘made a killing at the box-office’,

on the other, it stirred up issues that the authorities would have preferred

lay dormant.

Vatican Basilica: St. Peter's chapter considers banning Latin Mass and private side altar masses

Ever since at least the time of Constantine, when the persecution of Christians ended and the first Basilica on Vatican Hill, on top of the tomb of the Prince of the Apostles, was built, the highlight of the pilgrimage made by uncountable numbers of priests "ad limina apostolorum" has been the possibility of celebrating a personal private Mass at Saint Peter's. This has continued unabated even after the Novus Ordo.

Also, ever since at least the time of John Paul II (in the crypt), and more freely since Benedict XVI above ground, the Traditional Latin Mass has been celebrated privately in the Basilica.

But those venerable practices may be about to be abolished.

“Forgive Us, Father”: Join the Upcoming Eucharistic Reverence and Reparation Novena, January 24 to February 1, 2021

Ten Years of the Divinum Officium Project

Fr. Albert P. Marcello, III, J.C.D. (Cand.)

The number of textual resources for the liturgical books has grown considerably over the course of decades, with the impressive critical editions springing forth over the 20th century, as well as the liturgical studies done (at least in English) by such organizations as the Henry Bradshaw Society and others. Despite not being a textual critic, in the work of analyzing and systematizing such texts, credit must also be paid to the late Laszlo Kiss, a brilliant computer programmer who dedicated his retirement years to the project of ensuring that the texts of the Missal and Breviary would be available electronically, taking on the formidable task of translating the rubrics of these books into programming logic. With the generous support of Mr. Kiss’s family, especially his beloved wife, we at the Divinum Officium Project have attempted to humbly carry on this work.

Italian-American Weddings and the First Miracle of Jesus

We read in the second chapter of the Gospel of John: “Jesus performed this first of his signs at Cana in Galilee. Thus did he reveal his glory, and his disciples believed in him.” For me, when reading this account of the wedding feast at Cana: the question that comes to my mind is this: "Have you ever been to an Italian-American wedding?" Not an Italian wedding—something different yet similar but different—but an Italian-American wedding. Now I do not mean one of those toned-down, Americanized, rather staid affairs with pasta stations (imagine such a thing as a pasta station!), not these planned out affairs where the mother of the bride is out of place in her pastel lacy dress. The scene of today’s gospel is a Jewish wedding, and if the truth be known, and it is known, there are striking similarities between the ethnicity of Italians and Jews. Mothers and chicken soup. Matzoh balls and little meatballs. Need I say more.

"No Socialist system can be established without a Political Police: this would nip opinion in the bud, and stop criticism."

Insisting on the dialectical aspect of their materialism, the Communists claim that the conflict which carries the world towards its final synthesis can be accelerated by man. Hence they endeavor to sharpen the antagonisms which arise between the various classes of society. Thus the class struggle with its consequent violent hate and destruction takes on the aspects of a crusade for the progress of humanity. On the other hand, all other forces whatever, as long as they resist such systematic violence, must be annihilated as hostile to the human race. Communism, moreover, strips man of his liberty, robs human personality of all its dignity, and removes all the moral restraints that check the eruptions of blind impulse. There is no recognition of any right of the individual in his relations to the collectivity; no natural right is accorded to human personality, which is a mere cog-wheel in the Communist system.

...there can be no doubt that Socialism is inseparably interwoven with Totalitarianism and the abject worship of the State. …liberty, in all its forms is challenged by the fundamental conceptions of Socialism. …there is to be one State to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State is to be the arch-employer, the arch-planner, the arch-administrator and ruler, and the arch-caucus boss.

A Socialist State once thoroughly completed in all its details and aspects… could not afford opposition. Socialism is, in its essence, an attack upon the right of the ordinary man or woman to breathe freely without having a harsh, clumsy tyrannical hand clapped across their mouths and nostrils.

But I will go farther. I declare to you, from the bottom of my heart that no Socialist system can be established without a political police. Many of those who are advocating Socialism or voting Socialist today will be horrified at this idea. That is because they are shortsighted, that is because they do not see where their theories are leading them.

The Demographics of the Traditional Mass

The online theology journal Homiletic and Pastoral Review has published an article of mine drawing on the FIUV Report which discusses the demographic profile of Traditional Mass congregations.

I have demonstrated that the association between the EF and young people and families is neither a myth nor something limited to certain countries. Most Catholics have never encountered the EF, but of those who do, mostly by chance, the ones who make it their preferred Form of Mass are disproportionately young, and include a disproportionate number of families with small children. The presence of numerous children at the typical EF celebration can be confirmed, indeed, by anyone willing to set foot in one, provided it is celebrated in a reasonably family-friendly time and place, and is reasonably well-established.

The place of migrants, and in general of people of mixed cultural and linguistic backgrounds, at the EF, can be seen, naturally, only in places where the local population includes them. Nevertheless it is very evident in cities such as London, and as indicated in the statements quoted above, can be found in many countries.

Easiest of all to confirm is the presence of men at the EF. With Ordinary Form congregations in many places being increasingly dominated by older women, the ability of the EF to retain at least equal numbers of men, as well as young people and those bringing up children, is of no small significance.

De Mattei: True and False Conspiracies in History. In memory of Father Augustin Barruel (1741-1820)

Roberto de Mattei

Corrispondenza Romana

January 13, 2021

Among the anniversaries forgotten in 2020, was the bicentenary of the

death of Father Augustin Barruel, one of the top Counter-Revolutionary writers

of the 19th century.

Barruel was born in Villeneuve-de-Berg, France on October 2, 1741 and at

the age of sixteen he joined the Society of Jesus, which however, after being

banned in France, was suppressed in 1773 by Pope Clement XIV, under pressure

from the illuminist sovereigns. Barruel lived as a secular priest, in Paris,

where, between 1788 and 1792, he wrote Le

Helviennes ou lettres provinciales philosophiques (1781) against Rousseau

and Voltaire’s “philosophical party”, and directed the Journal ecclésiastique, a publication, in which, week after week,

he continued ceaselessly to denounce the responsibility of the Illuminists in

the French Revolution that had just broken out.

After the 1792 massacres, he was forced to go into hiding and then he emigrated

to London, where he wrote the Histoire du

clergé pendant la Révolution française (1793) e i Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire di jacobinisme (Fauche, 1798-1799).

This work was a great success, reprinted many times and translated into the

main European languages (the work was republished by La Diffusion de la Pensée Française, in 1974 and in 2013, with an

introduction by Christian Lagrave). In

1802, after the Church’s Concordat with Napoleon, Father Barruel, returned to

France, became Canon of Notre Dame Cathedral and in 1815, when the Society of

Jesus was re-established, he returned once again to his Order. He spent the

last years of his life in the community of Jesuits at Rue des Postes, in Paris,

where he died on October 5, 1820.

In the third and fourth parts of his Mémoires,

Barruel exposed the existence of a conspiracy against the thrones and altars by

the “Bavarian Illuminati”, a secret order founded in 1776 by Adam Weishaupt

(1748-1830), Professor of Canon Law at the University of Ingolstadt. Officially the

Illuminati proposed the moral perfection of its members, but the aim of

the sect, structured according to a strict gradualism, was a

Communist-style-social revolution. The social-anarchy program was revealed only

to the followers at the highest levels.

“The Dictatorship of Fear and the Coming Persecution” — Sermon by a Traditional Priest

Free 2021 traditional liturgical calendar for priests and bishops

As they have done the last few of years, the Servants of the Holy Family have asked us to alert the prelates and priests who read our blog that they can obtain a free traditional liturgical calendar! We have already reviewed this calendar and included part of that review with pictures below.

We are told that many priests, and several bishops, have requested free calendars over the last few years so this project has been successful.

For any priests or bishops who want a free calendar -- and for any layman who wants to send a calendar to a priest or bishop -- just click on the "CLICK HERE" below and fill out the form. Be sure to have the name and title of the cleric it should be sent to as well as the address.

Also, as most of us know having just gone through this for Christmas, the postal services is not only way behind but rates have gone way up. Due to this, for the first time, the Servants of the Holy Family are requesting that whomever requests the free calendar for a priest or bishop cover postage costs.

For the regular-sized calendar, those costs are $5.50 for within the US, and $25 outside the US. However, if it's being sent outside the US, they offer a mini calendar that can be sent for $5.50 outside the country as well.

When you go to the donate page, below, please enter the appropriate amount for postage and handling using your credit card and enter the type of calendar (full size or MINI) wanted.

Earthquake: Francis decrees women can occupy the former Minor Orders of Lector and Acolyte | Update: Full Text of Motu Proprio

|

| Swedish Lutheran female "bishops" |

[UPDATE: Full English text of the motu proprio at the end of the post.]

But after Vatican II, the new elites severed the minor orders (Acolyte, Exorcist, Lector, and Porter) and one of the Major Orders (the Subdiaconate) from the Diaconate and Presbyterate. They became mere functions that could be performed by laymen, though demanded (the functions of Acolyte and Lector) from those who aspired to the Diaconate.

The limitation of these venerable positions, that have always been held by men since Apostolic times (since they are intimately joined to the cursus honorum of the Priesthood), to men was broken today by a motu proprio of Francis opening them to "lay people"-- that is, including women.

The Motu Proprio is available here (in Italian and Spanish); Francis' letter explaining it is available here (in Italian). A summary of the motu proprio and the letter sent by Francis to the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith provided by Vatican News:

With a Motu proprio released on Monday, Pope Francis established that from now on the ministries of Lector and Acolyte are to be open to women, in a stable and institutionalized form through a specific mandate.

Fontgombault Sermon for the Epiphany (2021): As the Wise Men, Pay Attention to the Signs of the Times

Sermon of the Right Reverend Dom Jean Pateau

Abbot of Our Lady of Fontgombault

Fontgombault, January 6th, 2021

Vidimus stellam ejus.

We have seen His star.

(Mt 2:2)

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

My dearly beloved Sons,

Almost two weeks ago, the crib made us welcome to celebrate our Redeemer’s birth. Today, the Church invites us to attend His Epiphany, His manifestation to the world.

The birth of the Emmanuel, God with us, was indeed very private, hidden from the crowds: a secluded stable, Mary and Joseph alone, then a few shepherds summoned by the angels. That was all. The shepherds, silent men, probably kept the divine secret. Now, the time has come to proclaim this event. To whom will it be revealed, and how?

God is astonishing. On Christmas day, angels had borne the news of the divine birth to the shepherds. Isn’t that their role, as divine messengers? Today, to our utmost surprise, we can see arriving into our cribs a great show of colors, of animals, coming along with the mysterious Wise Men. Popular Christmas carols have many verses about them. These dignitaries’ arrival in Jerusalem must certainly have wrought havoc in the town. Very soon, the powerful were informed of the news, all the more as the Wise Men wished to meet them.

Epiphany and the Unordinariness of Liturgical Time

One chapter of Dom Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy is named “The Sanctification of Time”. This chapter shows how the Liturgical Calendar of the Church sanctifies time. The Liturgical Calendar does not provide merely an overlay of secular time. The Calendar is part of the recognition of the radically irruptive event of the Incarnation that changes time and space and reality forever. Of course this includes the celebrations of the feasts of the Saints, those specific celebrations of the making real of the grace of God in the lives of those who open themselves up in a total way to this grace, above all in the Blessed Virgin Mary. But the foundation of the Liturgical Calendar is the cycles that celebrate the Mysteries of the Birth, Life, Death, Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ. The Christmas cycle, which we are celebrating at this time, gives ultimate meaning to the secular, physical time when the days are becoming longer, a bit more light each day. In the Christmas cycle we celebrate the coming into the world of the Light that shines in the darkness. We celebrate the making flesh of God in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the birth of her child whose name is Jesus—he who comes to save. The climax of this cycle has always been the Epiphany, a feast older than Christmas, a feast that celebrates the fact that the event and the person of the Incarnation embraces not only time and space but embraces all the peoples of the world. And the feast of the Epiphany proclaims in its three-fold way the answer to the seminal question asked in the Gospels: who is this man Jesus? He is the one who is worshipped as God. He is the one who is the Son of God in whom his Father is well pleased. He is the one who changes water into wine, for he is the Lord of creation itself.

The Best Book on Its Subject: Dr. John Pepino Reviews Fiedrowicz’s The Traditional Mass

Reminder: Rorate Caeli Purgatorial Society

De Mattei: 2021 in the light of the Fatima Message and Right Reason [updated]

January 2, 2021

The

following is the text from a video lecture by Professor De Mattei from the

Lepanto Foundation with his best wishes to all Rorate Caeli readers for

the coming year 2021, in the Light of Our Lady of Fatima: “Light of Fatima, Light without shadows, Immaculate Light, Light of the

Dawn arising: we ask Thee to illuminate our steps in the darkness of the night.”

(The video in Italian can be found here: Il 2021 alla luce del messaggio di Fatima e della retta ragione - Prof. Roberto de Mattei - YouTube and Rorate will post the English video of this superb lecture presently).

The Message of Fatima

What really happened in 2020, the

dramatic year which has just come to an end? And what awaits us in 2021? What

are the prospects for our times?

The panorama we have before us is

hazy, difficult to survey, but I’ll try to do it from the stance of the highest

principles and greatest certainties, in the light of which, the history of the

world must be judged.

Among these great certainties there

is one more than any other that can help us find our way in the present and

future: the Message of Our Lady of Fatima in 1917.

We know well that Divine Revelation

ended with the death of the last Apostle and nothing can be added to it. The

Message of Fatima does not belong to the patrimony of revealed faith. It is

also true however, that, among private revelations, some concern the spiritual

perfection of individual souls, others have, on the other hand, a social reach

because they are meant for all mankind.

Well the message of Fatima is a

private revelation intended not only for the spiritual well-being of the three

little shepherds who received it, but for the entire human-race. And among all

the private revelations of the last century, none have had as much recognition

from the Church as Fatima has. In the space of a hundred years, seven Popes,

from Pius XII to Pope Francis have recognized and honored Our Lady of Fatima,

even if none have completely fulfilled Her requests.

In the year 2000, the Church officially

revealed the so-called Third Secret of Fatima, the last part of the message

revealed to the three little shepherds. An unfulfilled prophecy we must always bear

in mind[1].

The prospect described by the

Message of Fatima is tragic. The first tragedy that Our Lady presents to the

children is the terrible vision of Hell which the souls of unrepentant sinners

fall into.