PART II

THE COUNCIL AND THE ECLIPSE OF GOD

Beatissimae Vergini Mariae humillime dedicatum,

Quae cunctas haereses sola interemisti in universo mundo

A.

Historical

Introduction

The 20 Councils prior to the

Second Vatican Council had all been convened in order to extinguish the chief heresy or evil of the time: through

an ever deeper and clearer enunciation of Church doctrine. This Council was

different on two counts: first, in that it was not occasioned by any

contemporary heresy or evil, and second (as we have already noted above), in

that it was not dogmatic. It nowhere used the formula by which dogma is

infallibly defined, and moreover did not present itself as a dogmatic, but

rather as a ‘pastoral’ council, understanding pastorality as a matter of action

and reform. Pope Paul VI stated in a General Audience that: ‘differing from

other Councils, this one was not directly dogmatic, but doctrinal and pastoral’[1].

One might say that it was dogmatic indirectly

inasmuch as it contained dogmatic statements which had been declared in

previous Councils, but that it did not define, and did not intend to define,

any new dogma.

Sufficient doctrinal grounds

for convening a Council would in fact have existed in the expansion of

Modernism, ‘the sum total of all heresy’, or even sufficient pastoral grounds

in the growth of Communism and of the spirit of impurity of the 1960’s, and yet

the Council was not minded to combat these evils, but rather to implement a

program of reform both ad intra and ad extra: both within the Church and in

the relations of the Church to the outside world.

The fact that the Council

defined its own character in contradistinction to the previous, dogmatic

Councils is manifest in its avoidance of dogmatic definitions and its use of

discursive language [2],

as we shall presently see, but on a deeper level, in its skepticism towards the

Truth[3].

This fact also recalls Marx’s primacy of ‘praxis’ over Truth: ‘It is in praxis that

man must demonstrate truth, that is reality and power, the world-orientedness

of his thought’. As Professor de Mattei explains: ‘Praxis, that is the

historical outcome of political action, is for Marx the supreme criterion of

the truth of ideas, because action implicitly contains doctrine, even without

enunciating it’ [4]. Am Anfang war die Tat [5].

The two future Popes of the Second Vatican Council:

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini

The idea of a General (or ‘Ecumenical’) Council was presented by Pope John XXIII as ‘an impulse of Divine Providence’[6], ‘like a flash of heavenly light, shedding sweetness in eyes and hearts’ [7] at which the ashes of St. Peter and his other holy predecessors thrilled ‘in mystic exultation’; by Pope Paul VI it was similarly described as the effect of ‘divine inspiration’ [8], but the consequences that it was to have for the Church and the World tell another story.

The inception of Council

proceedings was marked by three victories for what Father Wiltgen calls ‘the

Rhine Group’ [9]. The

first was the postponement of the elections of candidates to the Council

commissions; the second was the placing of hand-picked men in these posts; and

the third was the rejection of all the work done preparatory to the Council.

The first victory was achieved after a meeting of the German Bishops in

the house of Cardinal Frings, where it was decided that the intervention to

frustrate the election process should be made by the non-German Cardinal

Liénart of Lille [10]. The

text was prepared by Monsignori Garrone and Ancel on the night before the first

session of the Council. On the following day, Cardinal Liénart duly asked

Cardinal Tisserant, who was acting as President, if he could intervene, and

when the latter informed him that it was against the rules, he took the

microphone and spoke nonetheless; his proposition was seconded by Cardinal

Frings in the name of other German Bishops, to the accompaniment of applause

from the floor, with the result that the election process was effectively

interrupted and the first session closed after less than 50 minutes. ‘That was

our first victory’, called a Dutch Bishop to a friend as he left St. Peter’s [11].

‘A happy and dramatic turn of events’ commented Cardinal Suenens in his diary,

‘and audacious violation of the rule! The destiny of the Council was largely

decided at that moment, and Pope John was happy with it.’

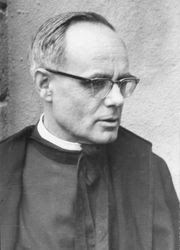

Cardinal Lienart

As to the second victory, the Rhine group drew up a list of candidates in the

Anima College, the German House of

Studies, under the presidency of the same Cardinal Frings, and began a process

of lobbying on the 19th October, the day following the first

session. Cardinal Heenan explained that many Fathers relied on this list, there

being insufficient time to investigate the suitability of the various

candidates for the Commission work, Monsignor Lefebvre noting that all the

candidates were of the same (liberal) tendency. In the end 79 of the 109

candidates presented by the Rhine group were elected, and the Pope added a

further 8 of these candidates to the Commissions. Meanwhile the Rhine group

expanded, eventually to include the Bishops of Germany, Austria, Switzerland,

Holland, Belgium, and France. ‘After this election’, writes Father Wiltgen, ‘it

was not too hard to foresee which group was well enough organized to take over

the leadership of the Second Vatican Council. The Rhine had begun to flow into

the Tiber… the alliance [12]

was able to operate effectively because it knew beforehand what it wanted and

what it did not want’ [13].

As to the third victory, it must first be explained that 2-3 years work prior

to the Council had been invested in preparatory schema containing some 2,000

pages and composed by 871 scholars. Their content was orthodox, as may already

be seen in the titles of the first four ‘dogmatic constitutions’: ‘Of the

Sources of Revelation’ [14];

‘Preserving Pure the Deposit of the Faith’; ‘Christian Moral Order’; ‘Chastity,

Matrimony, the Family, and Virginity’ - ‘titles alone... sufficient to

send any self-respecting liberal screaming to his psychiatrist’ [15].

Father Marie Dominique Chenu

Father Chenu had written to Father Rahner

before the Council to express his sense of ‘affliction and sorrow’ at the

‘strictly intellectualist’ tenor of the schemas which limited itself to

denouncing ‘inter-theological errors… without reference to the dramatic

questions which men ask themselves, be they Christians or not, by reason of a

change of the human condition, external or internal, which has never recorded

by history… the Council is becoming a sort of intellectual clean-up operation

within the walls of scholasticism.’

Father Karl Rahner

Father Rahner exposed to

Monsignor Volk, Bishop of Mainz, his strategy of substituting the schemas

already prepared with a new one. The Prelate invited a number of German and

French Bishops and theologians to the house ‘Mater Dei’ on the same 19th

October on which the lobbying began, to determine how to put this strategy into

action. The meeting was animated and lasted over three hours. Bishop Volk

convoked a further meeting on the same premises a month later. The capital

importance of the second meeting was the introduction into the new schemes of a

different style of language. Cardinal Siri described it as a discursive

criterion: ‘… there was an exclusion of the method of simple, concise

propositions for the affirmation of truths or for the precise condemnation of

errors.’ Professor de Mattei remarks: ‘the choice of a discursive method had as

its principal consequence the lack of clarity, the cause, in its turn, of that

ambiguity which was the dominant note of the conciliar texts’ [16].

Monsignor Volk, Bishop of Mainz

The outcome of the two

meetings was that the Dutch hierarchy issued a commentary in three languages,

the work of just one man, Father Schillebeeckx OP, which was presented to all

the Fathers as they arrived at the Council. It violently attacked the first

four schemas and proposed the fifth, the schema on the liturgy, for immediate

consideration. This schema, described by Father Schillebeeckx as ‘a true

masterpiece’ [17], was

the fruit of the only liberal-controlled Commission, that for Liturgical Reform

[18].

Two thirds of the Fathers, convinced by the Dominican’s stringent

argumentation, unsuspectingly accepted it. Such a majority would not in fact

have been sufficient to reject the preparatory schemes, but the European

Alliance succeeded in convincing the Pope to reject them notwithstanding [19].

Cardinal Ottaviani complained that the first scheme to be considered was not

doctrinal, as has been foreseen, but liturgical, but his remonstration went

unheeded [20].

Father Schillebeeckx

The First Session of the

Council, which was to comprise a mere six weeks of doctrinal discussion, closed

on December 8th 1962. Before the Second Session in September of the

following year under a new Pope, Bishops of various countries met for

discussions. While Bishops from other countries held their own meetings, the

Rhine group planned its strategy in Munich and in Fulda, on the initiative of

Cardinals Döpfner, Frings and König. Four Cardinals and 70 Archbishops and

Bishops took part, and were to arrive at the Second Session each with a

480-page plan in the hand. The theological expert who contributed most to the

work done at this meeting, on the documents on Revelation, The Blessed Virgin

Mary, and the Church, was Father Rahner, described by Cardinal Frings as ‘the

greatest theologian of this century’ [21].

Cardinal Konig

The press labeled the meeting

as ‘a conspiracy against the Roman Curia’ [22],

and in the course of the same summer, Cardinals Suenens, Döpfner, and Lercaro

elaborated a project for taking away the supervision of the Council from the

Curia and giving it to four Cardinal ‘Moderators’. Pope Paul agreed, and

appointed to these rôles the three Cardinals just mentioned ‘universally known

for their reformist ardor’ [23],

as well as the conservative, but ‘not very forceful’ [24],

Cardinal Agagianian.

Father Wiltgen sums up: ‘With

the Munich and Fulda conferences, the drastic changes that Pope Paul had made

in the Rules of Procedure, and the promotion of Cardinals Döpfner, Suenens, and

Lercaro to the position of Moderators, domination by the European Alliance (the

Rhine group) was assured.’[25]

When Pope Paul agreed to allow additional members to the commissions, the

European Alliance set about ‘drawing up an unbeatable list. This work was

greatly facilitated since … the European alliance had expanded into a world

alliance’ [26].

They met every Friday evening and were ‘able to determine the policy of the

controlling liberal majority’ [27].

Their power was to be re-inforced when they succeeded in having all their own

candidates elected as additional commission members. Consequently ‘there was no

need for any-one to doubt the direction in which the Council was headed’ [28].

Cardinal Suenens

It would exceed the limits of

a critical book of this nature to recount much more of the history of the

Council. Let this brief introduction, together with those to subsequent

sections, suffice to present the context, and to shed light on the motives, for

the doctrines that we shall be examining.

Cardinal Lecaro

This first sketch already

evokes some of the most important protagonists in the drama: on the one side

those that we may call ‘the children of light’, amongst whom we have seen

Cardinal Ottaviani, the very symbol of the Roman Curia and Prefect of the

Congregation of the Holy Office [29],

the Vatican organ responsible for the purity and the integrity of the Faith; on

the other side, ‘the children of the World’, a Freemason-studded cast: the

liberal (or ‘progressive’) theological experts and Bishops, principally of

French and German origin, well prepared and organized, and not shrinking from

unconstitutionality, or even from deceit, in their zeal to attain their ends;

in the center a Pope not endorsing the former group but acting as mediator and

conciliator between both. And so the scene is set for a drama that will bring

untold damage to the Hoy Church of God, the dynamics of which, like some vast

and infernal wheel, continue to thresh and to winnow humankind to this very

day.

C. The

Council’s Opposition to the Catholic Faith

We have said above that the

aim of this book is to show how the Council teaching opposes the Catholic

Faith. We use the neutral word ‘opposition’ not wishing to commit ourselves as

yet to describing the texts in question

as ‘errors’, ‘ambiguities’, or ‘attacks.’ We shall commit ourselves later after

having examined a sufficient number of such texts to make this assessment. We

shall proceed briefly to show:

- How the

Council opposes the Faith;

- How the

traditional World has responded;

- How the

present book responds;

- How the book

is structured in consequence.

- How the Council Opposes the Faith

The Council’s opposes the

Faith in two ways, verbally or tacitly: by what it says and by what it leaves

unsaid. The verbal opposition may be explicit or implicit. Explicit opposition

occurs when for instance the Council speaks of ‘churches’, which contradicts

Catholic teaching that there is only one church; implicit opposition occurs

when for instance the Council says that man is ‘the beginning … of every social

organization’[30]

insinuating that State authority derives from the people. In the latter type of

instance interpretations may vary, but should always take account of the

context. The Council’s opposition to the Faith is tacit when it passes over a

Catholic doctrine in silence, as when it fails explicitly to condemn

contraception.

- How the Traditional World has Responded

Relatively little criticism

has been levelled against the Council in postconciliar times. Reaction to

conciliar heterodoxy from the side of canonically regular Traditionalist

institutes has typically been of a Neo-Conservative bent. Canonically irregular

institutes, by contrast, such as that of the Society of St. Pius X and of the

Sedevacantists, as well as the traditionalist laity, have been more forthright

and outspoken [31], in

the footsteps of Monsignor Lefebvre and of renowned lay commentators of the

past, such as Professor de Oliveira and Jean Madiran. The only Prelate in good

standing with Rome who has opposed the Council as a whole, and that in vigorous

terms, is, to date, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò - ad multos annos!

- How the Present Book Responds

To show up the deficiencies of

the Council we shall respond by rebutting them with Traditional Catholic

teaching, since Tradition, together with the Holy Scriptures, constitutes one

of the two sources of the Faith. When such a doctrine is defined as dogma, we

shall often quote that dogma itself, since Faith consists in its dogmas.

Clearly this is not to play off one magisterial document against another, like

bringing up a white knight to a red knight on a chess-board; but rather to show

in the light of Tradition and dogma, in other words in the light of Church

doctrine, which has remained unaltered for 2,000 years and has progressed only

in the depth and clarity of its expression, that the latter text is false.

- How the Book is Structured in Consequence

Now since the heterodox texts are

spread out over all the Council documents, the material on which we must work

are the Council documents as a whole. How should a work of this type be

structured? The most effective way to evaluate the texts in question will

clearly be to examine them according to their themes: not chronologically,

then, document by document, but rather thematically. Our criterion for

establishing the themes of the Council texts will be what we understand to be

the underlying intent of the Council, namely the desire to adapt the Church to

the World. We shall, however, begin our study with another issue, which, as we

shall see in the course of the book, is in fact the most fundamental issue at

stake in the whole Council, and that is the question of Truth.

We begin, then, by speaking of

Truth; thereafter we consider the Council’s teachings concerning the Church in

Herself, then concerning the Church’s relations to realities outside Herself:

first to the non-Catholic Christians, then to the other Religions, to the

State, and finally to the World; we subsequently consider the Council’s

teaching on man, as being that which colors its view of the Church and indeed

its whole world-view: this study will focus on man in himself, in his

realization by his life choice, and in relation to God, so furnishing us with

the opportunity also to examine Council teaching on marriage, the priesthood,

the consecrated life, and the Holy Mass; we conclude the book with an analysis

of the whole Council from the theological and philosophical standpoints, and a

brief summary of its dynamics and import on the most profound level.

The book is consequently

structured according to the following scheme:

Introduction: Truth

Part

I: the Church

I) The Church in Herself;

II) The Church in relation to

the non-Catholic Christians;

III) The Church in relation to

the other Religions;

IV) The Church and the State;

V) The Church and the World;

Part

II: Man

VI) Man in himself;

VII) Man as realized in his

choice of life;

VIII) Man in relation to God.

Conclusion

IX) Analysis of the Council;

X) Summary of findings.

[1]6th August 1975, MD pjc, p.208

[2] ‘The major part of the

documents... consists... of vague generalizations, observations, exhortations,

and speculations on the likely outcome of a recommended course of action.’ MD

pjc, p.211

[3] see the section on Truth in

chapter I below

[4] RdM p.19-20

[5] Goethe, Faust, l.1237. Here Goethe,

with his customary brilliance and vigor, puts into the mouth of Faustus the

principle of the primacy of the will which he has reached after rejecting the

primacy of reason expressed in the prologue of St. John with the phrase: ‘In

the beginning was the Word.’

[6] Humanae Salutis, 1961, MD pjc, p.2

[7] Opening Speech to First

Session, MD pjc, p.2

[8] Opening Speech to Second

Session, MD pjc, p.2

[9] The Rhine Flows into the

Tiber, p.84, MD pjc, p.40. This is generally considered as one of the most

objective of all eye-witness accounts (as confirmed by the author’s first

spiritual director, a council peritus)

[10] Named in the ‘Pecorelli

list’of Freemasonic prelates

[11] Father Wiltgen p.17, op cit., MD pjc, pp. 29-30

[12] ‘the European Alliance’

[13] MD pjc, p.31, see Father

Wiltgen p.19 and p.63 recounts the story of the liberal take-over in pp. 17-19

of his book.

[14] De Fontibus – a title that expresses the

dogma that there are two sources of Revelation: the Sacred Scriptures (or

‘Written Tradition’) and Oral Tradition. We shall later see how the Council, in

a protestantizing move, was to place stress on the Scriptures at the cost of

(Oral) Tradition.

[15] MD pjc, p.38

[16] Cardinal Siri, ‘Il

post-concilium’ p.178, RdM III 7

[17] RdM p.238

[18] founded in 1948 and already responsible for the changes in all the

liturgical books, most notably for Holy Week. The Secretary from 1948-1960 had

been Monsignor Bugnini, reporting back to Cardinal Bea every week. There is little doubt that the

former was a Freemason, and the latter appears as such in the ‘Pecorelli List’

[19] MD pjc, pp. 39-40

[20] RdM p.239

[21] RdM p.304. On Revelation he maintained that Tradition is not constitutive of

Revelation but interpretative of it, and that the interpreter of the Scriptures

was not the Church but exegetes and theologians (RdM p.256); on the Blessed Virgin Mary that the

(classical and traditional) document concerning her would, if accepted, cause ‘unimaginable

evil from the ecumenical point of view...’ (RdM p.321) and that the title

‘Mediatrix of all Graces’ was unacceptable; on the Church he was to collaborate on a text promoting the innovative

ideas of Father Congar concerning a

‘pneumatic’ Church. This text was elaborated in secret in parallel to the

official one which represented the traditional doctrine of the Church as

‘Mystical Body of Christ.’ (RdM p.267 and p. 311) If this was the best

theologian of the century, one might well ask oneself who was the worst.

[22] RdM p.305

[23] Henri Fesquet, cf. MD pjc, p. 34

[24] Fr. Wiltgen, cf. MD pjc, p.

34

[25] MD pjc, p. 35

[26] Father Wiltgen cf. MD pjc, p.35

[27] Father Wiltgen, cf. MD pjc,

p.36

[28] ibid.

[29] La Suprema

[30] GS 22, see our discussion in

chapter VI on the dignity of man

[31] as is of course facilitated

by their ecclesiastical status