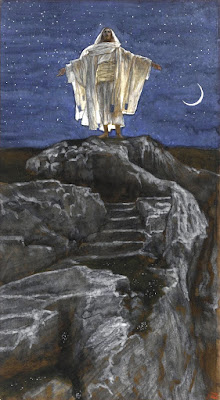

On Saturday, November 12, I delivered the plenary address at the Annual General Meeting of the Vancouver Traditional Mass Society/Una Voce Canada. The event was located at Holy Family Parish, an apostolate of the Fraternity of St. Peter. The text of my lecture is reproduced in full below, with notes at the end. All paintings are by James Tissot (1836-1902). Those who would like to listen to the audio (including Q&A) will find it here.

The Spirit of the Liturgy in the Words and Actions of Our Lady

Peter A. Kwasniewski

Reverend Fathers and friends in Christ: I thank all of you for coming this evening to hear my lecture, which I dedicate to Our Lady of Victories and to our saint of today, Pope St. Martin I. Rather than compromise one bit with error (as Pope Honorius had shamefully done about 15 years earlier), St. Martin energetically opposed the Monothelite heresy, on account of which he was abducted by command of the Byzantine emperor, exiled, imprisoned, and banished. Having died of exhaustion, he is revered as a martyr by both Roman Catholics and the Eastern Orthodox. He exemplifies how a pope is supposed to behave towards heresies, regardless of threats or punishments from the mighty of this world.

In the record of Sacred Scripture, the Blessed Virgin Mary is a woman of few words and few appearances. But the words she speaks and the role she plays are of such a depth that never, in a thousand centuries, would their wisdom and fecundity be exhausted, and for all eternity their echoes will sound and resound in the heavenly places. It can be said, without exaggeration, that Mary’s words and actions summarize the entire Christian life. They present the very pattern or archetype of that life; they are the whole of ascetical-mystical theology in nucleo. If we had nothing but Our Lady’s sayings and deeds, we would still know from them how to be perfect followers of Christ; we would have the pith or marrow of the Gospel.[1] It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that we can also find in them a guide to the spirituality of the liturgy—namely, to the correct internal dispositions and external actions of the formal, public, solemn prayer of the Church by which we most perfectly exercise our baptismal share in Christ’s priesthood and receive the fruits of His redemption, becoming those “worshipers of God in spirit and in truth” that the Father desires (cf. John 4:23–24).

Because of their very depth of meaning, Our Lady’s words and deeds are too vast a topic for one lecture. I will therefore limit myself to her words at the Annunciation; her silent, interior, but supremely active participation at the foot of the Cross; and her poignant words at the wedding feast of Cana.

1. THE ANNUNCIATION

When the archangel St. Gabriel announces to the Blessed Virgin that she is to bear a son, her reaction indicates, without any doubt, that she had already consecrated herself to perpetual virginity: “How shall this be done, because I know not man?” (Lk 1:34). Pregnancy is impossible, it seems to Mary, for she has no intention of knowing a man; otherwise, she would have assumed that the angel was speaking about a son to be born from her wedlock with St. Joseph. The angel replies: “The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the most High shall overshadow thee. And therefore also the Holy which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God” (Lk 1:35). In other words, this offspring will not be the result of a man’s action, the son of a man, but will be formed by a direct action of the Holy Spirit, a fruit of the Creator’s omnipotence, and therefore worthy to be called the offspring of God Himself.

In this exchange, there is a profound liturgical lesson for us. The Catholic Church is often spoken of as the Mystical Body of Christ, as the extension in space and time of the mystery of the Incarnation. Something similar can be said of the sacred liturgy: it is Christ among us, it is “the brightness of his glory and the figure of his substance” (Heb 1:3), as He is of the Father. Through it, the mysteries of the life, death, and resurrection of the Lord are made present and effective in our midst; the Lord Himself touches us, body and soul, to heal and elevate us. The liturgy, too, is the offspring of God in our midst, formed over long centuries by the brooding of the Holy Spirit upon the surface of human waters (cf. Gen 1:2). It is not a mere construct of human hands, a product of man’s initiative or labor or great ideas, but rather the unmerited gift of God, poured into our messy history as charity is poured into our sinful hearts (cf. Rom 5:5), and making something beautiful out of our nature, for our salvation. The liturgy is born from the womb of the Church, our Mother, by the power of the Most High overshadowing her. As we see in both Testaments, liturgy comes about primarily by God’s intervention, impregnating His bride with the seed of the Word. The liturgy is born from the Church’s virginal receptivity, and she retains her integrity and her honor in conceiving, giving birth, and mothering her child.

If this is true about the innermost essence of the liturgy, it follows that it is a fundamental error to think of the liturgy as if it were, first and foremost, the work of human hands, the offspring of our genius, our skills, our pastoral programs—as if we were the begetters of it, having the rights of a parent over it.[2] Rather, the liturgy comes from God, from the eternal liturgy of the heavenly Jerusalem[3]; it belongs to God alone, who entrusts it to our hands for safekeeping; it returns to God (and we return to Him through it), bearing our sheaves from the harvest, our increase of talents for His glory.[4] The Church as virgin bride says to God: “How shall my liturgy come forth, because I know not a man who can beget it?” And God answers her through Gabriel: “It is not for any man or any committee to form this liturgy; it is mine alone, in the hidden womb of the ages—the fruit of countless holy men and women moved by the Spirit of God, who first humbly receive, who, according to their capacity, adorn and enrich this patrimony, and who then faithfully transmit all the gifts they have received.”[5] In truth, Holy Mother Church never has the intention of “knowing a man,” that is, treating the liturgy as a “choice” made by partners in family planning, or worse, as a man-made product that can be modified at will, deconstructed and reconstructed as if it were a machine or a building or a toy.[6] She rather conserves and preserves the holy seed entrusted to her, utterly subordinating herself to it, treating it with the same reverence with which she would wash and anoint the Savior’s very body, as she lovingly and fearfully touches the flesh and blood of God.[7]

Returning now to the scene of the Annunciation, we see Our Lady giving her Fiat, on which the entire salvation of the world hinges. “Behold the handmaid of the Lord: be it done unto me according to Thy word” (Lk 1:38).

Note the double passivity of this statement. She does not say “I will do thus-and-such.” She says: “Be it done unto me.” Moreover, she does not say: “Be it done unto me according to my words” or “Be it done unto me as I understand it,” as if she were entering into a contract between equals in which both parties have worked out a mutual formula of agreement. No, she says “according to Thy word.” She does not grasp everything that this word contains or demands or portends. In fact, she knows that she is consenting to that which is absolutely beyond her understanding, and surrenders to it. One is reminded of the last words of Mother Catherine-Mectilde de Bar: “I adore and I submit.”

In the words of Dionysius the Areopagite, the perfect theologian “not only learns, but suffers divine things.”[8] The Blessed Virgin exemplifies this suffering of divine things. She lets them happen to her, she accepts, receives, embraces, and this is why she becomes pregnant with God. He is able to enter into her fully, substantially, because she gives herself, her humanity, her heart, soul, mind, and strength, to Him (cf. Mk 12:30). God does wonders in creation in proportion to the aptitude for wonders that He finds in the creature (cf. Mk 6:4–5). We may almost rephrase Mary’s response: “Make me suffer according to Thy Word”; “Refashion me, transform me according to Thy Word.”

This formula illuminates the immensely powerful spirituality of the traditional liturgy of the Church, whether Eastern or Western. The liturgy, as such, is given to us as a word of infinite density, as the “pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty” (Wis 7:25), as a Logos to be embodied in our midst, in our churches, on our altars, in our souls, in our actions. In imitation of the Theotokos, we are to become bearers of this word, which we receive. We do not make or create or fashion this word, but, like Mary, we receive it from another, we suffer it and are thus transformed by it, as potency is fulfilled by actuality.

Hence, for the liturgy to be Marian, for it to change us into her image, it must not—I repeat, must not—be subject to the will of the celebrant. It cannot be full of options, variations, adaptations, extempo¬ra¬ne¬ous utterances, improvisations. As Joseph Ratzinger has rightly said: “The greatness of the liturgy depends … on its unspontaneity.”[9] The novelty of having options to choose from in the missal, as if one were partaking of a devotional buffet, the novelty of allowing celebrants to build from modules and to improvise at various points of the Mass—a malleability that some liturgists identify (and praise) as the single most characteristic feature of the reformed Roman liturgy[10]—changes the fundamental character of worship in a radical way. Instead of expressing the Marian stance, “be it done unto me according to Thy word,” it expresses a distinctively modern stance of creativity, autonomy, and voluntarism: “I will do it according to my mind, my choice, and my words,” or, as Frank Sinatra colloquially crooned: “I’ll do it my way.” When Lucifer cried out “I will not serve,” he might just as well have said: I will not submit to a predetermined plan, I will not conform myself to a heavenly pattern (cf. Ex 25:9).

Lucifer’s anti-Marian stance, epitomized in his rebellious cry “I will not serve,” assumes many forms in the course of history. In the ecclesiastical sphere, it takes on the form of: “I will not preserve, I will not conserve.” Lucifer is the original liberal, inasmuch as he spurns order, discipline, rule, rubric, and tradition. He will not pass along something that came from another; everything has to be from himself, even if it is poor, banal, or ugly. What a stark contrast with Mary’s Ecce ancilla Domini! She knows that she is not the master, she is the ancilla, the slave girl. So much for modern Catholics who take the words of Jesus out of context: “I no longer call you servants … but friends” (Jn 15:15) and conclude that we are not servants in any way. His Mother, the holiest of all human persons and the most intimate friend of Christ, calls herself an ancilla, because she knows more and loves more than those who do not wish to belong completely to another.

The word “demon” comes from a Greek word meaning “one who divides.” Satan is a divider. One way he has lived up to this title is by dividing Catholics from our own heritage, our own tradition. This suits well his liberal agenda, which is to convince each generation that it is autonomous from past generations, and to convince each individual that he is autonomous from God, his fellow men, and his ancestors. The devil is permanently rootless, utterly without roots (that is why he goes “prowling about the world seeking the ruin of souls”), and he wants to uproot the rest of us. His greatest victory is not to hook us on pornography, alcohol, or drugs. Those things are wicked, to be sure, and have destroyed many lives and led to the damnation of many souls, but worse by far is cutting us off from the likelihood of conversion and contemplation by severing us from the Catholic tradition in which we will find all the medicine, the food and drink, the clothing, that we need for the healing of our sicknesses and the living of a godly life.

The liturgy, and therefore the Church herself, will not become healthy again—or, if she seems to be healthy in some places, will not be able to maintain that condition against the increasingly violent and demonic assaults of modernity—until the clergy have submitted to the Logos expressed in her perfectly evolved traditional liturgical rites with their stability of form, soundness of formulas, inexhaustible treasury of holy prayers, resounding orthodoxy, transcendent orientation, and otherworldly beauty. This, too, is what St. Paul says: “Follow the pattern of the sound words which you have heard from me in faith … guard the truth that has been entrusted to you by the Holy Spirit who dwells within us” (2 Tim 1:13-14). Formam habe sanorum verborum; bonum depositum custodi. When the liturgical rite demands the celebrant’s complete submission to its prayers, gestures, and ceremonies, it “swallows him up,” like Jonah’s fish, and hides him within its spacious confines, so that he disappears into the bright blaze of Christ: “And when they lifted up their eyes, they saw no one but Jesus only” (Mt 17:8; cf. Mk 9:8).[11] When the celebrant completely submits himself to such a rite, he enters into the kenosis, the self-emptying, of Christ; he most of all becomes alter Christus, mediating between mutable man and the immutable God. He practices the humility of St. John the Baptist, who said: “He must increase, I must decrease” (Jn 3:30). Hence the vital importance of recovering the traditional orientation of the priest, who, when the time of sacrifice arrives, should be facing East, together with the people he is leading to Christ.[12]

It is the very inflexibility of traditional liturgical forms that gives them their indomitable power to shape us, to change us, to be our fixed reference point, to be the rock on which the anchor of our restless hearts can catch hold. We who are so unstable, so wrapped up in our shifting emotions and poor thoughts, need an unshifting basis of prayer, rich and resonant with the accumulated piety and wisdom of the ages. Only in this way do we come to calmness, arriving at a harbor that mirrors our eternal haven. Only in this way can we put ourselves back together, so to speak, and achieve a wholeness that, left to our own devices, we could never hope to enjoy. The perennial liturgy is a source of sanity and stability for a Church storm-tossed, vexed with heresy, harassed by temptations of compromise with the world, the flesh, and the devil. It is a pearl of great price even in the most peaceful of times, but in an age of confusion and wickedness like ours, it is an urgently needed ark of safety, a fortress of truth, a tower of strength, a beacon of light. We may apply to it the words of the Epistle to the Hebrews: “Let us be grateful for receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, and thus let us offer to God acceptable worship, with reverence and awe” (Heb 12:28).

We can adapt and apply to the traditional liturgy the words with which the book of Wisdom describes its namesake:

She is a breath of the power of God, and a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty; therefore nothing defiled gains entrance into her. For she is a reflection of eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of his goodness. Though she is but one, she can do all things, and while remaining in herself, she renews all things; in every generation she passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God, and prophets. (Wis 7:25-27)

Liturgy rightly understood is the breath of God’s power, an emanation of His glory, giving us a foretaste of that glory and guiding us to the Promised Land. Nothing defiled, disordered, erroneous, heretical, or harmful can gain entrance into the liturgical rites of Catholic tradition, organically built up by the Holy Spirit and preserved from corruption, as was Mary’s virginity.[13] The liturgy reflects the One who called Himself the light of the world; it spotlessly mirrors Christ by presenting His mysteries not as empty commemorations but as efficacious signs that unite us immediately and directly to their substantial reality.[14] In this way the earthly liturgy, although limited in time and place, can do all things that Christ Himself did and does, renewing everything else by remaining itself (and by remaining true to itself).[15] Through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the Divine Office, the sacraments and sacramentals, eternal and incarnate Wisdom passes into holy souls of every generation and makes them friends of God, and prophets.

The foremost of these holy souls and friends of God is Our Lady. Just as St. John the Baptist was a prophet and more than a prophet (Mt 11:9, Lk 7:26), so, too, Our Lady is more than a participant in the liturgy: in her very person she is a living liturgy, the vessel through which Our Lord deigned to enter into space and time, to take on flesh and blood in our midst. She became the bridge between heaven and earth, God and man. She is not a priest but rather the very condition of the possibility of the priesthood—even, in a way, of her own Son’s priesthood. Her divine motherhood makes her greater than any ministerial priest, greater than any bishop or pope, and yet totally other than a priest, simply not in the same category as members of the Church’s hierarchy. She gives birth to the hierarchy, nurses it, educates it, leads it, wraps her protecting mantle around it. The whole of the Church is a child in the womb of Mary, in the arms of Mary. She is far greater than our structures. She is the very essence and meaning and purpose and goodness of our structures.[16] And women are privileged to bear in their very womanhood a natural likeness to Our Lady which, under the influence of grace, is capable of becoming a supernatural likeness.[17]

This is why clamoring for the involvement or activity of women in the sanctuary, whether as priests (which is impossible) or as deaconesses (which is equivocal and confusing, to say the least), or even merely as functionaries in a plethora of minor roles, is not simply a matter of mistaken priorities, but an assault on the metaphysics of God, the logic of the Incarnation, the ethics of our Marian response, and the poetics of the liturgical act. It, too, is a way of saying “Non serviam”: I will not serve the relationship of Father and Son, the descending agency of the Logos, the reception of tradition (that is, the Logos handed down through space and time), or the natural and supernatural symbolism of the rites.[18] I will not serve the supremacy of Mary and the woman’s virginal-maternal role in the order of creation; I will not serve the supremacy of Christ and the man’s vicarious role in the order of redemption; I will not serve the very distinction of sexes that makes possible the revelation of God’s preferential, passionate love and the irruption into our world of the miraculum miraculorum, the Incarnation of the Word.[19]

The eternal contradiction of Satan’s attitude is Our Lady’s Fiat: be it done unto me according to Thy word. This Fiat takes on a specific profile for each category of Christian.

(1) For the laity, our Fiat is to receive, to love, and to live the liturgical forms of our tradition, and not to think that it is a matter of indifference which logos we are receiving—one that comprises all ages, or one that derives from modernity.

(1a) For women, the Fiat consists in receiving and submitting to the order of the liturgy, which impresses upon us, ever more deeply, the virginal, bridal, and maternal character of the Christian life and of Our Lady in particular. All Christians receive and live this Marian identity, but women are privileged to do so existentially, in a bodily way that makes them living sacraments of Mary’s divine maternity—something no male human being can be.[20]

(1b) For men, on the other hand, this Fiat includes the possibility that we would be summoned by Our Lord to receive a share in His priestly power and to represent and exercise His priesthood at the altar of sacrifice. In responding to this call, we are not ceasing to be Marian but living out her attitude to the fullest; we are not becoming “agents of change” or “actors” in a modern sense, but rather “patients of change,” ones who will be changed into the image of Christ by ordination and by the discipline of the sacred liturgy.

(2) The Fiat of the clergy and anyone who serves as a liturgical theologian, educator, or minister of any kind is to suffer the liturgy to be itself and to form us, rather than acting upon it and forming it, as if we were still walking around in the apostolic age and had the charisms of the early Church in its embryonic phase, in its pre-Constantinian secrecy,[21] prior to the robust development of public, solemn, formal worship that culminated in the liturgical rites of the Byzantine empire and of the medieval Latin Church. Such perfected liturgical rites are the plenary manifestation of the Word, incarnatus de Spiritu Sancto, to which we are bound in filial piety by the very fact of our belonging to the perfect society of the Church, continuously one and visible until the end of time.

(3) The priest, more than anyone else, is called to be not an actor but a transmitter, a transparent communicator of wisdom that is not his own, a borrowed voice of Christ and the Church. As we said before, his entire attitude in ministry and especially at the altar should reflect those words of the Baptist, speaking of Our Lord: “He must increase and I must decrease” (Jn 3:30). Or, in the words of the book of Wisdom, the priest is a breath of God’s power, a reflection, a mirror, an image. He is not the reality itself, but participates in it; he must, therefore, at all costs avoid liturgical and extraliturgical activism, which expresses an attitude of self-absorbed promethean neopelagian domination that is utterly contrary to Marian spirituality. Activism here includes the many forms of liturgical manipulation, exploitation, and narcissism that have marred the face of the Bride of Christ and crippled her work during the past half-century, as well as forms of clericalism that interfere with the laity’s zealous fulfillment of their own social, political, and cultural responsibilities.[22]

(4) For male and female religious, the Fiat of our Lady is the very model of one’s entire way of life as a liturgical being who, by God’s grace, has chosen to live, as much as possible, for and from the Eucharistic Body of Christ, and, consequently, for those members of the Mystical Body of Christ who are in most need of one’s prayers, sacrifices, and works of mercy. Religious are called, above and before all else, to the corporate praise of God in a solemn and splendid way, such that the rest of the Church can catch fire from their zeal for the opus Dei. Christians who are lukewarm, distracted, even well-intentioned but superficial, are often brought to conversion by the potent witness of a community of monks, nuns, or friars offering up the sacrifice of praise, which makes manifest that God is the alpha and the omega, the first and abiding reality for us and for all human beings.[23] The religious could be described as a person who, having received through no merits of his own the grace of a penetrating awareness of his total dependence on God, has decided to live out this dependence as fully as he can, ordering everything else to this goal, and thereby carrying many others with him. Religious are the ones awake in a world of sleepwalkers. The Church depends especially on them to be generously devoted to the opus Dei, alert to the message of liturgical symbols, responsive to the gravitational pull of tradition. In this way, they serve to anchor and orient the rest of the People of God.

To everyone, Our Lady shows us that action proceeds from contemplation and returns to it; that any work we can do for God must be suspended like a bridge between the fixed points of liturgical prayer and personal prayer; that our hectic labor must be oriented to holy leisure, even as this earthly pilgrimage is for the sake of our eternal destiny. The Virgin Mary was not like St. Martha, busy about many things, and complaining that she never got any help. Rather, as St. Luke says, “Mary kept all these things, pondering them in her heart” (Lk 2:19; cf. 2:51). For her, what mattered most was the unchanging truth of God and its reflection on the face of Jesus. To this she gently but firmly directed everything else; she was ad orientem through and through. In our interior attitude towards liturgy, in our actual practice of worship, and in the ordering of our lives, we should imitate and internalize this theocentric and Christocentric orientation of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Where do we see this Marian orientation most of all? Stabat Mater dolorosa, iuxta crucem lacrimosa, dum pendebat Filius. “Standing beneath the Cross was the sorrowful Mother, weeping, while her Son was hanging there.” Fac ut árdeat cor meum in amándo Christum Deum, ut sibi compláceam. “Inflame my heart with love for Christ-God, that I may be pleasing to Him.”

2. THE FOOT OF THE CROSS

On Calvary, we see the inner reality and the archetype of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, namely, the bloody, life-giving Passion of the Son of God, by Whose stripes we are healed, by Whose Blood we are cleansed of our sins, by Whose Body, offered up, we are made into a sweet-smelling oblation.[24] St. John devotes two austere verses in his Gospel to the little flock, the congregation gathered at Golgotha:

Now there stood by the cross of Jesus, his mother, and his mother's sister, Mary of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalen. When Jesus therefore had seen his mother and the disciple standing whom he loved, he saith to his mother: “Woman, behold thy son.” After that, he saith to the disciple: “Behold thy mother.” And from that hour, the disciple took her to his own. (Jn 19:25-27)

Let us note several things about this scene. First, neither Mary’s name nor John’s is mentioned, but only “woman” and “the disciple whom he loved.” This stresses their anonymity: they are veiled in the presence of the aweful mystery; they are subsumed into it, they lose themselves in Christ. As St. Paul says: “you are dead; and your life is hid with Christ in God” (Col 3:3).

The account says they are standing at the foot of the Cross. Since we are not to read this passage as a “blueprint” for an actual liturgy, one cannot conclude that we ought to be standing throughout Mass (although our Byzantine brethren do stand during the liturgy, but for a different reason—because they are celebrating the resurrection, the anastasis or standing up again). Here at Golgotha, standing signifies attentiveness, a giving of oneself completely to the reality present. Mary and John are, to use a wonderful old expression, assisting at the Lord’s sacrifice. They do so not by speaking or singing or moving around, but by being present to Jesus in the depths of their soul. What we see, then, is the “Platonic form” of participatio actuosa or active participation: entering into the mystery in a way that is not primarily external or physical, but interior and metaphysical.[25] This is not to say, of course, that there should be no outward actions, words, and songs. It does show us, however, that the proper stance of those assisting at Mass is one of Marian receptivity and Johannine contemplation, and that the visible and audible signs used in the liturgy, as well as the bodily actions by which we respond to them, should be in service of this Marian-Johannine adoration of the Lamb and hospitality to the Bridegroom. When St. Luke tells us that “Mary kept all these things, pondering them in her heart,” he confides to us the very secret of Our Lady’s matchless participation in the mysteries of Christ. Indeed, she tells us herself: “My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Savior” (Lk 1:46–47), as if to underline that her praise of God is interior, hidden in the depths of her soul and spirit, and by a kind of overflow bursts forth into the great hymn of the Magnificat.

In a journal of private revelations recently published with ecclesiastical approval, Our Lord speaks the following words:

I offered myself to the Father from the altar of My Mother’s Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart. She accepted, consenting to bear the full weight of My sacrifice, to be the very place from which My holocaust of love blazed up. She, in turn, offered herself with Me to the Father from the altar of My Sacred Heart. There she immolated herself, becoming one victim with Me for the redemption of the world. Her offering was set ablaze in My holocaust by the descent of the Holy Spirit. Thus, from our two hearts become two altars, there rose the sweet fragrance of one single offering: My oblation upon the altar of her heart, and her oblation upon the altar of Mine. This, in effect, is what is meant when, using another language, you speak of My Mother as Co-Redemptrix. Our two hearts formed but a single holocaust of love in the Holy Spirit.[26]

This remarkable passage places emphasis on the unity of the sacrifice of Christ and His Mother. The account in St. John’s Gospel, while it testifies to that unity, also portrays the difference between the principal agent, Christ the Eternal High Priest, and the members of His body, Mary and John. They too are offering the unblemished Lamb, but not in the same way in which He is offering it in His very Person, in agony on the gibbet. John is a priest, to be sure, but this one time, on Good Friday, he is assisting “in choir.” Mary, too, as we have seen, is greater than any priest, but she does not dare to “compete” with the high-priestly act of her Son. In fact, she would never take upon herself the gift and mystery that Jesus bestowed on His Apostles when He made them priests, namely, the power of acting in persona Christi capitis, on behalf of Christ the Head of the Church.[27] As Theotokos she is greater than that priestly role, yet during her pilgrimage on earth she willingly subordinates herself to it, out of reverence for her Son, whose image is borne by the priest. In the beginning Mary received Jesus directly from the Father, but after the institution of the Most Holy Eucharist, Mary received Jesus from the hands of John, when he gave her holy communion until the time of her Assumption.[28]

The trio of Jesus, Mary, and John at the Cross is the Church’s liturgical life in its primordial form and perennial source, and we see in it the mysterium fidei, the mystery of sacrifice, charity, handing-over, and continuity, of motherhood and sonship, of unity and diversity, of anticipation, consummation, and perpetuation. Everything that is right about the traditional liturgical praxis of the Church—her “orthodoxy” in its original meaning[29]—may be found exemplified in this icon. Everything that is wrong with contemporary praxis, in its confusing tangle of artificial archaeologisms, novelties, deformations, banalities, and overall dullness or flatness, finds here at the foot of the Cross its bitter but health-giving medicine, the cure of a severe mercy that cuts off our foolish experiments. Our Lord is asking us today to imitate the prodigal son who, having wasted his great inheritance, his patrimony, woke up from his stupor and returned to his father, who re-established him in the family with a lavish sacramental feast.

We can highlight one last aspect of Calvary. There may have been a certain amount of back¬ground noise—the rough talk of Roman soldiers casting dice for garments, the occasional jeering of a scribe or a Pharisee—but the impression one gets from reading the Gospel accounts of the Passion is that of an eerie stillness, a pervasive silence that wrapped itself around the mountain like the dark cloud of Sinai. When Jesus speaks, it is a voice cutting through the silence, sounding the deep thoughts of crucified Love, like a cataract of water splitting the rock of hard hearts and saturating the tissue of soft hearts. One is reminded of the atmosphere of a private Low Mass or a Solemn High Mass in the traditional Roman rite: there is a sovereign stillness in the former, and a majestic authoritative utterance in the latter, that forces one to pay attention: O vos omnes, qui transitis per viam: attendite et videte (Lam 1:12), “O all ye that pass by the way, attend, and see…”

We can be certain that there was not a lot of didactic chatter going on at the foot of the Cross. “Mary of Cleophas, would you come and do the first reading? John over here will do the responsorial psalm, you don’t have to worry about that. Let’s gather around and announce our petitions; we could even ask these soldiers here to come and join us. And you, John and Mary, shake hands and say ‘Shalom!’” There is something tremendously disturbing about the Martha-like busyness, the lack of focus and “sonority,” and the almost Anaxagorean mixture of roles that characterize the reformed liturgy.[30] As Cardinal Sarah has recently reminded us (and many other imploring voices over the years could be added to his), a Roman rite liturgy without substantial silence that emerges from within its very structure and spirituality[31] is a liturgy that fails to confront us with the mystery of God, fails to integrate us in ourselves as sons of God, and fails to connect us with each other as members of His Mystical Body.[32] Pope Benedict XVI says: “Only in silence can the word of God find a home in us, as it did in Mary, woman of the word, and inseparably, woman of silence. Our liturgies must facilitate this attitude of authentic listening: Verbo crescente, verba deficiunt [when the word of God increases, the words of men fail].”[33]

I would add that when liturgy is bereft of the “sober inebriation” that arises from the use of Gregorian chant, and, in general, when liturgy is deprived of the splendor veritatis of beauty that befits it, we are far less likely to be stirred out of our complacent secularity or pacified in our noisy agitation. Lacking the resources of tradition to engage our senses, imagination, and intellect, we may attend the banquet but miss out consistently on the sweetest and headiest wine, which is tasted only in meditation and contemplation.[34]

3. THE WEDDING AT CANA

We all know the story of the wedding feast at Cana—the huge embarrassment about to occur if it becomes known that the wine has run out, the gentle intervention of Our Lady, the provision of copious amounts of the best wine by Our Lord’s first public miracle.

We stand to learn a number of things from Cana. Notice the marvelous attentiveness of Mary, her eye for detail, her mindfulness of what is happening around her. “They have no more wine” (Jn 2:3), she says to her Son quite simply, without panic or loquacity. She is completely present to the people, the celebration, the needs of the moment. In this she exemplifies for us that when we are celebrating the mystery of Our Lord’s marriage with the Church on the Cross, a mystery made present in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, we too must strive to be attentive, mindful, careful, totally present to what we are doing, so that we may give due honor to the Lord and receive from Him an ever-greater understanding of the ceremonies, the gestures and words, the ministers and the things they work with, so that our love of the Bridegroom might be intensified.[35] There is an old saying: age quod agis, that is, really do what you are doing—give it your whole mind and heart. When we approach the altar, when we assist at Mass, we should bring to it this Marian disposition of total “availability.”[36] For ministers in the sanctuary, this obviously means knowing your role as well as you can and focusing on what you are doing as you are doing it, in an intelligent and prayerful spirit. For laity in the pews, it means preparing well for Mass, learning more about the liturgy and making an effort to pray it, so that you can assimilate more fully the spiritual riches it contains.

But there is a further lesson at Cana, too, one that is still more pertinent to our times. Our Lady notices the problem of the moment: “They have no more wine.” She has, one might say, correctly interpreted the signs of the times. The families who planned the wedding, no doubt people of good will with the best of intentions, messed up in their calculations. Their attempt at celebration is rushing towards failure, and only the Lord can save it from disaster. So, too, at the time of the Second Vatican Council, the bishops planned a wedding of Catholicism with modernity, and the liturgical reform devised a new type of “celebration” so as to involve the guests more actively in the drinking and dancing. We may assume plenty of good will, but all the good intentions in the world do not, of themselves, guarantee good wine—the good wine of orthodoxy, which means right worship as well as right doctrine. The conciliar wedding feast, which had been billed as a new Pentecost, quickly ran out of wine in the postconciliar period, to the humiliation and consternation of all, including Pope Paul VI who lamented on June 29, 1972 that “from some fissure the smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God.”[37] Vast numbers of guests have long since fled the feast. What, then, is to be done? First, we must admit that Our Lady’s diagnosis is exactly correct for us, too: “They have no more wine.” Our calculations, our modernizations, have failed and we desperately need help from a different source than the aggiornamento on which we had relied. Second, she says to us, as she said to the servants at Cana: “Whatsoever he shall say to you, do ye” (Jn 2:5). As with her great Fiat, we find in these words a lucid reflection of the spotless mirror that is Mary’s soul, she who always does what He says, who always submits to whatever He demands, even when it costs her everything. She knows that her Son can supply the way forward, can provide the new wine that is urgently needed.

And what will the Lord say to His Church today? He will say what He has said to her in every age, with merciful clarity and consistency: He will speak nothing other than the very Word of God, which is contained in Scripture and Tradition, without any attenuation, diminution, distortion, or extraneous elaboration. This is the wine that is new not because it was made just a few minutes ago but because it flows from the new Adam, the new Song[38]; it is perennially fresh, eternally true, delighting the taste of the inward man; it never goes sour, and one never tires of drinking it. Whatsoever he says in Scripture and Tradition, this we must do, must believe, internalize, and act upon, without fear of what others will say or think. If the Lord says that marrying someone who is already married is adultery, which can never be allowed, we will accept it without contradiction. If the Lord says that riches are a danger to the soul and that we are not to seek after them, we will embrace His poverty and not promote unbridled capitalism. If the Lord says that all power in heaven and on earth has been given to Him and that we are to make disciples of all nations, we will accept His Kingship over individuals, families, societies, and states, and not dabble with the poison of liberalism and its axiom of the necessary separation of Church and State, which St. Pius X condemned as “a thesis absolutely false, a most pernicious error.”[39] Most importantly, because it touches most intimately on His very flesh and blood, soul and divinity, we will accept, embrace, and revere His holy mysteries as they have been handed down to us in the liturgical rites of Holy Mother Church—rites organically developed over the centuries under the unfailing guidance of His Holy Spirit.[40] “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever,” as it says in the Epistle to the Hebrews (13:8), and He speaks to us the same Word yesterday and today and for ever: the infallible and inerrant word of Scripture, and the unshakeable foundation of apostolic Tradition, expressed through and supported by ecclesiastical traditions that the Church had always venerated until her leaders, caught up in the antinomian spirit of the 1960s, succumbed to the allurements of Modernity.[41]

Let us dwell for a moment on this last point, namely, the historically famous veneration of the Church of Rome for its own heritage, the jealousy of Rome for its rites and doctrines, to which we may compare the attitude of Eastern Christians towards the Byzantine Divine Liturgy and the testimony of the Church Fathers. It seems to me that this is simply the ecclesial translation of the innermost spirituality of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who “kept all these things, and pondered them in her heart.” Note well how much is packed into that first phrase. (1) She kept all these things, held on to them for dear life, and did not dare to discard them. (2) She kept all these things: she did not sort through them and chuck out what didn’t suit her, or bothered her, or challenged her, or baffled her, but preserved them all in her heart, in her prayer, in her life.[42] (3) She kept all these things. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, one does not engage in a generic keeping, a receiving of just anything, it matters not what. Rather, one keeps “these things,” the deeds of God on behalf of Israel, and the mysteries of Christ on behalf of mankind. It is a specific preservation of what has been concretely given. It is like one’s proper name, the name that expresses the irreducible singularity and mystery of the individual person. The Mother of God is named by her parents “Mary,” not “the Eternal Feminine” or the “Earth Goddess.” Her son is named “Jesus,” not “Redeemer” or “Moral Teacher” or “Hero” or “Ideal.”[43]

Instead of looking to Mary our Mother and imitating her tenacious “keeping,” we have looked too much to modernity, the spirit of which is not merely in tension with but contrary to Mary’s virtues and her contemplation as the Seat of Wisdom.[44] What she keeps and ponders is ultimately her Son, eternal and incarnate Wisdom, in all the richness of his individuality, the scandal of his particularity. For this reason, Buddhists or Moslems cannot receive and keep as Mary did, and as we ought to do. They ponder things, to be sure, but these things are either errors or half-truths. They are not the deeds of the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and the mysteries of God Incarnate, Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ of Israel.

What is true for the Blessed Virgin Mary is true for all Catholics: we have a concrete historical tradition, not a jumble of generalities, platitudes, or ideals. Our traditional Catholic practices emphasize this fact. Kneeling, while intelligible as a sign in itself, also relates to the humble adoration of the Magi and St. Mary of Bethany anointing the feet of Jesus. Ad orientem worship, while intelligible as a cosmic symbol, points to the transcendent God who has revealed Himself to Israel as a thrice-holy consuming fire and as the Orient who breaks in upon the world and will return from the East.

The same combination of universal intelligibility and the “scandal of the particular” is found in the great historic liturgies of East and West. Coming to birth in a particular place, time, and culture, they are highly definite, individualized, unmistakably what they are and nothing else, and over the centuries, they develop a characteristic depth, a sort of “personality,” owing to the various influences that act upon them. At the same time, they show a remarkable capacity to be transplanted by missionaries to new places, times, and cultures, where they captivate and shape new peoples for Christ. The very density of their substance contains and conveys the religious signs to which man was created to respond, by the grace of God acting on his natural faculties. In their variety, the traditional Eastern and Western liturgical rites give polyphonic utterance to the unity, holiness, catholicity, and apostolicity of the Church of Christ. Each has its peculiar strengths; no one of them can be mistaken for any other. Once they have solidified, as it were, into their final forms, one does not attempt to mix them: one does not mix up the Byzantine and the Roman, or the Roman, the Ambrosian, and the Mozarabic. Each has to be respected for the specific, concrete tradition it embodies. Those who belong to a certain rite enjoy the privilege and the duty of receiving it, caring for it, preserving it, and passing it on to their descendents.[45]

As Roman Catholics, we inherit the Roman rite. This rite is the most ancient of all, going back to a period so early that there was not yet any dispute among Christians about the divinity of the Holy Spirit, which explains the lack of an epiclesis in the Roman Canon. It was simply not needed; the entire theology of consecration is different. For the early Christians in Rome, it was enough to ask the Father to do something (in this case, convert the bread and wine into the Body and Blood) because He is pleased with the Son. If the Father grants His paternal blessing, the effect follows irresistibly. It was only later, in response to the Eastern heresy of Macedonianism, that Byzantine Christians thought it desirable to invoke the divine Spirit to bring about the conversion of the gifts. The mid-twentieth century fad of introducing epicletic prayers into Western liturgies—and even worse, of creating new anaphoras where they had never existed before—reflects not only recklessly irresponsible scholarship but a profound betrayal of the apostolic tradition of these liturgies. We are dealing, once again, with an anti-Marian stance: rather than keeping all these particular things that the Lord has entrusted to us, we pick and choose, mix and match, invent and discard.

If, therefore, we wish to be like Mary, Catholics of the Roman rite should receive, keep, and ponder the Roman rite as it has developed organically over time, since it is the embodiment for us of the deeds of God and the mysteries of Christ. It is our liturgical “scandal of the particular.” Just as Jesus was not everyman or no man but this male Israelite, born of the house of David in Bethlehem, reared in the village of Nazareth, a mendicant preacher who was put to death as a malefactor by Roman authorities, so too, the Roman rite is not an open-ended, infinitely malleable structure for liturgical experimentation, but a rite of truly noble simplicity that originated in a tiny area of Italy and grew, slowly but surely, into a magnificent tree bedecked with Gallican ornaments.[46] It is, in other words, perfectly and absolutely itself and nothing else. Its unique Canon, its ancient lectionary, its cycle of propers and orations, its calendar, all these things make it to be itself and nothing else.

Consequently, the rejection, manipulation, or transmogrification of this rite by Roman Catholics is nothing less than an act of violence against their own identity, a kind of institutional suicide. Since the evolution of liturgical rites is always under the guidance of the Holy Spirit[47] and it cannot be maintained by any faithful Catholic that the Holy Spirit was absent from the Church for the 400 years between the promulgation of the Missal of Pius V and the promulgation of the Missal of Paul VI (much less that He was absent from the development of the liturgy from St. Gregory the Great down to the Council of Trent), it follows that the liturgical reform as it took place under Annibale Bugnini, tainted by a combination of antiquarian and modernist principles, rejected the scandal of the particular, disowned the concrete historic tradition of Catholicism, forsook the theology of the Council of Trent,[48] and in all of these ways, offended the Person of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who entrusts Himself to us through the authentic rites and traditions of the universal Church. The meltdown, the hardships, the crises through which the Catholic Church has passed since the Second Vatican Council are divine chastisement for this act of unprecedented hubris against organic continuity with the apostolic rite of Rome. “He hath scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart” (Lk 1:51): this, I believe, would be Our Lady’s commentary.[49]

I spoke earlier of a “marriage between the Church and modernity.” Fortunately, every metaphor has its limitations. The Church is not actually wedded to modernity; the Church is wedded to Jesus Christ. But in recent decades it would seem that all too many Church leaders have attempted a second marriage, wishing to exchange the sweet yoke of Christ for the harsh burden of intellectual fashion, the ever-elusive “relevance” that leads to supreme irrelevance. For fifty years we have seen an embarrassing infatuation with modernity, an ill-starred romance, and as with all extramarital liaisons, this one, too, must come to an end. In this season of grace, the Lord Jesus is calling His Church on earth to return once more, with humility and repentance, to her first love. He waits patiently for her conversion from the vain pursuit of worldly idols to the stability of sacred Tradition.

In conclusion, I would like to make a brief remark about the current situation of the Church. It is hardly coincidental that the tremendous moral and doctrinal crisis through which the Church is now passing, where some of her shepherds are calling into question fundamental truths about marriage and the family, is occurring in a body of believers who have been habituated by fifty years of liturgical change into thinking that the most sacred mysteries, the most awesome realities of our Faith, are subject to our control, our desires, our “better ideas,” our duty to modernize everything in a vertiginous aggiornamento. Such attitudes and the reforms that enshrined them have contributed to a loss of basic reverence towards mysteries received, such as human life, the love of man and woman, the once-for-all redeeming death of Christ on the Cross, the sacraments of the Church, and time-honored liturgical rites. If we cannot revere our own tradition, which is the result of so many centuries of prayer, devotion, piety, and intelligence operating under the influence of the Holy Spirit, why should we revere anything that is said to be a “given”? Natural law stands or falls with divine law, and our apprehension of nature itself stands or falls with our acceptance of the true Christian religion.[50] If we desire the restoration of good morals, we must first restore the virtue of religion, the foremost of moral virtues, by which we offer God fitting worship along the path of tradition. By doing this, we signify our intention to surrender ourselves to Him as our first beginning and last end; we abandon the Enlightenment folly of taking ourselves as the point of origin and arrival.[51] Within the safety of the Church’s tradition, in the intimate encounter with the glorified Christ who suffered for our sins, we will find again the illumination and the strength to live righteously.

Our Blessed Lady shows us the best way, the true way, the holy way. It begins with “Be it done unto me according to Thy word,” culminates in her adoring and co-redemptive silence at the foot of the Cross, lingers lovingly in her life of Eucharistic communion, and finds completion in her glorious Assumption, where she—the very personification of the heavenly Jerusalem and its ineffable liturgy—is taken up by the hand of her Son and led into His eternal wedding feast. Let us follow her with all our hearts, as we walk confidently in the Marian spirit and power of the traditional Latin liturgy.

Thank you for your kind attention.

NOTES

[1] St. Thomas notes at one point that “the action of Christ was our instruction,” actio Christi fuit instructio nostra (Summa theologiae III, q. 40, a. 1, ad 3. The same may be said of our Blessed Mother, because her actions, too, were sinless and perfect.

[2] It could be objected that Mary and Joseph did have the rights of a parent over Jesus, as indicated by Lk 2:51: “He was obedient to them.” But this was a choice made by Our Lord, since naturally He was superior to them both in His divinity and in His humanity—something hinted at by His reaction to His Mother’s words: “Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us? Behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing” (Lk 2:48), to which He responds: “How is it that you sought me? Did you not know that I must be in my Father's house?” (v. 49), as if to say: The one to whom I am truly subject from all eternity is My Father; but I consent to be subject to you in the economy of salvation. Jesus says something similar to St. John the Baptist when the latter is surprised that Jesus would be baptized by him (Mt 3:13–15).

[3] This is a point frequently made by Joseph Ratzinger in The Spirit of the Liturgy and elsewhere, but it can be extrapolated also from the Book of Revelation, many liturgical texts, Pius XII’s Encyclical Letter Mediator Dei, and Vatican II’s Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium.

[4] Ps 125:7; Lk 19:11–27.

[5] One may ask whether this view ignores the obvious fact that it was human beings who built up the liturgy with prayers, ceremonies, processions, feastdays, etc. No, not at all. But what Christians contributed, they always contributed to a given structure that preceded them—as if they were adding ornaments to a Christmas tree. A better comparison would be the building of a church. The fundamental plan of a Christian church is a given, not something we design ex nihilo. However, the architects have to decide how this plan will be realized in this place and in these circumstances. Their final work will be more or less adequate to the nature and purpose of a temple. Moreover, many people will contribute wealth to the building of the church, and, over time, more people will add ex voto offerings. The church is therefore built by many and ornamented by many, but its basic plan preexists any of their efforts, and its success, in the end, depends on how well it corresponds to the “ideal temple” that is in the mind of God and descends from above, like a bride adorned for her husband (Rev 21:2). One might say that this is a highly neoplatonic conception of church architecture, to which my response would be: yes—what other conception is worth considering? It is certain that the Church Fathers thought in precisely this way.

[6] Wherever this aberrant approach prevails, therefore, we can see that it is not the Church acting, much less Christ, but churchmen who are abusing their authority and, to the extent God permits it, obscuring and obstructing the activity of the Church of Christ and stifling her maternal memory (cf. Lk 2:19).

[7] The objection of traditional Catholics to laypeople receiving the consecrated Host in their hands or distributing it to others has nothing to do with whether or not we deserve to have the Body of Christ touch our bodies. Obviously, whoever receives the Holy Eucharist is physically touched by the Real Presence of Our Lord, and no one is worthy, absolutely speaking, of this divine gift except God Himself. The problem has to do with the understanding of ministry. The priest is a man set apart by God and metaphysically changed by the indelible character of Christ’s priesthood, all with a view to consecrating, handling, distributing, and caring for the sacramental Body of Christ and those things that directly pertain to it (such as absolving sins that prevent us from eating the bread of life, apart from which we will die in our sins). The hands of the priest are specially anointed so that they may be worthy of performing these awesome tasks. The layman, in contrast, is empowered by his baptism to receive the Body of Christ, but not to have, as it were, a ministerial power over It at the altar and the communion rail. To act otherwise is to arrogate to oneself an activity that is proper to Christ the High Priest, by His gift and choice, and therefore to insult Him by visibly undermining His determinations as well as the dignity of His ordained ministers.

[8] Summa theologiae II-II, qu. 45, art. 2: “Hierotheus est perfectus in divinis, non solum discens, sed et patiens divina.” In his commentary on the De Divinis Nominibus, St. Thomas remarks: “he does not merely gather up knowledge of divine things in his intellect, but by loving them is united to them in his heart” (“idest non solum divinorum scientiam in intellectu accipiens, sed etiam diligendo, eis unitus est per affectum”): ch. 2, lec. 4, n. 191, Marietti 59. Cf. ST 1, q. 1, a. 6, ad 3.

[9] The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 166.

[10] This appears to be Msgr. Kevin Irwin’s position.

[11] The comparison to Jonah’s fish is admittedly whimsical, but not beside the point. We know from Our Lord that Jonah is a type of Himself gone into the tomb and resurrected, meeting His disciples on the shores of Galilee (cf. Mt 12:39–41; Jn 21:1). Before Jonah is swallowed up, he is running away from his mission. Once he is overcome by a greater power, he learns to submit and to obey, and becomes a prophet whose word effects conversion. There is an exact parallel in the realm of the new evangelization. As long as churchmen think they will do their work with their own lights and liturgies, their efforts are doomed to failure. Once a priest submits to the great power of the sacred liturgy, he will “learn obedience by the things which he suffered” (Heb 5:8), and will be projected onto the beach of modernity with the humility and zeal of one who has something worthwhile to share, something burning in his heart (cf. Lk 24:32), to convert the poor Ninevites who don’t know their left hand from their right hand, or, to give a more up-to-date example, a woman from a man.

[12] For further thoughts on the necessity of ad orientem worship, see my lecture “The Sacrifice of Praise and the Ecstatic Orientation of Man.” Cardinal Sarah has spoken beautifully of the connection between silence and ad orientem: “Liturgical silence is a radical and essential disposition; it is a conversion of heart. Now, to be converted, etymologically, is to turn back, to turn toward God. There is no true silence in the liturgy if we are not—with all our heart—turned toward the Lord. We must be converted, turn back to the Lord, in order to look at Him, contemplate His face, and fall at His feet to adore Him. We have an example: Mary Magdalene was able to recognize Jesus on Easter morning because she turned back toward Him: ‘They have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.’ Haec cum dixisset, conversa est retrorsum et videt Jesus stantem. – Saying this, she turned around and saw Jesus standing there’ (Jn 20:13-14). How can we enter into this interior disposition except by turning physically, all together, priest and faithful, toward the Lord who comes, toward the East symbolized by the apse where the cross is enthroned? The outward orientation leads us to the interior orientation that it symbolizes. Since apostolic times, Christians have been familiar with this way of praying. It is not a matter of celebrating with one’s back to the people or facing them, but toward the East, ad Dominum, toward the Lord. This way of doing things promotes silence” (source).

[13] The finest exposition of the all-important concept of “organic development” is Alcuin Reid’s The Organic Development of the Liturgy: The Principles of Liturgical Reform and Their Relation to the Twentieth-Century Liturgical Movement Prior to the Second Vatican Council (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005).

[14] In Mediator Dei, at nn. 164 and following, Pius XII explains how the mysteries of the life of Christ are recounted, reawakened, reapplied throughout the Church’s year, and how the liturgy itself beseeches the Lord for a share in the graces obtained and represented by those mysteries.

[15] The liturgy is an Archimedean point: by its fixity, it can move the universe.

[16] In the sense that whatever is good, holy, beautiful about these structures is precontained in and exemplified by the Virgin Mary, in the perfections of her body and especially her soul. The Church is, to so speak, a reflection or externalization of the plenitude of Mary’s divine virginal motherhood.

[17] See my article “Incarnate Realism and the Catholic Priesthood.”

[18] See “Should Women Be Lectors at Mass” and “Are We God’s ‘Sons and Daughters’?”

[19] See H. J. A. Sire, Phoenix from the Ashes: The Making, Unmaking, and Restoration of Catholic Tradition (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2015), 317.

[20] See the article referred to in n. 17.

[21] Cardinal Journet speaks of privileges uniquely apostolic in his Church of the Word Incarnate and its summary Theology of the Church, noting that the apostles received and exercised certain powers that no other Christians, including their successor bishops, ever enjoyed or could enjoy.

[21] Cardinal Journet speaks of privileges uniquely apostolic in his Church of the Word Incarnate and its summary Theology of the Church, noting that the apostles received and exercised certain powers that no other Christians, including their successor bishops, ever enjoyed or could enjoy.

[22] It has often been pointed out (including by Pope John Paul II) that the true vocation of the laity, namely to infuse the Spirit of Christ into the mores and laws of the people among whom one dwells, has been eclipsed by the “shortcut” of the clericalization of the laity, whereby their busy-work in the liturgy is taken for a sign of involvement when, in reality, it points to a failure to undertake their God-given tasks outside of the sanctuary and to let the clergy be the clergy.

[23] See the Silverstream lecture mentioned in note 12.

[24] Is 53:5; Heb 9:22–26, 10:19–22; 1 Pet 1:18–19; Eph 5:2.

[25] In other words, the exemplar of the Mass (and of our liturgy in general) is not the Last Supper but the Sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. This is precisely what distinguishes a Catholic understanding of liturgy from a Protestant one. The oft-cited verse “where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in the midst of them” (Mt 18:20) is, in fact, most perfectly fulfilled on Calvary: as we see in artistic depictions, Mary is on one side, John on the other, and Jesus in the middle, in their midst, really, truly, substantially present in the offering of His precious Body and Blood to the Most Holy Trinity for our salvation.

[26] A Benedictine Monk, In Sinu Jesu. When Heart Speaks to Heart: The Journal of a Priest at Prayer (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2016), 168.

[27] The hierarchical relationship of the priesthood and the laity is comparable to that of husband and wife, which Pius XI compares to the relationship of the head and the heart in the body: see Encyclical Letter Casti Connubii (December 31, 1930), §27.

[28] There is a parallel to this under the Cross, when she received the lifeless but still divine Body of her Son from St. Joseph of Arimathea.

[29] See Ratzinger, Spirit of the Liturgy, 159–60: “We must remember that originally the word ‘orthodoxy’ did not mean, as we generally think today, right doctrine. In Greek, the word doxa means, on the one hand, opinion or splendor. But then in Christian usage it means something on the order of ‘true splendor,’ that is, the glory of God. Orthodoxy means, therefore, the right way to glorify God, the right form of adoration.” Geoffrey Hull develops this point at length in The Banished Heart.

[30] According to Anaxagoras, one of the Presocratic philosophers, nothing is wholly and purely what it is, but everything has a little or a lot of everything else mixed in with it. This was how he attempted to account for how you could get one substance from another: if everything’s already in everything, you can get anything from anything else. The liturgical parallel is not hard to see: it is rare to find a modern liturgy in which anyone is wholly and purely what he or she is supposed to be, allowing each role its own integrity. This, of course, is contrary to Sacrosanctum Concilium §28, but no one pays attention to that document—least of all those who invoke it as a blanket justification for their liturgical opinions and practices.

[31] I make this qualification because in the reformed liturgy, silence, when it exists, is usually an awkward pause or caesura introduced at the fault lines of the modules out of which the sequential liturgy is composed. In other words, a priest after the homily will just sit there for a while, expecting the congregation to soak in his words of wisdom. This is an entirely artificial type of liturgical silence. Real liturgical silence arises when a priest or other minister is performing his ministerial actions silently or sotto voce, so that the people can, as it were, hold on to the hem of his garment and join in the action. One might call this “pregnant silence” because it is part of the ritual and filled with its own meaning. The bad kind is somewhat like a stillbirth or a wind egg. Think of it this way: a Buddhist could sit still for a long time, but this would not be Christian silence; and similarly, a priest could sit still for a long time, but this would not be liturgical silence.

[32] Of course the Byzantine tradition does not privilege silence in the same way as the Western tradition has done, but this is precisely one of those deep differences between rites that we need to understand, respect, and preserve. The continual singing of the Divine Liturgy is one form of worthy doxologizing, and the Roman custom of stretches of silence alternating with chant and polyphony is another form of worthy doxologizing. To think that there is or should be only one approach to public worship is tantamount to maintaining that there should be only one liturgical rite for all Christians and only one way of celebrating it, an opinion that is superficial in the extreme, not to say impious.

[33] Benedict XVI, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Verbum Domini (September 30, 2010), §66.

[34] To these resources of tradition one may apply the joyful words of the Psalmist: “They shall be inebriated with the plenty of Thy house; and Thou shalt make them drink of the torrent of Thy pleasure” (Ps 35:9).

[35] There are many fine resources we can use. Among the best is the new book by Fr. James W. Jackson, FSSP, Nothing Superfluous: An Explanation of the Symbolism of the Rite of St. Gregory the Great (Lincoln, NE: Fraternity Publications, 2016).

[36] The philosopher Gabriel Marcel speaks of disponibilité, the ready willingness to “dispose of oneself” in service of another.

[37] A transcript of his words has never been published, but a summary with selective quotations may be found at the Vatican website, including this phrase, which is attributed to Paul VI as a direct statement: “da qualche fessura sia entrato il fumo di Satana nel tempio di Dio.”

[38] St. Clement of Alexandria calls Jesus Christ “the new song.” See Source Readings in Music History, ed. Oliver Strunk (New York: Norton, 1950), 63.

[39] Pius X, Encyclical Letter Vehementer Nos, February 11, 1906, to the bishops and people of France.

[40] The Lord promised that the Holy Spirit would lead His Church into the fullness of truth. Since the truth of Christ is most of all proclaimed and efficaciously communicated to us in the sacramental rites, there is no area of the Church’s life more protected and more guaranteed to be full of truth than her liturgical and sacramental life, as long as one is looking at that life as it actually unfolded under the reign of the Holy Spirit, rather than as it was artificially dissected and refashioned by scholars operating by false principles of modern thought and under the false assumptions of the Corruption Theory and the Pastoral Theory. To their work, it is not clear that one may ever attribute the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

[41] For an excellent discussion of the different types of tradition and why they are all important (even if some are more changeable than others), see Fr. Chad Ripperger, Topics on Tradition (n.p.: Sensus Traditionis Press, 2013), esp. 2–35.

[42] We see this attitude notably in the finding of Jesus in the temple, an occasion on which His Mother even seems to express a tender reproach: “Son, why hast thou done so to us? Behold thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing” (Lk 2:48). Yet only a few verses later, we are told that “his mother kept all these words in her heart” (Lk 2:51). Her reaction to the bewildering mystery of her Son is to take it into her soul and cherish it. What a lesson for us, who have been spoiled into thinking that everything should be immediately accessible, free of difficulty, and not demanding of us a long apprenticeship!

[43] It is true that Our Lord addresses His Mother as “Woman” from the Cross. However, this is not a generic label meant to replace her personal name, but a symbolic declaration of her role in salvation history, her being the New Eve and the mother of all the living, that is, the woman in whom the mystery of the Church is fully embodied, by whom it is perfectly achieved, and through whom it is perpetually nourished.

[44] See William G. White, “Modernity vs. Maternity,” Homiletic & Pastoral Review 97.10 (July 1997), 61–64, also available here.

[45] While tradition does not come from us, it does depend on us, in the sense that if clergy and laity do not transmit whole and entire that which they have received, God may allow it to perish in a certain portion of the Church on earth. See Joseph Shaw, “Does Tradition Preserve Us, or We the Tradition?”

[46] Benedict XVI hints at this rich identity of the Roman rite in the opening paragraphs of the Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum (July 7, 2007): “Among the pontiffs who showed that requisite concern, particularly outstanding is the name of St. Gregory the Great, who made every effort to ensure that the new peoples of Europe received both the Catholic faith and the treasures of worship and culture that had been accumulated by the Romans in preceding centuries. He com-manded that the form of the sacred liturgy as celebrated in Rome (concerning both the Sacrifice of Mass and the Divine Office) be conserved. He took great concern to ensure the dissemination of monks and nuns who, following the Rule of St. Benedict, together with the announcement of the Gospel illustrated with their lives the wise provision of their Rule that ‘nothing should be placed before the work of God.’ In this way the sacred liturgy, celebrated according to the Roman use, enriched not only the faith and piety but also the culture of many peoples. It is known, in fact, that the Latin liturgy of the Church in its various forms, in each century of the Christian era, has been a spur to the spiritual life of many saints, has reinforced many peoples in the virtue of religion and fecundated their piety.”

[47] See Pius XII, Mediator Dei, §61: “[A]ncient usage must not be esteemed more suitable and proper, either in its own right or in its significance for later times and new situations, on the simple ground that it carries the savor and aroma of antiquity. The more recent liturgical rites [he is speaking of the Tridentine period] likewise deserve reverence and respect. They, too, owe their inspiration to the Holy Spirit, who assists the Church in every age even to the consummation of the world. They are equally the resources used by the majestic Spouse of Jesus Christ to promote and procure the sanctity of man.” Pius XII goes on to condemn false antiquarianism.

[48] On this point, The Ottaviani Intervention has lost none of its incisiveness. Even though the flawed first edition of the General Instruction was revised, the rite that enshrined the reformers’ principles was left untouched. There is, of course, an abundant literature on the ways in which the new rite fails to respect the canons, anathemas, and pastoral recommendations of Trent and the determinations of other magisterial pronouncements. A good summary may be found in Sire, Phoenix from the Ashes, esp. 226–86. Michael Davies’ Cranmer’s Godly Order remains likewise a classic treatment of the subject.

[49] That the vast majority of the over 2,000 prelates who discussed liturgical reform and signed their names to Sacrosanctum Concilium had no intention whatsoever of endorsing a massive liturgical sea change is a fact acknowledged by all who have studied the Second Vatican Council in any detail. Indeed, they were reassured by the document’s explicit statement that “there must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing” (SC 23). Sacrosanctum Concilium itself exhibits the insidious scheming of Annibale Bugnini and his team in its many loopholes and in the systematic wiping-out of its internal references to preceding magisterial documents right before the final vote. Such actions are their own punishments and bring still others in their train. That, moreover, these same prelates could all accept only a few years later the unprecedented upheaval in the entire system of Catholic worship shows the extent to which a heady combination of 1960s revolutionism, ultramontanism, cowardice, groupthink, and wishful thinking can deceive even the elect. Fortunately Our Lord raised up the minor and major prophets the times demanded, who kept the flame of tradition burning in the midst of the descending darkness.

[50] It is true that we have some apprehension of nature and natural law—without it we could never recognize the truth of divine relevation. It is no less true, however, that our fallen condition occludes our vision and warps our judgment. As St. Thomas says, many important truths accessible to reason will only be discovered by a few of the brightest men, only after a long time, and with an admixture of error. God in His love reveals the truths we must know and the law by which we must live. These truths and this law are expressed in and inculcated by the traditional sacred liturgy: lex orandi, lex credendi.