The following talk was given on June 4, 2022, in Independence, OH (a suburb of Cleveland) at the invitation of Una Voce Greater Cleveland. As the talk fell on the Vigil of Pentecost, it includes frequent reference to the great mystery celebrated by this feast. The video of the lecture, with Q&A, is included at the end of the post.

Why Latin Is the Right Language for Roman Catholic Worship

Peter A. Kwasniewski

Cleveland, Ohio

June 4, 2022

The question of the language in which a Christian liturgy should be conducted is a much more complicated question than most people realize at first glance. To the extent that we have been brainwashed by rationalism, we tend to assume that the only purpose of speaking, of using words at all, is to communicate ideas between people. Language has a utilitarian function; this is its only justification.

Of course, it is true that we use words to convey ideas to one another. But language has loftier functions. For example, poetry pays attention to the beauty and sound and associations and intricate inner meanings of language; it is meant as a testimony to and a revelation of something of “the mystery of being.” That is why it is often harder to grasp, but more rewarding when understood, and, in the best poetry, always contains some element of the ineffable or inexpressible—the reaching toward a thought or a vision or an experience that cannot be captured in words.

Or consider nursery rhymes, lullabies, and nonsense songs. These are sung for fun or to little children to entertain them or to help them fall asleep. The communication of a definite meaning is not the point; it is about togetherness, comfort, reassurance, simple delight. Language here becomes more a vehicle of sentiment and feeling.

Or consider prayers offered by the Church to God: it is a good thing for the one offering the prayer to understand what he is saying, but since the prayer is from the Church to God, the purpose of it is not human comprehension—as if that is the goal—but humbly and efficaciously supplicating God. He, or His grace and blessing, is the purpose of the prayer, and so what matters most is the objective content, the goodness, of the prayer itself, not so much whether those saying it or those hearing it fully grasp its meaning. In his outstanding book The Traditional Mass: History, Form, and Theology of the Classical Roman Rite, which I will cite multiple times, Michael Fiedrowicz writes:

In order to understand the essence and meaning of a sacred language, it is important to be aware that language has multiple functions. First, it is a medium of communication that allows for the transmission of thoughts or information. Here intelligibility is vital. Beyond this, however, language is a form of expression. By means of language, man can give expression to his feelings and experiences, even his entire being. Thus, for example, singing a song does not convey information, but rather expresses sentiments, creates an atmosphere, and brings about fellowship. Considered from the standpoint of linguistics, prayer belongs more to the realm of expression than to that of communication. This applies not only to personal prayer, but also to collective prayer. Insofar as the sacred language in the liturgy is primarily directed toward God, it does not especially aim at imparting information in the sense of human communication. Here the language serves rather as a bridge between the profane world and the transcendent God. The sacred language, as a simultaneously human and stylized speech, seeks to create an atmosphere that both reflects and evokes a certain religious attitude in those who pray.[1]

To the extent that there is a definite content to be communicated, the use of Latin is by no means an insuperable barrier to comprehension. As Dr. Joseph Shaw explains:

Neither the inaudibility nor the use of Latin in practice creates a barrier of understanding between the worshipper and the liturgy, since members of the congregation can consult a hand missal, printout, or smartphone, to see exactly what is being said, translated into a wide variety of languages. It does, on the other hand, mark off the liturgy as something special and distinct from ordinary life. When we enter into the Latin zone, so to speak, we are entering into a spiritual space. In this way Latin powerfully reinforces the atmosphere created by the architecture and fittings of a church building, the special vestments worn by the clergy, the distinct type of music appropriate to the Mass, and so on…. The Latin of the Mass was never, in truth, the language of the street, or of the public speaker. Not only is it often flowery and poetic, but it is strongly marked by the influence of Greek and Hebrew, and makes extensive use of repetition and deliberate archaism. It was always intended to be what it is: a distinct, holy, language, to be used only in the liturgy.One does not have to understand the Latin text word by word as it is spoken to perceive—and be moved by—the solemn character with which it clothes the liturgy. The meaning of the text can be immediately available to the worshipper in printed form, but the impression made by the form of the text, the fact that it is proclaimed in an ancient, sacred language, of unique grandeur and gravity, is also of considerable value.[2]

Today, of course, is the Vigil of Pentecost—a feast so great in the eyes of the Church that it was celebrated for eight days (i.e., as an octave) in the Latin rite of the Catholic Church going back to the late sixth century, a custom that continues today wherever the ancient form of the Roman rite is used. A friend once told me he had expressed his love of the traditional Latin Mass to a certain deacon, who countered in a huff: “Pentecost shows that the apostles spoke to everyone in their own language—and it wasn’t Latin.” This liturgical misinterpretation of Pentecost and the gift of tongues, which one hears now and again in different forms, deserves a response.

What the Acts of the Apostles shows is that the apostles preached to the people in many languages. There is nothing in the Pentecost story about worship in the temple or synagogue, or the Eucharistic liturgy and the Divine Office that developed out of them and supplanted them. And as far as I know, it’s always been the custom to preach in the vernacular at Latin Masses, except in highly specialized academic contexts. The gift of tongues is a gift for the sake of evangelization, apologetics, and catechesis—not specifically for liturgical worship.

Moreover, it’s always worthwhile to point out that as useful as preaching is, the Church developed over the centuries many other modes of expression that proved to be as effective or even more effective in evangelizing. Let me offer you an example. In a book called Truth in Many Tongues, Daniel Wasserman Soler studies how missionaries made use of pagan vernacular languages in the sixteenth-century Spanish empire. The author states:

We must leave behind a widespread modern assumption . . . made famous in the Protestant Reformation . . . that the written and spoken word constitute the fundamental and best way for people to learn about religion…. The first bishops of Mexico City, Guatemala, and Oaxaca indicated to King Charles I that sermons may not have been the key to the conversion of the American natives: ‘We confirm, Your Majesty, that the Natives are edified very much by devoted service, ceremonies, and ornate artwork, perhaps even more than by sermons.’ Thus in the minds of many clerics, the combination of vivid artwork, the fragrant smell of incense, the sense of inclusion in a community, and the example of a pious, Christ-like cleric together could prove a more powerful force for religious conversion than preaching alone.

In a way, it is perfectly obvious once you state it, but there are so many people today who, in the grip of an unconscious rationalism, do not recognize how much is conveyed through non-verbal language, as well as through the emotional and supra-rational elements of language itself!

Language is never “merely” language; its cultural history, the traits and associations of classic works composed in it, the very sound of it falling on the ear—all of this is borne along with the language, and often delivers as much impact as, or even a greater impact than, its conceptual content. The moment we hear “In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen. Introibo ad altare Dei,” we are immediately placed in a different zone; it’s almost like when the angel takes up the prophet Habakuk by the hair of his head and carries him off to Babylon, except that it’s in the opposite direction: the worshiper is carried from the Babylon to the Holy Land, from the valley of tears to the holy of holies.[3] Observes Fiedrowicz:

Here the Church also proves to possess a thorough understanding of human nature, as in this way she helps her faithful to detach themselves from their everyday language, where each word recalls profane realities, and to feel, even sensibly, that “wholly Other” sought by all piety…. The sacred language spreads a delicate veil over the truths of the Faith, which protects the holy mystery and eludes hasty comprehensibility.… A language that is not commonly understood suggests to the faithful that they stand before a mystery that eludes total transparency. In contrast, vernacular language counterfeits an understanding that is absolutely not real.[4]

In the past sixty years of wayward liturgical reform and abuse, far too much emphasis has been placed on the vernacular (as in, a particular language spoken by a group of people), as if it is somehow the magic key to participation. For one thing, any vernacular immediately excludes everyone who does not speak it—and that includes people who speak a lower register of the language, as well as that forgotten group whose education equips them to grasp higher registers as more appropriate in worship, and who will be vexed by translations into flat, dull, gray modern tones.[5]

What the reformers seemed to have forgotten is that there is a universal non-verbal vernacular accessible to all mankind: the language of symbols. Be they colors, actions, sounds, smells, or other religious signs, this vocabulary has an immediate although at times perplexing effect on the consciousness. It shows us reverence without talking about it; it shows us mourning or rejoicing without spelling it out in trite or laborious words. A black chasuble, unbleached candles, a catafalque, and the repeated refrain “Requiem aeternam” instantly tell me more about the meaning of a liturgy for the dead than a hundred books written on the subject.

Yes, liturgical Latin is “strange” in the sense that it is not something everyday, familiar, easy, at our level or at our disposal; it evokes the transcendence and majesty of God, the universality of His kingdom, the age-old depths of the Faith. But over time, we identify this set-apart language as a sign of honor, we experience it as a promoter of reverence, and we find in it an invitation to prayer. When we dive into a pool, the moment we hit the water, we know—not just rationally, but viscerally—that we are in a new medium and we must swim. So too when we hear the Latin chant or recited prayers, we know we are in a new medium and we must pray.

So far from being a peculiar custom of the Western Church, the custom of employing a sacred language in religious rites is already prominent in salvation history, as Shaw points out:

The tradition of Gregorian chant goes back to the Temple in Jerusalem, where we are told professional singers were employed (2 Chron 5:15); the use of Latin recalls the use of Hebrew as a sacred language, when the language of the Jewish people had become Aramaic; the traditional liturgy’s emphasis on priest, altar, and sacrifice is redolent of the atmosphere of ancient Jewish worship, something sometimes noted by Jewish converts…As Jews, they [the Apostles] were brought up to pray and sing the Psalms in Hebrew, as well as in their mother tongue. No word of criticism of sacred languages is to be found in Scripture, and the earliest liturgies were by no means composed in the language of the street. In Greek-speaking areas, the Church was able to employ the sacred register created by the Septuagint translation of the Bible: a distinct form of Greek already two centuries old and filled with Hebraisms. Latin liturgy did not emerge until Latin translations of the Bible had created something equivalent, and, when it did, we find a liturgy in a sacred Latin with a specialized vocabulary, replete with archaisms, loan-words, and other peculiarities; similarly, liturgical Coptic is an archaic language larded with Greek terms and written in Greek letters. As for Church Slavonic and the language of the Glagolithic Missal, their origins and history are not reducible to the simple idea of the “language in use at the time,” and, in any case, they quickly become liturgical languages for people not able to understand them. They remain culturally connected to the peoples they serve, but not readily comprehensible by them.[6]

We see, in fact, that every ancient Christian church developed a sacral language and idiom for worship: the Greek Orthodox Church still uses koine Greek, the Russians use Church Slavonic, the Ethiopians use Ge’ez, the Copts use literary Coptic, etc. The fact that some Eastern Christians have adapted to a modern vernacular is an historical anomaly that should by no means be taken as normative, even if we do not need to condemn it either. The Eastern Christian sphere has always seen far more linguistic diversity than the Western sphere, which remained stalwartly committed to Latin for over 1600 years—a longer time with a single language for worship than can be found in any other religious tradition except for the use of Hebrew by the Jews and the use of Greek by the Greek Orthodox. It is hardly surprising that a belief grew up that the three great sacred languages are Hebrew, Greek, and Latin, on the basis of the threefold inscription that Pontius Pilate placed on the Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Indeed, the use of a special set-apart sacred language for religious actions goes well beyond the borders of Judaism and apostolic Christianity, as Fiedrowicz explains:

The phenomenon of a sacred language is found in all religions. Such a language was used by the Greek oracles of ancient times and can be found in ancient Roman pagan prayers, whose formulas date back to distant antiquity, occasionally having become unintelligible even to the priest himself, though still used in order to remain true to ancestral tradition. At the time of Christ, the Jews used the language of Old Hebraic for their services, though it was incomprehensible to the people. In the synagogues, only the readings and a few prayers relating to them were written in the mother tongue of Aramaic; the great, established prayer texts were recited in Hebrew. Although Christ adamantly attacked the formalism of the Pharisees in other respects, He never questioned this practice. Insofar as the Passover Meal was primarily celebrated with Hebrew prayers, the Last Supper was also characterized by elements of a sacred language. It is therefore possible that Christ spoke the words of Eucharistic consecration in the Hebrew lingua sacra. Other world religions also recognize sacred languages that differ from everyday idioms. The Muslims use classical Arabic for their prayers. The Buddhists employ Pali, and the Hindus Sanskrit.Even within Christianity various dedicated languages of worship have developed. Thus the Orthodox Greeks celebrate their liturgy in ancient Greek and the Russians in Church Slavonic. In addition, there is the use of Armenian, Coptic, and Syrian. Though originally these were certainly the living, vernacular language, over the course of time they grew ever more distant from everyday speech and finally assumed the character of a proper language of worship. Even Anglican services use the melodious Elizabethan English found in the Book of Common Prayer.[7]

This remarkable unanimity of practice across thousands of years and across every continent and culture, even those furthest removed from one another with no contact until much more recently, indicates a profound common awareness that wells up from human nature confronted by the evidence of an ultimate divine source of reality or an invisible spiritual dimension of reality to which we must relate in a different way than we relate in the business or pleasures of ordinary everyday life. Fiedrowicz puts his finger on the underlying reason:

If sacred languages existed in numerous cultures and almost all epochs of history, and still continue to exist, this fact is an expression of a fundamental human need. In the background stands a particular religious experience that shapes and changes speech and language. It is the experience of something supernatural, divine, transcendent, and wholly other, to which man seeks to respond by using a language that differentiates itself from the form of everyday speech by means of a sacred stylization. Here lies the origin of the so-called hieratic or “priestly” languages. Far from creating a language barrier, the sacred language calls to mind that religion has “something else” to say to man. The sacred language prevents man from dragging the divine down to his own level, and instead lifts man up to the divine, which it does not, however, reveal and expose completely to the human understanding, but instead indicates as a mystery.[8]

The same author, himself a priest, a master of Latin and Greek classics, and a professor of Patristic thought, goes on to identify “the characteristics of a sacred language”:

(1) a conscious distancing from the words of colloquial language, which makes the “complete otherness” of the divine felt; (2) an archaizing or at least conservative tendency to favor antiquated expressions and adhere to certain speech forms from centuries ago, as is well-suited for the worship of an eternal and unchanging God; (3) the use of foreign words that evoke religious associations, as, for example, the Hebrew and Aramaic forms of the words alleluia, Sabaoth, hosanna, amen, maranatha in the Greek books of the New Testament; and finally, (4) syntactic and phonetic stylizations (e.g., parallelisms, alliterations, rhymes, and rhythmic sentence endings) that clearly structure the train of thought, are memorable and allow for easy recollection, and strive for tonal beauty.[9]

Levels of language

We will understand better why Latin is the correct and fitting language of the Roman Catholic liturgy if we begin with a truth everyone knows from experience. Any time a language is spoken, it is spoken in what linguists call a ”register,” which means a level of formality, polish, or sophistication, ranging from rough, casual, or slangish at the lower end, to intricately-wrought poetic diction at the higher. Individuals can use their native language in various “registers” depending on circumstance and education. Analogously, we may say that languages as such present themselves in different “registers.”

At the lowest level are slang and pidgins (a pidgin is defined as a “grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from several languages”).

Higher up are ordinary vernaculars. A notable difference at this stage is that linguistic expectations are significantly higher in regard to usage, pronunciation, grammar, style, and so on. What people get away with in slang is not “allowed” in many everyday contexts.

Higher up still are so-called prestige languages. Of course, these are native languages for some people, but they are chosen as second or third languages by many others due to their reputation. French has been a prestige language for over a thousand years. For many centuries Latin was a prestige language in Europe, as Classical Greek was for the Romans. Note that linguistic expectations here are even higher, as these languages are supposed to be a sign of education, culture, urbanity. A 19th-century Russian spoke French to show that he was cosmopolitan and upper-crust.

Higher up still, and with the highest level of expectations, are reserved languages. The examples that come to mind were all prestige languages at one time, and now their use is almost entirely for religious purposes: Hebrew, Classical Greek, Latin, Syriac, Old Church Slavonic, and outside of Christianity, Sanskrit and Quranic Arabic. These languages are revered because they are languages in which we express our reverence; they have become reserved to (or at any rate specially associated with) sacred contexts.

One may also distinguish between a lingua franca and a prestige language. A lingua franca is adopted by speakers of other languages as a common means of communication for practical reasons, as when an Italian and a Japanese do business in English. But a prestige language is studied in addition for reasons of culture. One might, in other words, choose to study a prestige language even when there is no practical need to do so. Since reserved languages always come from the ranks of prestige languages, they are not used simply for reasons of practicality. In short: the lower registers of language tend to be more practical in nature, while the higher registers are more cultural, ceremonial, and numinous.

Language is not merely a matter of practical communication; it is also an embodiment of thought and a work of art, a very high expression of our rationality, spirituality, and transcendence. People do not write poetry, for example, just for practical reasons. Part of what makes a prestige language prestigious is the depth, subtlety, and amplitude of expression found in it, owing to its rich history; and this is even more true of reserved languages, which, having been prayed with for centuries or even millennia, are saturated with sacral associations. The language has, in a sense, fused with the action, the rite, the content. It has itself become a symbol supporting and adorning other symbols.

Having grasped these distinctions, we see that the transition of Latin from being a vernacular to being a prestige language to becoming finally a reserved language is a natural one, paralleled by other languages, in a phenomenon seen throughout the world and throughout history.

Now, when a sacred liturgy is already conducted in a reserved language, any change from it is necessarily going to be a step down, linguistically speaking—perhaps a big step down, as we would normally be looking at “vernacularization,” which is a lower register. Not only will a great deal of the conceptual content of the reserved language be lost, but its entire ethos, atmosphere, resonance, symbolic association, and consecrated status will be lost as well. One ends up losing far more than a language; one loses a culture, a psychological space, a spiritual environment, an entire world, with its historical rootedness and its unique qualities and its powerful assets.

It is striking to consider what the Roman Pontiffs have taught on the subject of Latin. In 1922 Pope Pius XI wrote: “The Church . . . of its very nature requires a language that is universal, immutable, and non-vernacular.” In 1947, Pope Pius XII stated in his encyclical Mediator Dei: “The use of the Latin language, customary in a considerable portion of the Church, is a manifest and beautiful sign of unity, as well as an effective antidote for any corruption of doctrinal truth.” In 1962, right on the eve of the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII solemnly promulgated an Apostolic Constitution Veterum Sapientia in defense of Latin as the proper language for Latin-rite church studies, documents, and liturgy. He says:

The Church’s language must be not only universal but also immutable. Modern languages are liable to change, and no single one of them is superior to the others in authority. Thus if the truths of the Catholic Church were entrusted to an unspecified number of them, the meaning of these truths, varied as they are, would not be manifested to everyone with sufficient clarity and precision. There would, moreover, be no language which could serve as a common and constant norm by which to gauge the exact meaning of other renderings. But Latin is indeed such a language. It is set and unchanging. It has long since ceased to be affected by those alterations in the meaning of words which are the normal result of daily, popular use…[T]he Catholic Church has a dignity far surpassing that of every merely human society, for it was founded by Christ the Lord. It is altogether fitting, therefore, that the language it uses should be noble, majestic, and non-vernacular. In addition, the Latin language “can be called truly catholic.” It has been consecrated through constant use by the Apostolic See, the mother and teacher of all Churches, and must be esteemed “a treasure...of incomparable worth.”The employment of Latin has recently been contested in many quarters, and many are asking what the mind of the Apostolic See is in this matter. We have therefore decided to issue the timely directives contained in this document, so as to ensure that the ancient and uninterrupted use of Latin be maintained and, where necessary, restored.

It deserves mention that this Constitution, although ignored by the progressives and modernists and even, after a while, by the conservatives, was never rescinded or contradicted by later popes in any document of comparable status. The universal truths it contains remain no less true in spite of the unwillingness of churchmen to implement its practical policies—just as the universal truths contained in the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum remain true regardless of the practical efforts of Pope Francis or Archbishop Roche to suppress the traditional liturgy of the Roman Church.

We might be tempted to rush past the claim made by Pius XII and John XXIII that the use of Latin safeguards orthodoxy, but it deserves a moment’s attention. They are referring, of course, to the traditional Latin formulas used in the liturgy, in the Vulgate, in the Western Fathers of the Church, in the canons and decrees of ecumenical councils, in canon law and in other magisterial documents. This body of Latin teaching is astonishingly unified and consistent across centuries. Anyone who knows Latin well can pick up almost any Latin text from a period of over two thousand years and understand it. This record of continuous worldwide use of a single stable language is practically unique in human history and supports what the popes are claiming on its behalf.

The translation of liturgical books into the vernacular has, on the other hand, demonstrated the claim negatively: we are drowning in examples of dumbed-down translations, of erroneous and theologically problematic translations, and constant fights over the register of language to be used in official translations. The awful version of the Bible inflicted on American Catholics, the New American Bible, isn’t even written in proper English; as Anthony Esolen says, it’s written in “Nabbish.” Whether one is talking about doctrinal texts or liturgical texts, the vernacular tends to be a non-stop headache, earache, and heartache.[10]

Latin is a crucial part of Catholic Tradition—not alongside it, but within it; indeed, it is that by which Tradition was transmitted in the Western world. It is part of the way God has provided for His Church. Even if modern people all agreed that Latin should be abolished completely, it would not cease to be part of Tradition: this is an unarguable and unchangeable fact. We might compare it to celibacy. The ecclesiastical law that a priest cannot marry derives from Tradition. Nowadays many “experts” say they “know” that celibacy is responsible for low numbers of priests. Next to priesthood for women, celibacy is a favorite target for modernists, and every “modern” Catholic is supposed to be opposed to it. Yet it is part of Tradition, and as such irreversible. Latin is very similar to celibacy in this regard. While it is used in the liturgy not by divine law but by Church law, it nevertheless is part of Tradition (as are Greek, Slavonic, Syriac, Armenian, etc., for the Eastern churches) and should therefore be preserved, regardless of our personal modern opinions.

The error that led to the abolition of Latin was neoscholastic and Cartesian in nature—namely, the belief that the content of the Catholic Faith is not embodied or incarnate but somehow abstracted from matter. Thus, many Catholics think that Tradition means only some conceptual content that is passed down, irrespective of the way in which it is passed down. But this is not true. Latin is itself one of the things passed down, together with the content of all that is written or chanted in Latin. Moreover, as we have seen, the Church herself recognized this point on a number of occasions in singling out Latin for special praise, recognizing in it an efficacious sign of the unity, catholicity, antiquity, and permanence of the Latin Church.

Latin thus possesses a quasi-sacramental function: just as Gregorian chant is “the musical icon of Roman Catholicism” (Joseph Swain), so is Latin its “linguistic icon.” Liturgical reformers in the grip of rationalism treated Latin like a mere accident, as if it were the dispensable packaging of a product. In reality, it is more like the skin of a person. The skin is superficial, but if you take it away, the result will be an ugly mess. Which brings me to Vatican II and the Novus Ordo.

Many Catholics throughout the world—including, apparently, bishops and cardinals—seem to be unaware that the teaching of Pius XI, Pius XII, John XXIII, and other popes was deliberately echoed and confirmed by the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium: “The use of the Latin language is to be preserved in the Latin rites” (36.1); “steps should be taken so that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (54); “in accordance with the centuries-old tradition of the Latin rite, the Latin language is to be retained by clerics in the divine office” (101.1). The Council did open the door to a greater use of vernacular, but it did not mandate the vernacular, and clearly the constitution was passed by a huge majority only because the bishops had been reassured that there would be a moderate reform, not a revolution.

Contrary to the claims of Pope Francis, most of the bishops at the Second Vatican Council, if you study their speeches, actually supported the retention of Latin, which is why they voted for it in the final document.[11] We know now, thanks to the careful research of historians like Yves Chiron, that Bugnini who spearheaded the writing of Sacrosanctum Concilium had, already before the Council began, successfully colluded with his teammates to execute just such a revolution once the Council had ended, and in a Machiavellian manner counseled the use of vague, ambiguous, and open-ended language with plenty of loopholes that could be exploited later on—which is exactly what happened.

So, while Vatican II officially reaffirmed Latin in the liturgy and made a cautious opening to some use of the vernacular, especially in instructional parts, what came afterward, with Paul VI’s support, neutralized or neutered it, and Paul VI’s departure from both Tradition and the Council has never been opposed by any of his successors. This is one of the reasons why Latin will never reappear in any significant way in the Novus Ordo: Paul VI waved goodbye to it, and only traditionalists, who adhere to the preconciliar liturgy, have dared to question his good judgment in undertaking a wholesale reinvention of the Catholic Church’s divine worship.

The Novus Ordo was created for maximum intelligibility, maximum ease of understanding. It was supposed to remove every possible barrier to the comprehension of the faithful: they are supposed to see, hear, and know everything that is being said and done at every moment, instantly and without preparation or reflection. This lecture is not the occasion for me to explain what is wrong with this model or the presumption behind it, but suffice it to say that never in the entire history of apostolic Christianity East and West, and never in the history of world religions, has this been the way anyone has ever thought about divine worship. In any case, if such immediate and total transparency is the goal to be sought, everything is going to have to be simplified, put into the common language, and made visible and audible. Thus the priest will be turned to face the people, he will have a microphone, there will not be much silence, only one thing will happen at a time, etc.

If this is your paradigm for worship, then it’s rather obvious that Latin—and Gregorian chant, too—will have no place in it, at least for 99% of congregations. The Novus Ordo in Latin “falls between two stools” (to use a phrase of Joseph Shaw’s): it has neither the instant accessibility for which it was designed, nor the grandeur, solemnity, symbolic richness, and ceremonial depth of the Tridentine rite, all of which augments our awareness of mystery and our receptivity to truths that cannot be put into simple linguistic packages.

In short, Latin befits the old Mass like stained glass befits a Gothic church, or gold befits a chalice, or silence befits the Roman Canon; it doesn’t work with the design principles of the new Mass.

The accessibility of the Novus Ordo is, however, illusory, deceptive, in two ways. First, its verbal approach tricks us into thinking that we have understood or that we are capable of comprehending divine worship and the mysteries of Christ. Because its mode of active participation is very much on the surface, about voices and bodies in motion, we can easily pass through an entire such liturgy without having once pondered or interiorly prayed, without having suffered wonder, bewilderment, or awe. This is not a problem the Latin Mass has, in which there are frequent and diverse provocations to the acts of prayer, and where the intended participation is more of the heart and mind. Second, it is accessible only to those who speak a given vernacular language, and who can hear it and follow it. In a multicultural world, and with factors like inadequate elocution, poor sound systems, or ambiant noise, the curse of Babel can quickly fall down on us. I would like to focus on this point for a moment.

Fr. Louis Bouyer pointed out: “Every religious tradition represents language as a gift of the gods that makes society possible and continues to hold it together like a thread. Conversely, Genesis sees in the fragmentation of speech into mutually incomprehensible languages a curse from heaven upon a sinful society.”[12]

The first Christian Pentecost, nine days after Our Lord ascended into heaven, is presented in the Acts of the Apostles as a reversal of the tower of Babel. The original curse upon ambitious man was to divide his progeny into a thousand languages. Even if the rich poetic fruits of multiple languages can be counted a blessing willed by God, the difficulty and often impossibility of common discourse among rational animals is unquestionably a curse. This curse is renewed whenever we are confronted with a liturgy in which the use of some vernacular that is foreign to us effectively says: “This is not for you; it’s only for them, for that demographic.”

When liturgical traditions develop a common language of public worship, it is a symbolic return to the prelapsarian condition of the Garden of Eden, when human beings would have spoken only one language. In the Latin liturgy, we are not confronted with a foreign vernacular that excludes us; rather, we hear the sound of a single voice that belongs to the Church at prayer, welcoming all nations and peoples into one celebration.

In some dioceses, the Novus Ordo Mass can be found celebrated in fifteen different languages, and each language group is an island unto itself, hardly mixing with other groups. But there are multi-ethnic and multilingual Latin Mass parishes where the Mass itself is truly the unifying force for all the subgroups, bringing them together in fraternal relations, and allowing them to mingle socially as well. How many of us have been to a Latin Mass and seen whites, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, various ethnicities and nationalities, all gathered in one act of Catholic, that is, universal, worship? As John XXIII pointed out, Latin belongs equally to everyone and to no one in particular. The Latin liturgy in history has always been an ethnically and culturally integrating force; it continues to build those bridges today.

I had a potent experience of this not long ago when visiting Poland for a conference. In spite of my surname, which is as Polish as pierogi and kielbasa, I hardly speak a word of Polish, which is widely considered a very difficult language to learn. For days I had been surrounded with unintelligible noises to which everyone else could respond and I could not (thankfully the conference provided me with earphones broadcasting a simultaneous English translation). One morning on my visit I walked with a group of friends to Wawel Castle, one of the most beautiful and historic places in the city of Krakow, to reach the side chapel where Low Mass would be offered by a priest of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter.

We arrived just as Mass was starting. The comforting words of the Latin fell like a refreshing rain on my ears, or like a ray of light piercing the impenetrable fog of the foreign language of the country outside. We were in God’s country now. The priest said the Mass deliberately and with an easily audible voice, so that I missed not a single word. Sadly, due to the clumsy and illicit provisions of Traditionis Custodes, the Lesson and Gospel were given only in Polish, which suddenly plunged me into the fog of unintelligibility again, and reminded me of how the vernacular not only includes the locals but excludes the stranger. It was the only part of the Mass that lost its world-embracing catholicity in favor of a narrow localization. At the conclusion of the Gospel the server said: “Laus tibi Christe,” and all was well again. The remainder of Mass alternated between moments of Latin that bobbed up above the surface of silence, and the enveloping quiet in which the Word became flesh anew, as it were, upon the altar, in the power of His Incarnation, Passion, Death, Resurrection, and Ascension.

That Mass in the Wawel side chapel was a perfect experience of the liturgy as synchronic and diachronic: synchronic, because I felt instantly and immediately at home in the very same liturgy said all across the world, wherever tradition is treasured—an experience I’ve now had dozens of times on my travels; diachronic, because it was substantially the same liturgy that had always been said on most of the altars of Christendom in the West for centuries. Alcuin of Charlemagne’s court, St. Anselm of Canterbury, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Edmund Campion, St. Charles Borromeo, St. John Vianney, St. Vincent de Paul, St. Padre Pio, St. Charles de Foucauld—all would have been at home. With the traditional Latin Mass, across the ages and around the world, one is always at home. The miracle that, for some sacred moments at least, undoes the chaos of Babel demands the strong stability and inner coherence of the great Roman liturgy whose language gives to Latin-rite Catholics their very name.

Our native language, our “mother tongue,” comes from our earthly mother: when we are living inside her womb, her voice is the first we hear, and when we come forth into the world, we hear the same voice upon her breast. Our everyday vernacular is something we are, in a sense, equipped with by nature, by effortless immersion in the family culture. This language represents the natural order in which we live and move and have our natural being.

Now, even as baptism or rebirth comes to the Christian from outside (for, as Joseph Ratzinger writes, “nobody is born a Christian, not even in a Christian world and of Christian parents. Being Christian can only ever happen as a new birth. Being a Christian begins with baptism, which is death and resurrection, not with biological birth”), so, too, the sacral language in which we worship comes to us from outside, from Holy Mother Church, who teaches us a new Christian language—a spiritual ”mother tongue”—which represents the supernatural order in which we live and move and have our supernatural being. Latin-rite Catholics have a sacral language that comes to them “from outside,” just as baptismal rebirth does.

The Christian liturgy should somehow convey to us that, when we enter the Lord’s temple, we are speaking not with a merely natural speech, but with a supernatural speech, a language of saints, angels, and God. Obviously, this language does not have to be Latin—as noted above, there are many sacral languages used in traditional apostolic rites—but it should not be the everyday vernacular of the hearth and the marketplace, or even the technical speech of academic disciplines. It should be set apart by centuries of use consecrated to divine worship; in this way, it helps worshipers to set aside earthly cares and consecrate symbolic portions of our time to God alone. A traditional liturgical language is a reminder that our supernatural adoption into the family of God is more fundamental and more ultimate than any earthly family, citizenship, nation, or race.

Most importantly, something the Catholic Church in the West has practiced for over 1,600 years—something that nearly all of our thousands of canonized saints personally practiced—cannot be condemned without denying that the Holy Spirit has been guiding the Church into the fullness of truth (cf. Jn. 16:13). The Holy Spirit who gave linguistic utterance to the apostles as they preached to all the nations also gave liturgical Latin to the Western Church as her inheritance, handed down from century to century with ever-increasing veneration. What was established by choice was confirmed by custom and preserved by piety. The forms of worship developed over centuries with a richness of content and texture that made it increasingly unlikely that it could ever be readily duplicated in or adapted to a foreign idiom; this made it all the more precious and worthy of cultivation. Against the backdrop of experiments in vernacularization from the mid-twentieth century onward—experiments that could be called, with more justice, Babelization—an ever-increasing number are coming to see that this unique and unitive Latin heritage remains precious and worthy of cultivation today.

Nor should we overlook the crucial fact that no modern vernacular is capable of conveying all that is contained in the traditional Latin prayers. Every translation is a betrayal; all the more so when we are looking at a vast treasury of over 1,600 years of liturgical Latin. A hand missal can give the gist of the content fairly well, but the Latin prayer says more, says it better, more subtly and fully and strikingly. Does this make a difference? By all means. The one we are principally addressing is God, and how we speak to Him matters. When we offer Him solemn, beautiful, highly-valued and saint-spoken prayer, it is pleasing in the way that an unblemished lamb is pleasing—in the way that the unblemished Logos offered on the Cross was pleasing. The very fact that countless holy men and women had the very same words on their lips over the centuries endows them with a special efficacy. St. Mectilde of Hackeborn says that the court of heaven rejoices whenever it hears the same words it prayed while on earth.

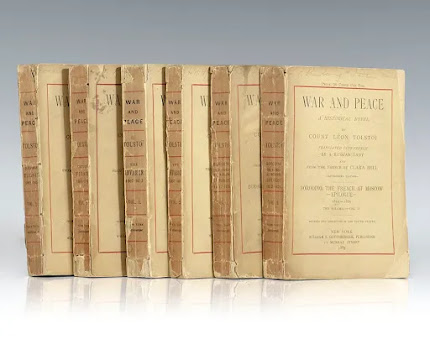

|

| Libraries of the world are full of untranslated Latin manuscripts (this is Trinity College Dublin) |

Conclusion

One way we can see the fallout of the abandonment of Latin is to consider the intellectual and theological effects. The vast majority of Western Christian writings in all areas—theology, exegesis, canon law, liturgy, hagiography, etc.—was composed in Latin, and the vast majority of this literature has still not been translated. The radical progressives who waged war against Latin in the mid-20th century knew very well what they were doing: they wanted to blow up the bridge that connected Catholics with their heritage, their tradition, their collective memory. The vaunted “modernization” of the Church could be carried out only if the past were forgotten, sealed inaccessibly behind a wall of incomprehensibility. The loss of Latin has therefore had ramifications far beyond the sanctuaries of our churches, even if that is where we most notice its presence or absence. Heresy thrives on a combination of amnesia, anarchy, and novelty. The liturgical crisis is only one part of the larger crisis of Catholic identity, which has more to do with language than most people realize.

Following on this point, I think it’s important for Catholics to realize that all of us should learn some Latin. It does not lose its historic role, special character, and sacred function if we do understand it as a language (mystery is not the same as mystification). When I understand the Latin of the liturgy, it doesn’t make it any less wonderful; on the contrary, one’s appreciation grows because one can savor its meaning and beauty. This is not necessary for fruitful worship, but it is a real advantage, and one that we should care to acquire. Latin was once a standard subject for all Catholic students and many individuals learned it to a high degree, even those who did not become priests or religious. If we care about our tradition and our heritage, we will make sure this language is included in our homeschool and private school curricula.

Recall that Hebrew was a dead language until the Zionist movement and the State of Israel revived it as a spoken language; today millions are fluent in it. Moslems study classical Arabic because they value their heritage. How embarrassing, how shameful it is that Catholics care far less than Jews and Moslems for a heritage that is immeasurably truer, better, and more glorious than that of either the Jews or the Moslems![13]

If anyone is to blame for this abysmal state of affairs, it is the hierarchy of the Church, shepherds who, contrary to their divine vocations, did not faithfully hand on the tradition that was given to them, and who have barely lifted a finger to correct a catastrophic cultural collapse.

Practically speaking, it is not difficult to acquire some basic facility with the Latin language as used in the liturgy. Simply by assisting at Mass and other ceremonies on a regular basis and using a hand missal, we will begin to pick up a rought-and-ready knowledge of vocabulary. Let’s be honest: the Gloria and the Credo are not hard to follow! The more zealous could pick up a good Latin instructional book or enroll in an online course. Happily there are already a good many people out there who are reviving the language, including in its spoken form. It should go without saying that children above all ought to learn Latin, since language acquisition is, generally speaking, much easier for children than it is for adults. Singing Gregorian chant, whether informally at home or as part of a choir, is an important and enjoyable way to gain some acquaintance with the treasury of ecclesiastical Latin. I recommend, for example, singing the seasonal Marian antiphons at home as part of evening devotions. Those are the Alma Redemptoris Mater, the Ave Regina Caelorum, the Regina Caeli, and the Salve Regina.

We must not be afraid to assert boldly that it is good and fitting and optimal to use Latin for the sacred liturgy, that is, the solemn, public, formal, official worship, of the Roman Catholic Church. The reasons for its use are so numerous and overwhelming, the substance and authority of tradition are so unanswerable, that there is no way to escape the conclusion that retaining Latin is a serious obligation before God and abandoning it is a serious deviation from His liturgical Providence. In the midst of cultural diversity, the Catholic Church had the wisdom to recognize the spiritual power of central elements of unity that bring us together in confessing the one true Faith and paying homage to the Most Holy Trinity. We can hope and pray that our Church leaders will, over time, take steps to recover what was foolishly squandered in shortsighted reforms. We, for our part, are able to show our gratitude to God by retaining and promoting the sound traditions of the Latin Church.

NOTES

[1] Fiedrowicz, Traditional Mass, 155.

[2] Shaw, How to Attend the Extraordinary Form, 26–28.

[3] In terms of the “sacred atmosphere,” one might add one that the concentration, discipline, and seriousness of the congregation at a traditional Latin Mass is supported by, and in turn supports, the ambiance created by and within the liturgy, in a classic “feedback loop.” As with the chicken and the egg, there is an answer to what comes first: it is the objective nature of the liturgy and its ceremonies, rubrics, music, which explain that behavior and continue to give rise to it.

[4] Fiedrowicz, 163, 164, 165.

[5] This group is quite naturally attracted to the Anglican Ordinate liturgy, if they can find it.

[6] https://www.hprweb.com/2020/02/the-novus-ordo-at-50-loss-or-gain/.

[7] Fiedrowicz, 153–54.

[8] Ibid., 154.

[9] Ibid., 154–55.

[10] The war opened with Traditionis Custodes is about so much more than the TLM. Francis is attempting to eliminate a whole way of being Catholic, even for people who never go to the TLM. The English liturgist Clifford Howell was wont to say that the use of vernacular in the Liturgy was pointing towards a new world order that couldn’t otherwise be expressed coterminously with Latin. I realize now that what he meant is that essentially the new liturgy is a social movement based on the wholesale rejection of the Catholic worldview. The Old Mass is too off-message now to be allowed to continue.

[11] See for examples: https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2017/09/the-council-fathers-in-support-of-latin.html.

[12] Invisible Father, 47.

[13] Our general lack of interest in our sacred heritage rises up to condemn us the way that Jesus said the queen of the south will rise up in judgment on the Jews because she came a long way, made a great effort, just to see Solomon—and what effort do we make to see into the gifts God has given us?

Full video with Q&A:

.jpg)