This is the first part of a lecture given yesterday at Saint Francis de Sales ( Mableton, GA)

Introduction

On November 5th 1880, the French army took the field and prepared to launch a battle that, today, nearly everyone has forgotten. It was a "great victory" for the French Republic, yet it never appears in the official History books at school unlike the great victories of the Nation such as Tolbiac, Marignan, Fontenoy or Austerlitz. Under the command of General Guyon-Vernier, one infantry regiment, five cavalry squadrons and a few artillery cannons began a three day siege. 2000 soldiers were ready to fight. The enemy was… the Abbey Saint-Michel de Frigolet, in the south of France, occupied by 37 good monks.

What was going on in France at this time, the eldest daughter of the Church and the Kingdom of Mary? Why did the Government send out its army to confront a little religious community?

It is important to note that the siege of Saint-Michel de Frigolet was not an isolated case, but only one episode among many. The Decree of October 16th 1880, three weeks earlier, ordered the eviction of all the religious communities in the country that were not authorized by the Government. When the superintendent mandated by the Government arrived at the monastery to read the notice of expulsion, the Superior of the Abbey, Reverend Father Boulbon informed him that his community, in all humility, would not be distinguished from all the other religious communities that had resisted the violence: the monks would stay! Thousands of faithful came to support the monks. It is by force that the police and the army entered the monastery. The monks were entrenched in the conventual church, when the forces’ orders arrived after having knocked down the doors and gates. Father Boulbon read a declaration of protest and finished with these words to the superintendent: “It is my duty to inform you that you and your constituents come within the provisions of a major excommunication reserved to the Pope.” Then the monks were escorted by the gendarmes while the dragons scattered the crowd as they sang the famous canticle of the Catholic Provence: Provençau e Catouli.

The same scene was repeated in 1903 when an infantry battalion and two dragon’s squadrons arrived to bolster the police forces and assist them in the expulsion of the Carthusian monks of la Grande Chartreuse. The entire local population came to defend their monks. They were 5000 in number praying the rosary and singing canticles during the night of April 28th. As the army arrived the crowd began to sing the Marseillaise and to shout: “Vive l’armée ! Vive les chartreux ! Vive la liberté !” (Cheers for the army! Cheers for the Carthusian monks! Cheers for freedom!) Yet again, the same scenario that had taken place at Saint-Michel de Frigolet was repeated. The judge ordered the monks to open their doors, calling out: “We are here in the name of the law!” A monk answered: “ There is no more law! ” The judge then ordered the police and the army to enter by force. The monks were found praying the Divine Office in the church. One by one, each was seized by two gendarmes. Their exile in Italy was about to begin.

These two events were not isolated ones but only two examples among many. When the proposal of separation between State and Churches was voted into law 1905, it was merely the result of many decades of anticlerical politics. The new law was yet, just another development, in a long, uninterrupted series of events that had taken place since 1789.

(d'après Jean Sévillia: Quand les catholiques étaient hors la loi)

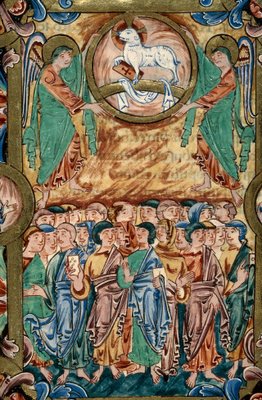

Eviction of the Carthusian Monks

(La Grande Chartreuse, avril 1903)

Historical Background

The French Revolution

1789 is a date that everyone knows because it affected not only France, but the entire world. We call it the French Revolution because it took place in France and was accomplished by Frenchmen but the end results impacted and changed the entire world. The word ‘revolution’ comes from Latin and means ‘a turn around’. The dictionary gives us the following definition: A revolution is a drastic change that usually occurs relatively quickly. It can be social, political or economic. In fact these three are interconnected.

The books of History usually date the French Revolution from 1789 to 1799 when Bonaparte took power and became First Consul. Ten years is a short time and thus is in agreement with the previous definition: a drastic change that usually occurs relatively quickly.

Yet, in reality it is more complex. A revolution can be a permanent process according to the theory of Trotsky. The purpose of a revolution is to change a society and this change must be total and radical. So, as long as there remain some elements of the previous society, the very society that the revolutionaries intend to change or annihilate, the process of revolution continues.

What was the purpose of the French Revolution? The idea for the revolution seemed to be a good one. The idea was to bring justice and equality to all the citizens of the country. The 1789 Declaration of Human Rights, inspired by the American Declaration of Independence, also, seemed to be good. What a beautiful ideal! But reality is different than ideals. It is usually admitted that the French Revolution was a Revolution by the people against the ruling classes, in particular, the King and the nobility.

The truth is that the Revolution was not popular and was carried out by the liberal aristocracy, a part of the bourgeoisie and the clergy influenced by the philosophy of Lights.

The Revolution is first a certain philosophy and conception of the world. It is the political realization of naturalism. We can define it as such: “

The Revolution is a set of doctrines and actions which want to replace the natural order of things and the natural order of societies wanted by the Creator in the civil, political and social institutions, by an organization elaborated by men themselves, and for that reason, in perpetual change.”

[1]

According to the revolutionaries themselves, the Revolution is universal and permanent:

- Jacques Alexis Thuriot de la Rozière (1753-1829), deputy in the Estates-General of 1789 and member of the National Convention said : “The Revolution is not only for France; we are accountable for it to the entirety of mankind.”

- Gracchus Babeuf (1760-1797), precursor of communism said: “The French Revolution is only the forerunner of a greater and more solemn Revolution which will be the last one.”

- More recently, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, former member of the Socialist Party and founder of the Mouvement des Citoyens (Movement of Citizens) said a few years ago while he was Minister of Defense: “The French Revolution is not really completed and probably will never be.”

The fact is that the Revolution didn’t end with Napoleon, who said of himself: “I am the Revolution!” The entire French political life in the XIX century was marked by the battle between the Revolution and the Counter-Revolution. Today this battle seems to have eased, but it is not finished.

[1] Revue “Permanences” n° 413-414

(Etats-Généraux, mai 1789)

The revolutionary ideology

It is fundamentally the dogmatic refusal of all notions of a pre-existing order which stands to men. Its underlying philosophy is Naturalism whose champion was Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It is not a coincidence that his book, le ‘Contrat Social’ (the Social Contract) is considered to be the founding text of the French Republic, even though Rousseau meant this work for small States. His model was Sparta.

Nature and reason became the warhorses of the Revolution and in their name, the old society had to change, or rather to disappear in order to make way for the new society which would be based upon a false notion of nature and reason. Now, there was an obstacle to pull down: Religion!

Religion is the enemy of the Revolution, because it proclaims the existence of an order above reason and nature. As such, it must be destroyed. The hatred of religion is a constant shared by all revolutionaries. In fact, contrary to a common opinion, the Revolution is religious in essence and political only by consequence. The Revolution can make the best of any political regime: Democracy, Monarchy, Socialist, Communist, Fascist or any other regime as long as it rejects the idea of a religious order.

Among all the Religions, one in particular is attacked by the Revolution: the Catholic Church. The hatred of God, of Jesus-Christ, of the Church and of the Christian order is a typical mark of the Revolution. The fact is that the ideas of the Revolution, inspired by the Philosophy of Light, contradict Catholic doctrine:

- liberty opposes order

- happiness opposes duty

- imprescriptible and sacred rights oppose obedience

- natural equality opposes hierarchy

- tolerance opposes the dogmas of the Church

Since the Catholic Church preaches order, duty, obedience, respect of hierarchy and teaches dogmas – without denying liberty, happiness, equality and tolerance – , She logically became the enemy of the Revolution. The war cry of the Revolution could be: Delenda est Ecclesia! (The Church must be destroyed)

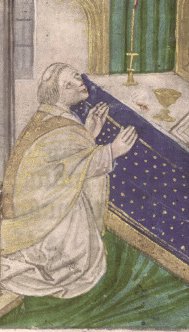

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)He inspired the French Revolution

To be continued...